With the release of his debut feature film, I sat down for an exclusive interview with writer and director. Randal Plunkett. to discuss the making of The Green Sea, his rewilding project in Ireland and cherished memories of Friday nights at the video store.

HCF: How would you describe The Green Sea?

Randal: It’s sort of an unusual one. I would class it as a personal journey through the surreal imagination to find forgiveness for oneself. That’s how I would describe it because the whole movie kind of deals with someone who has an ongoing trauma and is under the pressures of creativity, having to create for living and trying to repeat past successes, which is a very human reality. But it’s the fantasy world of the imagination which ends up curing her mental disease, so to speak. So I would say that it’s a personal journey into the realms of imagination to cure yourself of your ailments. It is a sort of surreal drama fundamentally which makes it a very unusual film because it’s not like a straight up drama and it’s not a straight up genre film either. It’s sort of a hybrid which sometimes makes it difficult to place. So I think some of the audience will probably go “ah, but it wasn’t genre enough” and some people go with “this is too genre for the drama people”, but I think there are people like me who will find a happy medium somewhere in there.

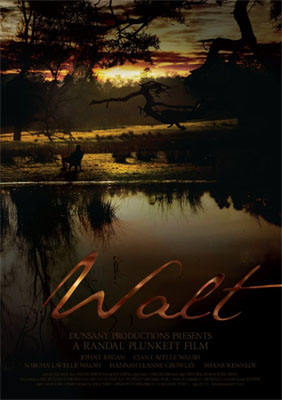

Previously you’d shot two short films, Walt and Out There. How did you come up with the story for this feature length film?

I have to admit that it’s somewhat biographical. I mean, Simone is basically a part of my own alter ego. Simone is heavy-metal loving, well, that’s me; a writer who can’t repeat some success, which I sort of had with my last short, but couldn’t really get the next one off the ground. She was a sort of stranger in a strange land where she doesn’t really feel at home and that’s very much where I’ve come from. Even the concept of the metaphor of the turtle; she sort of lives for her house. Her house is the thing that holds her to her past which is like me and my background, where I have to live in a place that is very much part of my identity. It is very much like the turtle’s shell. It’s as much part of the turtle as the head. So for me, it was very personal that way. Obviously I made her a woman which makes it far more interesting, especially from the dynamic of being so aggressive and abrasive. It’s usually not a typical Hollywood interpretation of a strong female character. She’s somewhat detestable for most of the film, but then at the same time has a bit of humanity in there. Especially by the end of the film, she has to sort of find that humanity and that’s sort of where I think the film is. But, yeah, it was very much a reaction to having gone through so many years trying to get things off the ground. I sort of felt you write what you know. Of course, I injected a lot of the fantastical because it is escapism that gives us so much solace, especially when life is difficult.

I’ve always been very fascinated by people whose interpretations of reality deal in the surreal. I was reading a lot of books by a writer called Murakami, who is a Japanese drama surrealist writer, and he writes these very unusual stories. I got very influenced by that. I mean it has all the characteristics of some of my favourite films and pieces of books, even art. Someone like The Collector, who was a direct reference to Czech film The Cremator, who looks very similar to him. Throw a bit of artwork in there and my steampunk glasses, and there you have a piece of my alter ego in the form of one of my favourite films.

How long was the process for writing the script and how did you find it different from the work on your short movies?

Well, the funny thing is that movie was gestating for a while. There was a couple of projects that I had that I couldn’t quite rope together. I decided to abandon a previous project or at least put it aside and pursue something that was more manageable as my first feature, because I wasn’t breaking the mould of trying to get things done. So I decided to smash these two or three ideas together and created something like that, which I think worked to a certain degree. Obviously, a lot of it had to be shaved up and turned in for the film.

There were certain concepts I was very interested in. The kind of bloody idea between the parents and the lost child was something I wanted to explore, and then the idea of a writer whose reality is her imagination, all those kind of ideas. I was just trying to rope it all together so it would sort of fit together as one kind of story. So, I mean, I did that within around nine months. All these other ideas were developing for several years before that. But I only wrote together for about nine months and we started filming at the end of 2018. We filmed the first half of the film and then we finished the rest of it in March of 2019. Post-production took until pretty much just before lockdown. We had a lot of problems such as the company that we were doing the post with closed down so I ended up having to do the post and finish everything here at my place. And we had problems with the editor as well. We had an editor who lives in Manchester called Chris Gill, who did 28 Days Later. He came to help me with the first bit of the movie and then he had to go, he got hauled away on another contract, and then I was left alone with a two and a half hour movie in black and white.

You’ve said how you’ve had to jump in and get your hands dirty in a lot of departments. So what did your role encompass, apart from being the director?

Well, I would have said fireman because I was putting out a hell of a lot of fires! But no, I mean, I think anyone making indie films is going to kind of have this already where you’re always doing something extra anyway. You’re always working. Only when you get into a more advanced stage of your career do you get to sort of be comfortable in one job. But when you’re kind of doing films for nothing, it’s like you are doing something. Even if you’re not getting credited for those things, you’re doing everything. You’re the producer. You’re making the food. You’re making sure that people have gas money. You’re also doing the accounts because that was some of the stuff we were doing. We were trying to make movies and I was sitting there doing accounts. There’s nothing worse than trying to do accounts in the middle of a movie especially when you’re looking at what’s being spent on what. It was such a learning experience and I’ll never forget it. I nearly quit filmmaking forever. But just like just like The Sopranos, “just when I think I’m out, they pull me back in“. I’m still here. I’m going to do another one, and that’s the problem. I’ll never get out. I’m a lifer.

