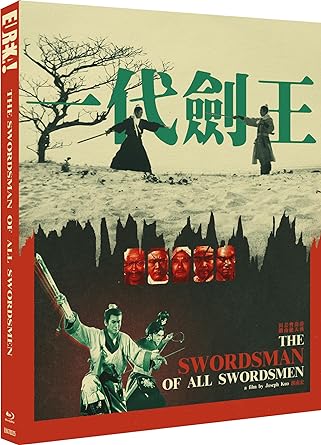

The Mystery of Chess Boxing, The Swordsman of All Swordsmen (1968, 1979)

Directed by: Joseph Kuo

Written by: Chiang Shui-Han, Hsu Tien-Yung, Joseph Kuo

Starring: Jacl Long, Lee Yi Min, Mark Long, Nan Chiang, Peng Tien, Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan

HONG KONG

THE SWORDSMAN OF ALL SWORDSMEN [1968] AND THE MYSTERY OF CHESS BOXING [1979]

AVAILBLE ON LIMITED EDITION BLU-RAY: NOW, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

DISC ONE

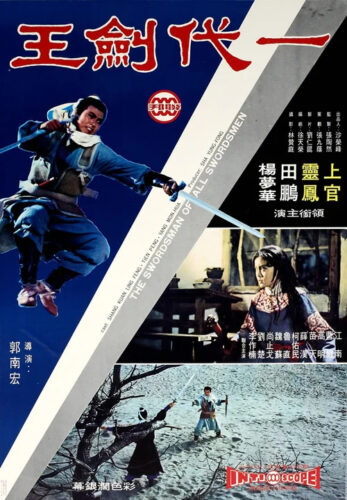

THE SWORDMAN OF ALL SWORDSMEN [1968]

AKA YI DAI JIAN WANG

RUNNING TIME: 85 mins

Tsai Ying-Chieh has trained for many years since his entire family were killed twenty years ago, including his mother and father right before his very eyes. He kills two of the five culprits, not to mention anybody else who gets in his way. He’s getting the job done, but then he runs into another incredible fighter, Black Dragon, a swordsman dedicated to being the the best of the best, even if that means that he must wait and help Tsui pay his blood debt to his family before they inevitably fight to the death. And the pair are then joined by Golden Swallow, a young lady who’s on a collision course with Tsai due to whom his final target is….

I’m going to admit right away that I hadn’t even heard of The Swordsman Of All Swordsmen, but I’m also going to state right now that it’s a neglected classic of martial arts cinema. It’s clearly heavily influenced by Dragon Inn and The One-Armed Swordsman, two films that were huge hits at the Hong Kong box office, so that lots of producers decided to cash in on their success, fighting with weapons especially swords becoming the big thing for a few years until empty-handed combat eventually partially took over. However, this first martial arts film from Joseph Kuo, one of the premiere Taiwanese genre filmmakers – check out my review of a nice sampler of his work in the genre which was an earlier release from Eureka – is a very fine product in its own right, a film which I was truly impressed with and genuinely enjoyed more than its inspirations. Its premise is pretty basic, and for a while it does seem like it’s just going to be one fight scene after another, but as it progresses it becomes more and more interesting, a surprisingly complex look at the idea of revenge with characters we care about and understand. For example, have you ever seen a martial arts movie where, when the hero finally faces off against the person who’s wronged him, and we don’t entirely want said hero to win because his opponent is not vulnerable due to a dis? And, while the frequent swordplay might seem a bit slow and clumsy by the standards we’ve become used to, the more realistic approach also has its bonuses, while there’s great use of the mostly outdoor settings, culminating in one of the best climaxes I’ve seen in ages, beautifully shot and staged on a beach, though the whole thing makes such use of framing that one reckons that Kuo could have become quite something as a filmmaker – which isn’t at all to say that he wasn’t good – but this film suggests even greater and unfulfilled promise.

