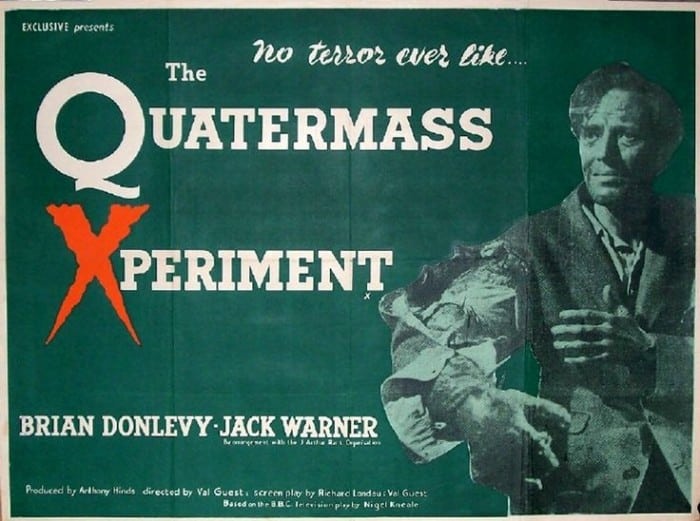

The Quatermass Xperiment (1955)

Directed by: Val Guest

Written by: Nigel Kneale, Richard H. Landau, Val Guest

Starring: Brian Donlevy, Jack Warner, Margia Dean, Richard Wordsworth

UK

AKA THE CREEPING UNKNOWN

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

RUNNING TIME: 81 min/ 77 min

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

The British Rocket Group, headed by Professor Bernard Quatermass, launches its first manned rocket into space. Shortly after, all contact is lost with the rocket and the three crew members. The rocket later returns to Earth, crashing into a field. Quatermass and his assistant Briscoe arrive at the scene, along with the emergency services. Opening the rocket’s access hatch, they find only Carroon inside; there is no sign of the other two crew members. Carroon appears to be in shock, only able to mouth the words “Help me”. He is taken to hospital while Quatermass and Briscoe investigate what happened to the rocket and its two missing crew. It quickly becomes evident that Carroon has been altered by something he encountered in space, and can absorb any living thing with which he comes in contact….

And so at last, we come to the first film that can be called ‘Hammer Horror’, though of course it’s just as much science fiction and its style is quite different from what would soon become the norm for Hammer horror films. It’s funny how time has changed, for what was once considered to be for ‘adults only’ is now apparently suitable for afternoon TV, though watching it again after a great many years, there are a few quite unsettling moments. The first major [though I have a distinct fondness for The Man From Planet X] British science fiction film that made a good attempt to beat the Americans at their own game, and a hugely influential work, The Quatermass Xperiment shows many signs of having been made on the cheap, but it actually hasn’t really dated very much, much of this being due to director Val Guest’s semi-documentary style handling [similar actually to the way Gordon Douglas made the giant ant movie Them!] which make it seem quite fresh and modern, and the limited employment of special effects also works in its favour, being a good example of how the mind can fill in the bits you don’t see, though it suffers a bit from being overly vague in places and not developing certain aspects in the way it could have done. It’s also notable for having the best truly sympathetic monster since Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein Monster, both frightening and pitiful. Its air of sophistication, realistic handling and terrific suspense combine to make The Quatermass Xperiment a minor classic of its kind.

It was adapted from an immensely popular six part TV series by Nigel Kneale. The BBC touted the scripts around a number of producers, but only Hammer were willing to make what had the potential of being an ‘X certificate [equivalent to ‘18′] production, even emphasising it in the title. Writer Richard Landau’s first draft Americanised many details and demoted Quatermass to doctor, but Guest removed some of these changes in his rewrite as well as 30 pages. As they would often do from now on, Hammer submitted the script to the BBFC so they wouldn’t end up shooting lots of footage that wouldn’t be used. The BBFC objected to overuse of the monster, which ended up being largely kept off-screen. The final screenplay heavily condensed the TV series, notably removing an extramarital affair between Judith Carroon and a scientist, and the monster retaining human feelings, even at the end where it originally killed itself. As with many of their previous films, it was co-produced with Robert L. Lippert who brought in a fading American star, here Brian Donlevy who was rarely sober on set. James Bernard, who became Hammer’s ‘star’ composer, wrote his first score for this film when the original composer fell ill. Timed to coincide with the TV showing of the Quatermass series Quatermass 2, the film went out on a double bill with either the short The Eric Winstone Band Show or the French caper classic Rififi, the latter becoming the most successful double bill release of 1955 in the UK. The first Hammer production to attract the attention of a major distributor in the US, United Artists distributed it, shorn of four minutes of dialogue, under the title The Creeping Unknown with The Black Sheep. It was so successful that UN offered to part-fund a sequel. A nine-year-old boy died of a ruptured artery at a cinema in during a showing of this double bill, the only known case of an audience member dying of fright while watching a horror film.