The love of film is too strong?

Yeah. One day I was making this film and I nearly said to myself, “you know what? If I just fire everybody, I still have a bit of money. I could I could make it down to Virgin Records and just buy a lot of blu-rays and just spend the next two years of my life watching films, other people’s films and never having to suffer for it.” But luckily, I didn’t do that. I finished the movie… but it was tempting. [laughs]

I suppose it makes you appreciate other filmmakers’ efforts a lot more once you’ve gone through all that yourself. Whether people like a film or don’t like a film someone’s created, you can’t take away the effort that’s gone into making the story a reality.

You’re vulnerable. Let’s look at this from a linear perspective. This has been a massive dedication in my life for sure. Like we’re talking, what, nearly four years… it’s going to be five probably by the end. I mean, that’s a massive chunk of my life that has been spent with one idea, trying to get something that was perhaps very pure at the script stage, where you wanted to tell a story that may be about things that you are very touched by. These are pains and emotions and wants and you’re trying to tell a story. Of course, it’s going to evolve because the filmmaking process is also like childbirth. It’s very severe. It’s very painful. Then you get to editing and you’re miserable because it’s not what you wanted and it’s not what you expected. Then finally, somewhere along the line, you find the film. And that’s the thing. During the editing of this movie particularly, I couldn’t see the movie and I was panicking because one of the most dangerous things for a director is not being able to see the movie. That’s the one thing if people say what makes a good director, it’s a person who has a clear vision. If you don’t have a clear vision, you’re not a good director. Or, more importantly, this is not a good film for you, because if you lose sight of what you’re trying to say or what you’re trying to achieve, that’s the problem. Whether you give a lot of direction when you let the actors do your thing, as long as you know, at the end of it, you have to be able to see where it’s going. And there was a few times where I didn’t. I lost sight of it momentarily. Luckily, I was able to pull myself back together again. The chaos of film set and the chaos of trying to put together ideas, after a while, you kind of don’t see the movie anymore. You just see your own personal failures. It’s only then when you have to take a step back. This is what happened to me multiple times throughout the movie where I had to take a step back and I have to learn to love my mutant child that had like four legs, a tail and some fanged teeth when I wanted a beautiful blonde child with blue eyes, etc.. You learn to love it again and, more importantly, you rediscover what you were trying to say. That’s what happened to me. I rediscovered the things and the emotions I was trying to illustrate in my film.

I know a lot of people, once they finish a film, they don’t want to see it anymore. I went through that stage too but now it’s a sort of celebration of some of the things that I went through and some of the things that I tried to do. Whether I succeed and whether people find something in it, that’s not really the nature of what it’s done for. I’ve expressed what I wanted to express and I hope people will find something in it for themselves because that’s what what happens to me when I watch films; I get something from them. I feel an idea or an emotion that perhaps was being expressed by the the director and that’s what kind of brings me to certain kinds of films. Not all of them are necessarily perfect films but I find something. I mean, take Hellraiser, for example. I love Hellraiser, but it’s not a perfect film, however it has something there that attracts me to it and that’s why, I suppose, I like some trashy movies as well. I mean, those childhood movies particularly have that because you have an emotional connection to them and that’s why you watch them twenty years later even though they’re like absolute schlock. You still find that connection. I have that for some of those crappy Hulk Hogan movies, I think.

The film takes you on such an emotional journey of Simone’s character. I thought she was really well-written character. I find it very rare to see good female characters on film, especially main characters. Some male writers write female characters as very one dimensional. But with Simone, she was human; she had layers and depth to her character. You could see she had goodness in her heart underneath the anger and trauma.

It’s interesting to see how people have interpreted it, because I have a couple of people, particularly parents, who absolutely hate her by the end of the film, can’t stand her, but it’s an extreme reaction. Even some of the worst people, they have their moments, you know. I was very influenced by a TV show called Oz which was about a prison, and, of course, you have the worst people ever all in one place. Although they were absolute monsters, each one of the characters had a piece of humanity and they were often products of their environment.

I will not take full credit for Simone because a lot of that was also Katie, who, let’s be honest, made this film her own. I often find that Katie is not really represented well in her abilities as an actor. And what I mean by that is I often think that people don’t actually consider her as good of an actor as she actually is. I really wanted to make something with Katie that I could really showcase the ability that I know for a fact that she has, but also something that was a bit like her Monster, you know what I mean, with Charlize Theron? I wanted to make her so we stayed away from trying to make her very attractive in the movie. I mean, she’s wearing her pyjamas half the time and she’s got that grotty t shirt… We got local label, Invictus Records, to help us and they gave us a lot of their best death metal t shirts.

I wondered if they were all yours Randal? [laughs]

No, they were actually loving donations from from various death metal bands from all over the place, nut she kind of she kind of dresses a bit like me and even ironically, as a sort of nod to myself. I even have the same jacket as the jacket Kid wears (Hazel Doupe). Without giving any spoilers away, so many so much of those characters have so many parallels in their own spirits, you know. That’s the thing that makes writing an interesting female character very interesting. I was very tempted at first to try a male character, because I know I know what it’s like to be a male, but I also found that it’s very limiting and it’s been done quite a bit. To write a character like Simone who’s so abrasive, who has no reason for any sympathy, but yet you feel terrible for giving her a bit of sympathy, that’s something I wanted to challenge the audience with because it is very uncomfortable to accept all the bad things that she’s done and forgive her. Worse yet, to even identify with her. You kind of almost feel dirty by doing it. That, for me, is not something that’s done because it’s risky and it’s for a good reason it’s not done because you run the risk of alienating your viewership, but I still want to do that anyway. I think that’s the problem with a lot of films, the way the market in the industry has worked. We’re very scared to take any chances because we’re worried about people not liking it. We’re worried about people not making any money out of it so there’s very few opportunities in making films nowadays to really challenge by taking things that are necessarily unpopular or dangerous. That, for me, was what The Green Sea was. I took somebody who, let’s be honest, without giving spoilers away, she’s harsh and she’s hard to like at times, but at the same time, when the emotions are there… I mean, there were scenes when she was shooting that I myself felt like this is some deep stuff, I feel bad for her.? I won’t I won’t name the scenes, but I think you can probably guess which ones those were, and that’s for me was sort of a special part of the story. Yet it still has a bit of positivity to it because there’s still the possibility of salvation. It’s not somebody giving you salvation, it’s you earning your salvation.