Opening text informs informs us about this restoration removing lots of dirt and blemishes, along with, apparently, two day for night scenes being corrected “according to the director’s instructions”. Behind the credits rides a man on a horse, traversing road and field, before arriving in a town where he asks three men the whereabouts of a certain Chou Hu. When his question is objected to, he twists an arm and shows his expertise with the sword by slicing off the tops of their hats. Meanwhile a street performer is being harassed by no less than Chou himself, who fancies for himself the man’s daughter. Chou knocks the poor guy down twice and insists that the daughter become his bride; she flees, to run into our hero Tsai, who’s finally found the person he was looking for. “Chou, you haven’t changed a bit, as stupid as ever”, says Tsai, “remember what you said once, all roots must be destroyed”. “Who are you”? asks his target. Now follows the first fight, but despite Tsai being victorious the street performer is dying from his injuries. “Take care of my daughter” he says to Tsai, and one reckons that in an alternate reality Tsai would do such a thing. However, in this reality his mind is only on one thing. He tells her that he didn’t kill this guy to help her, before explaining why and we go into flashback mode, with an excellently handled scene. Yung Chung-chun and his four aides have come for a sword [named the Spirit Chasing Sword in the sometimes more poetic subtitled version] but are willing to kill sixty people too. Tsai’s father fights off a few while having his son on his back, but eventually has to put him down and tells him to “go over there”. He’s old, in fact perhaps unusually old considering the age of his son. His enemies all kill him together but Yung insists that they spare the kid’s life despite Chou’s warning that “all routes should be destroyed”. When everyone’s gone, little Tsai comes out from hiding and picks up his dad’s sword. The emotion is downplayed, yet we still certainly feel it.

The adult Tsai tells the woman that his uncle took care of him and taught him how to fight, that he doesn’t care if he lives or dies, and that he can’t care for her because his mission is too important. Yet one really senses a chemistry between the two, and one feels sad. Another time, another place. Tsai goes after his next target, and again seems to easily find him in the street, taking up a challenge to engage in a spear fight. Fang Bao is then himself challenged by Tsai, who tosses him his hand which Tsai’s father had lopped off. “Here, have it back”. Tsai again fulfills his aim but is outnumbered by Fang’s men until he’s unexpectedly saved by Black Dragon, who most definitely wants him alive because he wants to fight and kill him himself, though agrees not to do it until Tsai has killed the last of his targets. Yung is still around, but is now old and blind. The two others who haven’t been dispatched yet go to tell him that Tsai is about and dangerous, but the rather repentant Yung isn’t up for any more bloodshed, so the others go off to kill Tsai anyway. For the second time Tsai has to be rescued – or ay least considerably helped – but this time by a female who goes by the name of Golden Swallow, though the poison in an arrow that hit Tsai is working fast and Golden Swallow has to go visit her teacher and act all humble before a guy who isn’t too happy with the way that she and Black Dragon have been fighting often, in a tiny subplot which could have been expanded. She’s given the antidote when she tells him,” my father helped murder his father, in this way I can perhaps make it up to him”. Learning this information before even halfway adds to the intrigue. “Don’t you know that hatred can become an obsession, there’s no end, except for even more hatred” she says to him, trying to talk him out of killing her father. Who will survive in this clash of four very different individuals who we all like in very differing degrees?

The outcome may surprise, though it may be the surprise of disappointment for some seeing as what appears to be the final fight isn’t aiming to be a thrilling set piece at all. Instead, it’s going more for asking the viewer to question our hero’s aim and to ask him or herself who he or she roots for – which isn’t either participant really. But those who are itching for a proper end showdown do get one afterwards with that afore-mentioned showdown on the beach, which, like Japanese Chambara actioners, has our participants spend more time standing and posing than having their blades clashing, while it begins by a single dead tree before moving into the water. The first fight has Tien Peng as Tsai fight a few guys before battling his real target in a courtyard; he takes his sword off him, then throws it at him and pins him against a tree, later on he knocks an opponent’s sword into the air, then knocks it into him – and after that drives a sword through a guy so he’s suspended off the ground. This and some trampolining, as is often the case in these films, jars somewhat with the general attempt at realism with the fighting, which won’t seem that crisp now but certainly was at the time. The second fight moves onto a field beside a lake where we get a great moment where the camera tracks Tsai, not that clearly seen because of the long grass between Peng and the camera, as he slashes his way through several opponents. This is bordering on the once critically mocked – or more than that just ignored – Asian martial arts movie being art. Then there’s the obligatory confrontation at an inn where Tao hurls chopsticks into a hand, in a film with a fair bit of the red stuff. It’s when this conflict moves onto another beach at either dusk or dawn [it’s hard to tell but the “corrected” day for night ain’t bad really] that Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kua is allowed to show some moves as Golden Swallow, and she does again soon after, though otherwise she does disappointingly little seeing as she was a bit of a martial arts star of the time.