Unlike the TV series, the film jumps right in there with a very memorable opening scene of two young lovers about to have a nice roll in the hay being interrupted by a very phallic rocket which crashes in front of them [though the limited budget ensured that some of this occurs off-screen]. It’s possible to see this moment as symbolic of how Hammer were about to shake up the film world by bringing sexuality and gore to horror, though of course that wasn’t intended at the time. The early scenes carry an air of mystery about them, albeit of an almost documentary kind, Guest often employing a handheld camera [though unlike in most modern films it doesn’t shake very much – funny that] and overlapping dialogue, though what is especially interesting is how unsympathetic a ‘hero’ the callous, arrogant, irresponsible Quatermass is. The sole-surviving astronaut is no more than a scientific curiosity to him. He attempts to deny him hospital treatment because he will lose overall control. When he finally concedes, it’s only on the pretext that he will have exclusive access. He thinks normal coppers are too dumb to give any kind of evaluation. He shows no regard for the poor man’s wife. Kneale hated what Hammer did to the character, though it makes for an interesting dynamic. Our sympathies are soon much more with Carroon, the astronaut who is clearly infected by some alien organism, despite actor Richard Wordsworth looking impressively creepy with makeup man Phil Leakey accentuating the shadows cast by his eyebrows, nose, chin and cheekbone with a bright light, and a genuinely unnerving moment where, as scientists talk in the foreground, we see, through a window, Carroon get up off his bed and stumble towards his sleeping wife before collapsing.

After he eventually escapes and starts to kill, we get a touching bit, clearly inspired by Frankenstein, where he approaches a young girl [actually Jane Asher] who isn’t scared of him. Carroon rips the head off her doll but runs away when he realises what will happen it they touch. The film now becomes a more conventional monster on the loose story, except that we don’t now get a good look at the monster until the climax in Westminster Abbey. Not allowed to film there, they used models and paintings though you can’t really tell, while the creature, made from rubber, cow intestines and tripe, does look suitably revolting despite sporting a rather amusing octopus eye, added at the last moment to give it some emotion. The most chilling sequence though is earlier on when Carroon raids a zoo. Guest, who was adept in many genres, is never really known as a horror director but this scene really shows a mastery of it the way it cuts back and forth from the camera slowly tracking into buses to the animals being alarmed by something. Walter J. Harvey’s cinematography really is something else in this movie with its evocative and prevalent use of blacks all over the place, but it’s especially brilliant in this sequence. Of course we see hardly any of the killing, animal or human, though some shots of victims with their life sucked out are quite startling, and then there’s the bit where a new organism has formed and they’ve put a mouse in with it, which in the second shot is seen scrambling to get out of the cage while the thing advances towards it.

Overall The Quatermass Xperiment seems today like a fine example of how effective subtlety can still be, though of course it wasn’t especially subtle for the time at all. The Britishness of the whole thing gives us some rather charming moments like when, with all the agitation going on around him about the crashing rocket, Inspector Lomax get an assistant to bring in what turns out to be the adapter for his electric razor. Another funny moment is Thora Hird’s cameo as a drunken woman whom the police actually believe saw what she claims she saw for once. Generally though the film maintains a steely grip throughout, only stumbling sometimes when it leaves a few too many things unexplained, like when we view recorded footage of the three astronauts in the rocket. Though something clearly happens, we’re left none the wiser than we were before. Then there’s the thoroughly dislikeable Quatermass, Donlevy barking out his lines as if he needed to get them out as quickly as possible so he can have his next drink, though it’s possible that the writers intended him to be so unpleasant. The character is certainly a good representation of the reckless pursuit of something that is perceived as “progress” or “the greater good” at the expense of someone or something.

The standout performance is undoubtedly by Wordsworth, absolutely compelling and almost heartrending as a human being trying to fight off the thing that is taking over him. He’s especially effective in a car ride where his pained expressions convey all we need to know, but like all good monsters is still scary, stalking around with his raincoat and cactus arm hidden. I just wish there was more footage of Wordsworth, who is way down in the cast list, in this film. It’s the type of performance that is worthy of awards but is never considered because of the type of film it’s in. Another star of the film is Bernard’s icy score for strings and percussion. Quite unlike the typical horror/sci-fi film music of the time, and only consisting of 20 minutes of music, it’s very minimalist in its primary usage of one three note and one two note semi-tone, and is also notable for when music isn’t used. I guess what holds The Quatermass Xperiment back from being a genre masterpiece is its brevity – the film could really do with being at least 20 minutes longer to go deeper into things – but that wasn’t Hammer’s way, and in any case a great many films of wildly varying quality have played with and sometimes developed elements from this film including Lifeforce, The Incredible Melting Man, The Thing and both versions of The Fly. 1959’s First Man Into Space was a solid rehash, though the less said about the 2005 BBC remake, a disaster on nearly every level, the better. A seminal, trend setting work, The Quatermass Xperiment remains exciting, vivid, surprisingly modern and even timely. After all, the film ends with that idiot Quatermass stalking off saying he’s going to try again.

Rating:

Be the first to comment