And sometimes you can be your own worst enemy

Yeah, well, I mean, that’s her, isn’t it? She’s a fuck up. She ruins her own life, it’s nobody’s fault, but that’s what’s interesting when you have people who fail and are not like are flawed by design. Someone who doesn’t have confidence so they they hide behind a mask of being abrasive or drinking or like being violent. Often those people are the people who are in the most pain and they hide behind these things, and she’s a perfect example, She’s sort of a coward for most of the movie, hiding behind her harsh exterior. She’s nice to nobody, you know, but that’s because she’s vulnerable. That’s why there’s the interesting aspect of the writing and her being a writer, because she creates her narratives. The only time she feels solace is out in the calmness of the wild. If you look at how we designed the house… it was completely designed from scratch, even the colour. I mean, who paints their house black? My mother said, “well, we could paint the house next to black” – anthracite is what we called it. The joke of the film set was we called it the chocolate brownie house. That was a gentle nod to Anton Le Vey, the famous Satanic Church guy, who had a black house. Even if you look at that house itself, it’s very claustrophobic. Even to film in that tiny, little house was an experience. If you look at some of the shots, there’s all these antlers and the way the shadows work kind of keep that claustrophobia in. You don’t get that on the outside because everything is peaceful on the outside, even though it’s grim looking in because it’s winter in Ireland. But there’s the elegance of the trees. Even the way the camera moves is a bit softer than in the house, which is just dark, shadowy and dusty with antlers everywhere. Everything in her imagination is there on the walls. Even the corridors have got the paintings of the beach and she’s got the antlers on her neck. Everything there is is a metaphor.

I agree that the setting of the house is quite claustrophobic and it feels like whenever she feels threatened, she recoils inside herself and runs back to the house. The only time she seems to just relax is when she goes on those walks. Were those scenes shot your estate?

Yeah. That’s all the nature reserve that I work on again. I have a vested interest in the environment. You know my career a little bit and you’ve kind of seen that evolution. There’s always that kind of nature theme in my work. I always try to put that in, even going back to my first day. If you look at my early short, Out There, I mean, what was the main character about there? He was a kind of cowardly man who didn’t really love his girlfriend. He let her die. I kind of like these characters who are not perfect people. They’re flawed. They suffer from from arrogance. They are so full of flaws, but often they’re scared and that’s the problem for Simone, just like it was for the lead character Conor Marren who played the guy in Out There. They both suffer from very similar stuff. They’re running from things. They’re hiding. It’s a common theme throughout my work and I tend to just do the same thing over and over again in different colours. [laughs]

I thought the exploration of Simone’s character was exceptional. When you were casting for the roles, especially for Simone and the Kid, how did that go about? Did you have people in mind or did you just hold auditions?

Well, I was I was having breakfast with Katie and I just pitched the idea. The film that I was working on was being delayed, so I said, “well, what if I could do something a bit more minimalist, kind of a character-driven film, not a big action movie or big horror. What if we could just do a sort of offbeat drama? Would you be interested to do it – like a real actor’s role?” I can’t remember exactly how she said it, because she’s way cooler than I am. So she turned to me and just said, “Randal, I’ll be there.” So she was already, from day one, the person who was going to be Simone.

A lot of Simone’s characteristics were written but I would say they were improved greatly by Katie because she took the foundation of what it was and she made it her own. As for Hazel (Doupe), who plays the Kid, she had a tougher time because the film was about Katie, and Hazel’s character had to reflect from her past and be a sort of mirror. So I needed somebody who was striking to look at… I don’t know if you noticed that we filmed a lot of very intimate shots of Katie’s face because she has very striking eyes. It’s her eyes is what gives it that depth of distance in her character, I find, and I needed to replicate that with the opposing character as well. So we cast Hazel, who has the same very striking appearance of these very big eyes with a lot of depth to them. So I had to kind of find people who could both do the same thing. Hazel was an actress who I’ve been following since I think she was about 12. I saw her do some stuff at a time because a friend of mine worked with her and he said, “you have to look at this girl”, and I saw her. I’ve been cooking up an idea for her for years and finally, this was the opportunity. I gave her a call and said, “yeah, I’d love to work with you.” But she got behind the script and, of course, was very excited to work with Katie.