Just after half way through, action takes a back seat for a while as the drama moves to the forefront, but we get so involved we don’t mind, and the thing still moves extremely quickly. Perhaps the best scene dramatically is when Tsai visits and confronts Yung after so many years. Yung is not just respectful but rather humble, expressing his regret over his past crime, asking Tsai for forgiveness, and even offering to cut off his hands as penance so that the fight doesn’t need to happen. This is visually expressed in a nice shot where Yung seems hemmed in by his surroundings on the exact left hand side of the frame while Tsai is on the other side. And then Yung sheds a tear. We’re so touched by the Yung character despite certain discrepancies regarding his blindness which stick out in a generally well thought through film. Of course it’s Golden Swallow who really sets an example. She may soon realise who Tsai is, but, while we clearly see her strong emotions in what is really effective acting from Ling-Feng without being always asked to say much, but as far as we can see isn’t that interested in using violence to stop Tsai, words being her preferred option, in a ffilm that’s curiously but definitely anti-violent; quite an achievement considering the genre which it’s in. As for Black Dragon, played a little mysteriously by Nan Chiang, we like him less than either of the other two [or should that be three?] lead characters but we do understand his need to prove himself, and eventually we do really like him too. And Feng’s performance is nicely judged; just check out the not overdone expressions he makes after he’s killed one of his targets, showing that he’s not entirely sure about what he’s doing.

The cinematography from Lin Tsu-Ting provides a high number of precise compositions, and a lot of graceful with slow pans and zooms, though some shots are partly out of focus, probably due to the anamorphic format which also causes some edge flaws. The music, all stolen probably from American or British productions though I didn’t recognise any of it, works very well in enhancing the drama in the later sections, though the poor recording of the English dubbed version makes some of it sound a bit tinny. The Swordsman Of All Swordsmen really is quite something though. It’s about more than just fighting, and ends up being a cry for peace.

Rating:

“THE SWORDSMAN OF ALL SWORDSMEN” SPECIAL FEATURES

1080p HD presentation on Blu-ray from a 2K digital restoration completed by the Taiwan Film Institute

The picture quality isn’t too good for the first two minutes, but then it seems like we’re watching a different film when the credits end, and the impressive quality continues; blurry shots, as I mentioned earlier, were as a result of the filming and therefore couldn’t be corrected.

Original Mandarin audio

“Classic” English dubbed audio

Text warns us that this dub was in a poor state, and indeed it has some audio problems, not just sounding rather murky but the soundtrack wobbling and jumping on some occasions, playing havoc with some of the music. While I still mostly watched this version, I did switch on the English subritles for the Mandarin dub, and there’s a lot of difference between what the subtitles read as and what people say in English, the latter sometimes drastically simplifying matters and losing some nuance. The low point for the English dub could be when somebody says “the mountain eventually decided to come to Mohammed”. A tiny snippet of dialogue resorts to Mandarin with English subtitles, presumably because it was, for no apparent reason, cut from the western release.

Optional English Subtitles

Brand new feature length audio commentary by Asian film expert Frank Djeng and film writer John Charles (The Hong Kong Filmography, 1977–1997)

I’ve heard so many of these things I honestly can’t remember if I listened to a previ0us one with talk track stalwart Djeng, who’s often paired with various others, and Charles, but this one’s certainly good; even if Charles is obviously far away, the two still interact well, Djeng having a bit more to say though certainly leaving room for Charles to chime in on various subjects. We learn that Kuo may have impressed with this screenplay but, after being asked to also direct, was really unsure of himself and even delayed production for three weeks while he drew two thousand storyboards, that there were two semi-sequels while Kuo’s script for a proper sequel went unfilmed, and that these films were poorly released in the west, with this one eventually coming out in the US, but just to drive-ins, after the Brue Lee films were huge. Best of all for me is that Charles identifies the pieces of music used in the film. As a film score lover, I’m thinking that it would be great if all commentaries could do this!