I’d seen that Hazel had been in a couple of other roles where she’d been tipped to be the next rising star in Ireland

I still think it’s going to happen because she’s she’s got a lot of talent and it’s it’s hard to tell in The Green Sea because she’s so minimalist, but that’s very much her power. She’s able to do a lot without doing very much. The only thing I was worried about when I started was, is Katie going to be too much? Is she going to show up the other actors? Because one of the biggest problems with casting is not about just finding the best actor. You have to find the best actor who’s not going to showcase the lesser actors or the smaller actors and make them look like the weak link. It’s like making soup. You can put a lot of salt in it but if you oversalt it, it tastes like shit. Katie is a very flavorful actress and you need those other ingredients otherwise it ain’t soup. It’s just an ingredient. So for me, it was trying to find the right balance. I think I was very lucky because all the actors seemed to fit really well because the husband, played by Zeb Moore, was also the same. Again, we’re talking about people who have not worked on the same level as Katie, being able to hold the screen with Katie. That was, for me, very, very challenging but I was lucky enough that we casted the film really well and they were all able to hold it. Luckily, because it could have been a disaster otherwise.

Lots of horror fans will recognise Katie from Ginger Snaps and American Mary, amongst others, but Simone was such a different role for her. I know you’ve said previously that people might not appreciate the range of her performing talents and I think this film was perfect to showcase her skills because really this is Simone’s story. Most of the film hinges upon her performance and she just brought it to the table. It’s interesting to hear that Katie added substantially to the character from how you wrote it.

Very much so. I got to be honest with you, There were things that I was discovering about the character that I created from Katie who was able to analyse the character even better than I could, and I was the one creating it. But that’s that’s the benefit about having someone like Katie. I always believed it and now I know for a fact, Katie is one of the best actors of her generation. Unfortunately, like I said, she’s not been recognised as that, but I certainly feel that this movie has done her a lot of justice. I think she really showcased that she’s a really top actress and she can do anything.

Working with Katie was very impressive because it wasn’t just that she was an actress and turned it off and on – she was someone who lived that character during the production. There were points where I wasn’t sure if I was talking to Simone or I was talking to Katie. There were one or two moments when Katie would just turn to me and give me that Simone look and that Simone kind of response. I just kind of backed away a little bit because I wasn’t sure if she wasn’t going to hit me, you know, and that’s where we were at. She brought that level of intensity to it, particularly the scene where she’s against her husband in the kitchen. She was terrifying in that scene. Myself and the rest of the crew were terrified because she would do this thing where she kept spinning around and I didn’t understand it. We were too scared to ask what she was doing. She would just be spinning in circles. You know when people get all rigged up for a fight? That’s what it looked like. It was a very difficult scene to shoot as well because we had very little space in that kitchen. As you can see, it’s tiny. It was really hard to get the sound and the camera and the choreography all in that one little kitchen and not kill anybody, literally, so we had to shoot that scene over and over again and she was getting more and more revved up every time. It’s only about halfway through that I kind of pegged what she was doing. She finally explained it to me. She’s like, “oh, yeah, well, if I spin around, I’ll get dizzy. And then I don’t have to pretend to be drunk because I just have to try not to fall.” I was like, “that’s why they pay you the big bucks and why I have so much to learn still” because it was brilliant. I tell everybody that story because it’s one of my best Katie moments.

Did you utilise any skills you learned from your short film work that you’ve applied to your feature film?

So I’ve always been a big fan of movement and we wanted to try and create something. It was very difficult during this film because we were so tied to the scale but there’s a lot of shots that we used that were very similar. There’s a lot of stuff on the beach where we used a very long telephoto lens. We did this in Out There as well. I call it ‘the nature shot’, where you use a long telephoto lens and get up close to the subject and reduce the depth of field, creating a shot you typically see in National Geographic. We used it for when we were looking at the dragon boat and stuff like that. I was very keen on that. We use them and a Nikon lens, which was used in the X-Files – a bit of trivia there for you. I love the X-Files and because I’m a big nerd I had to use the X-Files lens. Not that we needed to use it, but we had to.

I tried to build on what I had the last time because I mean, if you look at Out There and you look at this movie, you can see that it’s probably made by the same person. There’s a lot of this kind of transitioning into memory or transitioning into alternative realities. Again, it’s sort of unnatural because I would argue that both films have an element of the unnatural. I mean, if you go back to Out There and you look at the whole kind of way the guy goes into the house and there’s this almost injection of horror, and then you look at The Green Sea and there’s a very similar aspect. There’s a lot of horror elements put into it, like the factory and the guys and a lot of the same cast members as well. Incidentally, the drunk driver who’s in The Green Sea is the actor from Out There. So I used a lot of that sort of stuff.

Of course, I tried to do something because with Out There, everything was very lush and healthy and green. What was boiling under the surface was sort of behind the beauty. Then with this, I kind of tried to do the other way around where everything is very grim looking and very dark, where there’s a sort of sense of beauty underneath. So I sort of inverted it. You see that a bit with the contradiction between the darkness of the house and these beautiful shots of outdoors. If you look at the way we coloured the films, both films, the grades don’t look natural. That’s part of where I wanted to go with the movie, because even that scene where they walk through the woods together, you see that the sky doesn’t look natural but that’s because how much of it is our interpretation of our own reality? I kind of wanted deliberately to do that. Even the beach, it almost looks too much. We kind of went for this very unusual look. In any of the films I’ve done, I’ve never tried to keep the kind of colour tones very natural. I always wanted a sort of slightly unnatural feel to the scenes. That, for me, is something that is personally to my taste. I really like it because it feels fantastical. I suppose I built on what I did with Out There with that, and, of course, I’ve used a lot of the same people. The guy who did the music has worked with me since the beginning.

Obviously the evolution of the music was quite a buildup as well. This is very music driven. There’s a lot of sound and a lot of music in this film. We created a lot of different kind of soundscapes, particularly if you hear the stuff on the beach with the glass-sounds. I tried to build a lot more atmosphere, so there was a lot of that because, even with Out There, there wasn’t a huge amount of dialogue; it was a lot of movement, us tracking people through the wilderness. It was much the same in The Green Sea as well. I repeated a lot of the same things, again, with a bit more refinement, I would argue.

You mentioned you was working in different departments and one of those was effects. Can you tell us a bit more about that and what sort of practical FX were used?

There was a lot of makeup. Katie had all these tattoos and stuff and, without giving hints, we had to work on the violent aspects too, the blood and all that, so there was a lot of practical. There was a lot of digital effects as well; a lot of removals. There was a lot of treatment to the sky and other little bits and pieces like that. A lot of it involved putting images onto glasses and reflections. The Collector was always something. I wanted to create a character with him that was sort of a dead person. The reason why the the glasses were so circular was it kind of implied he didn’t really have a soul. If you look at the movie The Cremator and look at the main character, the cremator, you’ll see that he’s got almost the same clothes. There’s a very famous painting where it’s a guy with a similar outfit with the apple over the face. It was a mashup between those two images for me that created that character. He’s sort of like the matchstick man of the film, you know what I mean? He’s very minimalist in his interpretation of it. He’s almost like a David Lynch character. I grew up with a lot of David Lynch’s films, and it’s not so much a homage as it was, I suppose, an influence. I love that element. I mean, it shifts genres in the middle, and I’ve always really liked that the Japanese have done that a lot in films. If you look at films like Audition and where you got these kind of slow burner movies. Another great favourite of mine would have been Hosu (House) by the Japanese where they were pretty much bending genres throughout the entire movie. I mean, every scene was changing the aesthetics. You can never get away with that in Western cinema. We’re very conservative with those things. I am very interested in Japanese culture and history and cinema. Fr me, I always found their sensibility to being able to push the envelope in terms of genre, in terms of typical writing, very interesting. It’s risky because, like I said, Western films just don’t do that generally for a lot of reasons. It’s a cultural thing. I tried to do that a little bit with this as well so you do have that shift of genre in the middle. Then again, it’s very much in keeping with what I was trying to go for, which was, you know, the mind cracking of somebody.

The Collector is such a striking character

I don’t know if you noticed. I mean, there’s a scene where he’s there and he leaves the room and then the whole thing changes. The lighting changes, the colours change. When she’s in the room and this is really interesting, everything’s kind of like an artificial blue. The amount of noise and the amount of sounds going on in that scene is absolutely nuts. If you ever get a chance to watch it in 5.1, you should. I’m so proud of some of the stuff we worked on in that scene because there’s sounds and movements like footsteps running across the ceiling and all this kind of stuff. It actually is like when your mind cracks. It reminds me of that film that Christopher Nolan made where he gets stuck between the back of the walls and you can see the realities of old memories and stuff. It’s almost like that where you’ve broken out of the human consciousness, and that’s the thing with the colours. Everybody’s almost like a bluish twinge and then the moment he walks out of the room, all the sound disappears and everything just goes back to normal again. It’s literally that. It’s almost like a cloud gets lifted.

There’s lots of like whispers and things that I noticed throughout the film. Although I didn’t listen to it in 5.1, I could tell that a lot of effort had been put into the sound – it’s just so layered, so it’d be great to experience that.

It’s being released as 5.1 on digital download so if you do have a 5.1 system, you can at least experience a taste of what I was trying to do. Like I said, I’m big into hi fi so how sound works is very important. It’s one of the most important aspects to film for me. A lot of directors will focus a lot on the picture but, for me, sound was crucial. I’m lucky I had a very tough sound guy named Darius McGann who was very keen to get the best sound all the time. He was making sure that we were getting lots of coverage and sounds and the footsteps. All of this stuff, even part of it, was incorporated in elements where you don’t really hear it, but things are there just enough that you can register that something’s there but you don’t know. It’s same with the children’s voices. It was also like the Pied Piper, all the guys, the sort of boatmen of the River Styx, with the sound of the children. That’s what I really liked about it is that it’s got a lot of mysticism to it. For me, it’s kind of fun to try something like that.

In regards to the costumes in the film, I love the jacket that Hazel was wearing, that denim jacket with sheepskin-type lining. I really like the fashion sense of the female characters.

Katie’s stuff is very funny in that. You’re used to seeing her in all these skimpy little outfits but in the movie she’s not sexy at all.

She’s so layered up, isn’t she? She’s on the beach, wearing multiple layers complete with a massive scarf.

What you don’t see in those scenes is how cold it was. There was like gale force wind coming at us. I was dying like literally. Your skin got that cold burn what you get from the wind. It was rough. They were trying to do that scene without blinking, you know what I mean? It was a full blown wind storm. That was the first day that we arrived together. None of them had met each other before. They met each other like ten minutes before that scene where they’re all hugging it out on the beach. And I was like, “hey, this is Hazel. This is Katharine, by the way. Now you’re going to meet and pretend like you’ve been through all this shit together”.

So it wasn’t shot chronologically?

No, not at all. The stuff that was all the dream sequences was shot in March the following year. Katie wasn’t even there for any of that stuff. The problem is, I had to reconstruct this whole film because we ended up shooting and 30 percent of what we needed to shoot with Katie was never shot. So we had to rework the film and I had to cut so many of my favourite scenes out of this film. I kind of wanted something that was a bit deeper and I had made a movie that was a bit deep. The problem was the pacing was wrong. When I cut this version, I cut a lot of the depth out of it but the pacing was better. I showed it to a few people and almost everybody agreed that this version was better than the one that was a bit slower. It was just a bit too long and was just shy of two hours. I’m like, “nobody’s going to sit there and watch two hours of that shit”. You’re trying to jump through all these hoops and all you want to do is tell an original story. That’s why my hat comes off to anyone who makes a movie and finishes it, because actually, whether it’s successful or not, it is such a challenge to do it.