Return of the Master: archival interview with director Joseph Kuo [14 mins]

I couldn’t find out what earlier edition of the film this was from. Kuo, happy at being about to go to a retrospective of his work in Paris and his work being taken seriously, says how he began writing unpublished novels before turning them into screenplays, and that The Swordsman Of All Swordsmen was actually shot jus after Dragon Inn‘s completion but not its release, which contradicts what others have said. I’m tempted to believe Kuo here – but was he really “the first director to make Shaolin movies”? I think not.#

DISC TWO

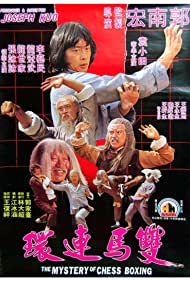

THE MYSTERY OF CHESS BOXING [1979] – Limited Edition bonus disc

AKA SHUANG MA LIAN HUAN, NINJA CHECKMATE

RUNNING TIME: 90 mins

A deadly menace is traversing the land, Ghost Face Killer, who’s challenging and killing seemingly any martial arts master he comes across. Before attacking, he always throws down his “ghost face killing plate,” a decorated metal plate with a red face. Why is he doing this? Ah Pao is the son of one of his victims, and he wants to learn Kung Fu so that he can avenge his father’s death. The Chang Sing School doesn’t want to accept him, and once in he’s bullied and ordered to do menial jobs by the arrogant head student. However, the cook teaches him some moves, though he tells him he’ll never be good enough. When Ah Pao is found in possession of Ghost Face Killer’s symbol, he’s expelled from school, but turns to an old chess master who has a history with Ghost Face Killer….

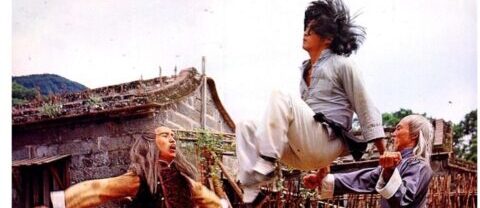

I’m now going to admit something else – it was this second film in this set that I was most interested in seeing. In fact I used to own this on video, though it was quite late in the video era and I believe I only watched it once. Only last night I was thinking how many fans of these movies became fans because a certain hip-hop group, the Wu-Tang Clan, not just sampled dialogue from them but had them be a major element in their whole act, to the point that they ended up starring in a feature-length video where they talked about their favourite martial arts movies and the viewer was treated to loads of juicy clips. The Mystery Of Chess Boxing may very well have been the first one that people hunted down, what with one track being named after the film’s title and one of the group’s members naming himself after the main villain. And that would not at all have been a bad thing, seeing as it serves as a pretty good introduction to the genre, with its archetypal plot allowing most of the loved elements to flourish, including a whopping four young men playing old characters but not looking at all old despite wigs and gray colouring, even though it doesn’t feature any major stars. The fights are often astonishing in their athleticism and come thick and fast without things coming across as “one long unarmed hassle”, as Bruce Lee would have said, though the general seriousness of what we see is undercut by a fair bit of goofy comedy in the first third; it seems so out of place that one wonders if it was included because of the huge success of Drunken Master which was being imitated left right and centre at the time. And, to be quite honest, it’s not made with quite as much care and filmed with as much style as The Swordsman Of All Swordsmen, though that’s probably not the fault of Kuo, who still turns in a well put together product. However, he was now making martial arts films continuously, churning out products on an assembly line, so you weren’t likely to get something with the freshness and style of the 1968 movie. Nonetheless, what a fine assembly product it still is!

Before the credits proper begin, text shows up telling us that the original negatives for this film are lost, and that this Blu-ray was taken from what’s probably the sole surviving 35 mm print, which even contains burned in Cantonese and English subtitles. Then come the seriously cool credits, where, behind the writing and interrupting the writing every now and again at great length, we have miniature martial artists leaping about on a chess board before we close in and get to see two of our main stars showing their stuff and even engaging in a bit of combat. I love it when these films begin like this; it gives us a nice taster and often whets our appetite for the final conflict, though here the second guy is someone who is a good guy in the film. “Chao Yun Lung, how are you”? are the first words we hear as our villain arrives at the house of his next target. “I warn you, you have no chance. You recognise this technique? Five Elements. You remember” he continues as Chao sends away his wife and kid. Ghost Face throws one of his plates at his enemy before the combat begins. Of course he’s victorious, killing him by jumping on his shoulders and crushing his face with his legs – and then, to be sure that we get how dangerous this guy is, we cut to him finding someone else, battling and slaying him, before we meet out hero. He’s on his way to the Chang Sing school to learn Kung Fu, though he’s momentarily distracted by the unnamed [like many characters] granddaughter of an old guy who has some chessboards in a market street. Some students are also there, headed by their senior [Hsiao Hou-Tao in a very Dean Shek-like role] who immediately takes a disliking to Ah Pao, as well as having one of those big moles on his face which were deemed to be very funny at the time by Hong Kong filmmakers, though at least this one doesn’t have hair in it.