You’ve made your main character Simone a former musician who had some reasonable success. Now she’s a novelist, again, with prior success who’s trying to repeat that with her next project. That’s two industries where you are sometimes judged on the work you did last, especially if it was a hit. How did you decide that her being an author was going to be the route that you’d take for that character?

There was a guy who I was very inspired by, and he was a musician called Scott Conner and his stage name is Xasthur. I think that’s how you pronounce it. He’s a one man band who’s very dark. So I actually connected with him because I was considering hiring him for a movie to do the soundtrack, but because of scheduling issues, he couldn’t commit to the film. He didn’t have the abilities to do a movie and had never done a movie before. He was a sort of a reclusive soul who would write this very dark, very melancholic, extreme music. He was self-taught. He would just teach himself how to use all these instruments. I watched the feature on him and things that he said really inspired me. Some of the things that he said ended up in the film as an inspiration because that character of being rather brilliant creatively, but having this sort of alienation of people is something that I’ve seen in my experience with musicians. That sort of personality complements a character like Simone so there was a lot of inspiration taken from him. It’s the idea that music doesn’t really give you much. You have to end up putting a lot into it. It’s very similar to filmmaking, actually, for the work you put in, you don’t get much out of it a lot of the time. You get a very short taste of success, perhaps, if you’re lucky, and if you’re not, you lose your house, but it’s that need to create.

I think with Simone, the idea of being able to hide behind your own ideas and novel writing is something that’s very interesting because it doesn’t need a band. You can do it alone by yourself. It is something that is very personal because even in music there’s a certain amount of interpretation. When you create something like a book or something, you’re telling a story in a very delicate, very detailed way, which the music itself is the detail. When it comes to music, it’s poetry and music but with writing, you can really elaborate in a heavy amount of density what you’re trying to express, and that’s what I feel. I think creatives tend to be very multifaceted, multi-able so I felt that she was someone who later found some sort of success in something that she perhaps wasn’t geared towards. Even in my own career, I found myself trying to be a filmmaker and I found that I probably got more famous from doing the wildlife stuff than I did doing the film stuff. So for me, it’s much the same thing. You still want to do both but people will often look at you and say “that’s what you’re really good at” or “that’s what you’re known for”. I think that was my nod to that as well.

Can you tell us a bit more about your work with the rewilding project you’re doing?

I live in an old Norman estate and I was born into privilege. A few years ago, while I was creating, I suppose in my mind, I was creating the story for one of the scripts I was writing, I became fascinated with the environment and what happens to it when people disappear. To cut a long story short, I kind of got a taste for it. It wasn’t even called rewilding back then because that was a term that became fashionable much later. At the time, I was just thinking of nature conservation, which is about as unsexy as you can get in terms of a word. Rewilding is way sexier. But the thing is I found it. I suppose I could say I found it or it found me and I found that I had a lot of power and a lot of abilities to be able to do something about it because I’m fascinated by the wild. The only problem is I don’t have any wild because nothing’s wild anymore. Everything’s been destroyed. Everything is being developed.

I often find that people overlook the environment and they talk about culture and history all the time and language, but the land is as much part of our culture as our language and often that is forgotten. Our wildlife is as much part of our country as our national identity but we forget that too. So I kind of became obsessed with that idea. Particularly, I wanted to preserve what was here, what was wild, and give the environment a chance. Over time, as I began to see more and more changes to my place, I realised that this was a very important thing that I was doing here and it was necessary. Like I said, I’ve always been fascinated by the environment. It’s always been a theme in my film. So I suppose really, I guess the environment developed into a bigger thing in my life. As time went on, one part of my life complemented the other. So I suppose with filmmaking, that made me take notice of the environment and, as a result, the environment became a major part of my life and I fought to preserve it.

Dunsany was the first rewilding project in Ireland. It’s the biggest in Ireland with 750 acres of rewilded area, which is massive. We’ve seen so many animals return. Species that have been gone for hundreds of years are now back and every year something’s happening. I decided to draw a line in the sand and say, “bees are dying? Fine, we’ll do something about it”. Not to sound very Trump about everything because he talks a bit like that. Sometimes I laugh a bit about it because he’s from New York and I was born in New York and maybe I’ve got a bit of Trump on me when I was born there. It’s that that attitude what was needed to get things done. “We have a problem with bees? Let’s try and sort that problem out”. “How do we fix that?” “Well, we need an environment that’s not full of poison.” “Well. OK, I’ll do that. How do I do that? Well, I’ll put loads of beehives in here.” “Oh, we’re running out of owls because they’re all dying because there’s nowhere for them to go. Well, I’ll put up owl boxes”, and it was just making a list and going “right, what can I do about that?” and not waiting for anyone to tap me on the shoulder. Not waiting for a government to give me a little bit of money. I just said, “no, this is a problem that needs to be done today”. I got, what, 30, 35 years, maybe at best, to live? I better make tracks and hurry up, because if I don’t do it, who else is going to do it. I’m in a position where I can actually make a serious impact because most people maybe have a small garden or they live in an apartment. They can’t do that much. They can do a bit better. They can recycle, they can maybe put some flowers on their windowsill but I actually have an ability to make a serious change.