For some time, the film, while it never lets us forget that Ghost Faced is about, is comedic, about this unpleasant chap treating Ah Pao like crap and us hoping that Ah Pao will eventually turn the table on him. In the market, grandpa may stop the senior student from actually killing Ah So, but when Ah So finds the school, breaks in and is caught, he has to dodge a sword-wielding guy, then one with a pole, in borderline slapstick bits of fun which are very Jackie Chan-like indeed; the choreography might not be as crisp as we’d have got from Chan but is still pretty impressive. The head student then makes him serve the other students at dinner, making it extremely difficult for Ah Chao because his bowl keeps needing to be refilled, which doesn’t give Ah Chao any time to eat his own portion. He even has to wash people’s feet. However, in the kitchen he meets the chef, who’s played by Drunken Master‘s Simon Yuen. He takes poor Ah Chao’s dinner, then challenges him to steal one grain of rice from his bowl in an extremely clever scene requiring meticulous timing. Ah Pao succeeds only in cheating and waiting for the other guy to finish his meal. He thinks the chef is a Kung Fu master, and is called Master Yuen, so he asks him to teach him. He admits that he will never be good enough, but tells him, “When the time comes to go, I’ll tell you where to go all right”. We also get “Why have you come here to study Kung Fu?”, “to get revenge”, an exchange that must exist in a thousand of these films. It’s here where we get the explanatory flashback, though it surprisingly lacks intensity. Ah Chao gets good at his job, balancing plates that are thrown at him from all directions [clearly for real] and humiliating the head student [serving him urine ho ho ho], but then he’s attacked by the school’s master for possessing this plate, he thinking that Ah Pao’s an accomplice of Ghost Face, then chucked out, just before Ghost Face appears in the vicinity. Ah Pao gets himself taught by the same old guy with the pretty granddaughter, but all he seems to teach him is chess!

What good will that be against Ghost Face, who’s killing all these guys for a reason that will be revealed, but who has an ultimate target by the name of Chi Sue Tin. Well of course chess turns out to be very useful indeed. As master says, “the first virtue is to be calm, calm must be the basis of Kung Fu”, and eventually Ah Sao is spreadeagled and tied to a wall while bricks are placed on small ledges below him so his arms and legs are increasingly stretched, the one sole bit of comedy in the second half being when the granddaughter is annoyed at Ah Pao’s lack of interest in him, despite he having got distracted by her several times before including a pretty goofy love at first sight moment, so she puts a whole load of more bricks on. This leaves the romantic element hanging. it never being referred to again and the lady only appearing once more and very briefly. The training is pretty good and the fights are really good, employing all sorts of martial arts, particularly when Mark Long as Ghost Face is doing rings round various opponents, though we don’t see one particular death move that he does, the film instead cutting to a door. Lin Yi Min as Ah Pao isn’t required to fight properly much until the climax, with even his final encounter with that pesky head student cut short so that Ghost Face can take over. Even near the end fight Ah Pao is clearly not ready in time, meaning that he gets help. Two or even three good guys against one bad guy wasn’t an uncommon sight in Hong Kong movies. To many of us westerners it might not seem fair, but it makes sense if the bad guy is extremely dangerous. The “Double Horse Style” final moves are brilliantly pulled off, but then again just look at all the backflips that Yi Min does. The fights also often have combatants being on the ground almost as much as standing up, a great deal of effort being employed throughout to make these sequences as purely exciting as possible, with the result that us viewers feel a bit exhausted, but in a good way of course.