I’ve always been a big believer of walking the line and living by example. Not that I think everybody should be like me, but I just decided that this is something I believed in so I was going to do something about it and that’s it. It became a major part of my life. I would even say it’s overshadowed my career a bit, but I don’t see them as separate. I think both have their merits. I think I have more abilities in one than the other. I’ll let you decide which one that might be but the truth of the matter is, I think the environment is everybody’s problem and filmmaking is something that’s personal for me. It’s what I’m able to do. It’s something I want to do and both make me very happy. Just like Simone in this movie, you find the way to make yourself happy with yourself whether you have to have an epiphany like it happens in the film. That was very much how it was with me as well. I found a moment where I had an epiphany and I was like, “well, this is more important or this”. That’s what influenced me to do it. I decided now I’m going to do it. I’m going to be worse than that. I’m going to sing it from the top of all the trees and say this is what we need to do so I did.

Every day we do something. I always considered life was a bit like a war. You’ve got to do micro disciplines to win a war. You need to do minor attacks. Every action matters. So I started doing things, little things, you know, patrolling, stopping hunting from going on, stopping poaching, putting myself in danger but it’s those actions that I believe earn you a place that you can actually say, “yeah, I did all I can do”. But you have to get off the couch. It takes the discipline of doing it a little bit every day for you to reach the point where the image becomes clearer. You’re way more controlled and satisfied with the things and decisions you make, because you’ve created yourself through this discipline. That’s how I did it with the environment, and that’s how I treat my creative process as well.

Have you considered bringing your filmmaking skills and your rewilding project together to create a documentary on the work you’re doing?

I have never been good at documentary since I talk enough for the whole of Ireland. Funnily enough, there’s a company called Off the Fence who recently did a documentary called My Octopus Teacher. It won an Oscar this year and their next documentary is about Dunsany and what I’m doing. So I don’t need to make the documentary. I’ll just be the star of it. [laughs]

I like to often just jokingly say that I’m the David Attenborough of my county and I sit there and say “look at all these holes”. [laughs] The irony is that I’m not a scientist. When I started this, I was ignorant as hell. I didn’t know what anything was. I didn’t know what the difference between this tree or that tree was. Like with all those micro disciplines, you learn a little bit, you educate, you listen, you practice and over time it changes how you look at things. Now I find myself a lot secure in my own self, which is ironic because I’m a filmmaker so I’m insecure by nature. That’s why we do it but at the same time I get a lot of solace out of it. Just like Katie in this movie, she goes and walks amongst the trees. That’s exactly how I feel. That’s what I mean when I say however this movie is interpreted by people, it doesn’t really matter because I found my story, and that was very important for me because I found again a bit of solace in some of my creativity and it had injected some of the elements that I’m fascinated by and that I’m interested in. That, I think, is what we’re all trying to find. We’re all trying to find our own truth.

This film wasn’t easy and it cost me a lot. I’ve had friends who died. My mother died during the making of this film. I had three friends die and they were all in the film and were people who had been with me for a long time. No great journey goes without drawbacks and casualties, you know and I feel that it was a great journey. I feel that it represents something that I tried to be honest with and I think that’s where the sort of philosophical concept of the whole movie comes back in. I’m very proud of the people who helped me make it because it was something so personal for me. Some people will not like this film, and that’s fine, they can slam it on IMDB and give it a zero and that’s OK or some people may like it. That’s the interesting thing for me now is how will people interpret it? Because we didn’t do a festival so I don’t actually know how people are going to like it.

So the film’s release on digital is the first time it’s been put out to the public?

The cast and crew haven’t even seen it prior to release, you know what I mean? So I don’t even know how people take it, because when I look at it, I see something else. The casual viewer, maybe they’ll interpret it better than I can because I’m too close. But for me, there’s The Green Sea. It’s a story that only I’m ever going to really understand. Everything else beyond that time is going to be an interpretation. It’s like David Lynch’s films. I’m sure David Lynch sits there and goes, “well, that’s because of this.” But he’s the only guy understanding his own movies. We all look at in all and it’s the same with people like Buñuel as well. I mean, those are pioneers who made movies for themselves and people found something in them. I think for me, that’s what I aspire to be – someone who can make something that I feel personally connected to. And maybe somebody finds something relevant in it, you know.

I’m so curious to see what the person who comes off the street sits down and watch that film is really going to get out of because I actually don’t know. They could get nothing out of it, in which case I failed terribly as a filmmaker. But, you know, maybe it’ll entertain somebody and they’ll steal it or they’ll buy it or rent it… we’ll go with rent. Please don’t steal it.

Yeah, please don’t. I suppose that’s always the risk with digital these days.

People who buy DVDs, there’s an investment made in terms of you decided that you’re going to take this thing, you’re going to bring it home, you’re going to live with it for a while. Even when you even want to put it on, you have to go through a whole process. There’s a certain amount of decision made when you’re going to watch a movie. The problem is when you steal a movie and watch it, you’re probably watching it in a terrible quality as well, which is even worse. I mean, there’s no desire there, you’re just consuming.

I’m still one of those guys who likes to buy a film because I like to hold it. I like to take it out. I don’t care too much about the special steelbook edition. That doesn’t interest me at all. My only interest is the closest thing to the quality, the fidelity of it. That’s what interests me. So I want the perfect sound. I want the perfect picture, the highest level of grain. That’s what I want. That’s what I go for. I couldn’t care less if it comes in a slipcase, you know what I mean? As long as I get the closest thing to what was intended. But that’s me and that’s why I’m into Hi-Fi and stuff like that and hat’s why I spent ages messing with cables and and playing with conditioners and swapping fuses out. I’m that guy. Me and the middle aged men. [laughs] But that’s an obsessive part of my personality. I don’t see blu-rays and stuff like that completely disappearing because there is there is an audience who want that. They might not be the mainstream audience. Arrow’s doing quite well, from what I can see.

Second Sight as well. They’re releasing bumper editions with plenty of special features and documentaries on them. I think, especially with the horror and sci-fi genre, people are into that sort of thing. They love collector’s editions chock full of behind the scenes details. I don’t think that will ever die out, will it?

No. Like I said, people just want to get closer to those movies because they identify with them. Going from 1080p to 4k just brings them that much closer to the movie. I don’t think that’s going to disappear. You can probably stream 4k on Netflix, but it doesn’t look the same. Certainly doesn’t look better because I mean I’ve compared the 4k Blu ray to some of the 4k streams. It ain’t the same, but I’m a nerd. I sit there measuring things and looking looking at stuff. You know, I’m that guy on bluray.com looking at “does the German edition look better than the British edition or American edition?”, and, “is there more moire in the American edition?” I’m that guy.

I’m more of the opposite in terms of I don’t like anything super high definition. Especially the horror movies from way back when they were released on VHS. I don’t want it super cleaned up. I want it to be grainy and VHS quality, that grimy, dirty feel.

You’re a similar generation to me. You remember, that’s how we grew up, with the video store. It was a personal thing. I remember the video store and it was the best times. Kids today, they have it on Netflix but there’s no enjoyment there compared to what happened when I went to the video store on a Friday night. You’d sit there and you’d look at the boxes and you’d be like, “oh, what’s that?” And you take it out and you’re like, “Oh, I’m not 18”. And “can I try and get this videotape?” And you try it on with the guy behind the desk, the teenager with the spots. “I’m 18. I left my ID at home”, and then you’d blag it. Sometimes you’d win, sometimes you wouldn’t. Then you’d get this VHS tape home and the movie was just terrible. You get that fizzing sound in the background, but that was also the joy of the chase, wasn’t it, to get the movie.

Absolutely. The video art was a lot better than what you get nowadays, I’d say.

It’s so much better. Oh my God. Especially some of the more cult movies like the action films at the time and the kung fu movies. I respect people like Arrow because they’re at least trying to replicate a lot of that stuff in a different aesthetic but it’s still very much like what I remember. Back when I was growing up, there was a lot of martial arts movies – they were a big thing in the early nineties, those big kind of like B-movies, like Best of the Best. It was always so dark. You always get these like really dark Asian films where everybody’s like smashing through restaurants or whatever, karate kicking it. Eric Roberts was another one. You’d see Eric Roberts in a lot of movies and he was young and handsome. You had all the other ones, like the Steven Seagal ones and that crazy soundtrack that you get. I loved all that. Funny enough, I was chatting to Steven Seagal right before the lockdown because he was coming to Ireland. I was thinking, like, I’m flying him over to my place and see if I can get him in a movie, because he was a hero of mine when I was a kid. I loved his stuff. I loved all those kinds of movies.

I love the Jean-Claude Van Damme stuff like Bloodsport

There was all these cool names like Death Warrant. I mean, it was just great. I remember watching that stuff in the cinema and there was nothing cooler at my age than watching a Jean-Claude Van Damme movie in the cinema. In America, they didn’t care about the age unlike the UK where everybody was like, “you cannot go and watch it”. In America, if it was rated R, no problem. I went with my sister, sat there and I watched Death Warrant in the cinema with my popcorn and coke and I even got to play arcade games. It was awesome. Kids today have nothing, man. They can play with their phones but that’s shit.

Especially since lockdown’s happened, a lot of releases are just coming out on the streaming channels, sometimes at the same time as cinema or it’s even bypassing the cinema. It’s certainly changed a lot. Like you say, I hope physical media doesn’t die. I don’t think it will. I think the collectors will keep the medium alive.

They will keep it alive. It’ll probably become very niche. But then again, I don’t think anyone expected vinyl to receive such a resurgence either, so…

Yeah, that’s done well, I mean, HMV was on its knees and then got bought out by Sunrise Records who I think had made a big impact in North America with vinyl, and vinyl just took off again hasn’t it?

It’s amazing. We might start seeing film prints becoming a thing, you know, because that’s the analog system. Are people going to start buying projectors with 35mm prints? Is that going to be a thing in 2027? It is going to be like, “now we sell little film prints that you can play at home”, because that’s the kind of madness that happens. And you know what… brilliant. If that comes back, I’m totally down with that. I would be the first one in line because it’s my childhood as well. That’s what we do. We’re big kids.

I know it might be a bit premature with The Green Sea only just being released but have you got any other film projects in the pipeline?

Actually, yes. I’m definitely going back to horror now. I did my drama thing. That was good. I enjoyed that. Now back to horror… way back to horror. I’m working on something. I haven’t got a title yet, but I’m hoping to start shooting next year. I won’t get into many details because that’s generally not advisable. But yeah. We’ve got a horror movie that we’re kind of at the beginning stages of now in terms of putting it together. So I hope, covid allowing, we start shooting by sort of autumn time of next year, which would be great. Hopefully this movie does well because I’d love to be able to get paid. I don’t need a lot of money, just the symbolism of being paid rather than having to spend my own money, because even any of the wages that I got in this, it was all reinvested in the movie. I made zero out of this movie. In fact, I spent more of my money that I didn’t even have. But I don’t do it for money, I do it for love. If I didn’t have any money, I would make a film with my phone. I just would like to have something so I can get good actors or have a decent sound system. Otherwise it’ll just be my selfie stick and my dogs, probably.

Thank you very much for you time, Randal.

The Green Sea is out now on digital platforms such as Amazon and iTunes.

Be the first to comment