Even when channeling Chan rather too much, Yi Min is a likeable light performer, though of course it’s Long whom you’ll remember much more because he plays such a cool villain. He likes to verbally taunt his victims while performing moves by himself, interspersing the moves with a few words here and there so it takes a while to complete his taunt; it’s a bit amusing, at least in the English dub, but also just great to watch and hear. Long’s screen presence ensures that Ghost Face remains cool even when he accidentally kills the wrong person, mistaking him for somebody else. Another, perhaps even more notable kill, isn’t even shown, and then only briefly referred to, despite the dead person having been an important one, in what is either a deliberate attempt at being sly by Kuo, or evidence that some footage intended to be filmed wasn’t done so, probably due to the production running out of time. Yuen’s character, who’s just like the other Yuen characters of the time, seems to be cut down, with his training of Ah Pao looking rather truncated; perhaps this was because Yuen had to go and basically play Beggar So yet again elsewhere before his part was completed, or maybe the production just ran out of money? There are a few awkward, sudden cuts that may sometimes be due to missing frames, though look to me more like a device which doesn’t really come off. The cinematographer Hui-Kung Chang doesn’t seem to have worked on any other martial arts film. He likes unusual angles during key moments, films the fight sequences in even longer takes than is normal for the period, and almost entirely avoids handheld camera work. Unfortunately every now and again the picture noticeably changes in colour and quality. Mike Leeder has an interesting possible explanation for this on the second of the film’s two audio commentaries.

Unusually the score, credited to Mou-Shan Huang though he probably just found and used tracks that were written by others, doesn’t employ any western film music with the possible exception of some archetypal comedy stuff. While it contains nothing particularly memorable, the Chinese feel of the music goes well with the images. One track comes from Wu Ta-chiang and Lo Ming-tao’s score for A Touch Of Zen. The Mystery Of Chess Boxing may not be in the same class, but then in a way maybe it is. It’s a terrific slice of genre fun, deserving of its cult status, and also extremely representative.

Rating:

“THE MYSTERY OF CHESS BOXING” SPECIAL FEATURES

1080p HD presentation on Blu-ray, scanned from the only known surviving print of the film supplied by collector Dan Halsted (Head Programmer at the Hollywood Theatre, Oregon)

Eureka have done some work on this, and for the most part the print looks clean and sharp, certainly not as poor as the disc’s text might imply, though some hues have inevitably faded. Certain shots DO contain a lot of damage, though the drastic changes in colour might be because of another reason. At the end of the day, this is probably the best we’re going to get, so we ought not to complain really.

Original Mandarin audio

Original Cantonese audio

Classic” English dubbed audio

Of course I watched the film with the English dub which is as flavourful as you could wish for. The burned in subtitles make for an interesting comparison with the dub, often being very different For example, “the spirit of blue dragon unites the body its spirit is vigorous and full” becomes, in English, “I guess you’d thought you’d escape, but I shall get all of you”. Some difference. They will also bring back memories for any fan who got into these films back in the day when they were only available as bootlegs and usually sported subtitles which sometimes made little sense, with certain lines like “and you think he’s a blamed knave” being ones which will raise a lot of smiles.

Brand new feature length audio commentary by Asian film expert Frank Djeng and martial artist / filmmaker Michael Worth

Djeng returns, but now with his frequent commentary companion Worth, and begins by delivering a real odd fact; this film, despite its fame, never received a theatrical release in Hong Kong. He also tells us that Kuo was more of a producer with his disciple Yan Wang doing much of the work, and that even on the Mandarin track everyone’s dubbed. As usual, Worth goes heavily into the shooting style, but also informs us that it played in one Times Square cinema for ten years, as well as mentioning a little favourite of mine which few seem to know – The Seven Commandments Of Kung Fu, which also stars Yi Min. Bravo, Michael! The duo’s love for this film and indeed the genre it belongs to can almost be smelt.

Brand new feature length audio commentary by action cinema experts Mike Leeder and Arne Venema

Beginning with a semi-accurate but perfectly styled bit of dialogue, this sees Leeder and Venema in full flow, even if they’re surprisingly critical of this film – though their complaints do hold water. Leeder tells us that chess boxing does exists, but it consists of chess then boxing [it was originally the other way round but understandably that was changed], that Rza sent somebody out to buy loads of rare Kung Fu movies when he was in Hong Kong and couldn’t get any of them because they just aren’t as popular over there, and has a theory [yes, I’m going to finally tell it] about the inconsistent picture quality that involves the filmmakers using the unused portions of previously used film to save money. Meanwhile Venema says that Yuen, who became a star late in life, basically worked himself to death, that his own grandfather was a Chinese chess champion, and recalls an amazing experience watching Warrior King with a very expressive audience.

Limited edition reversible artwork by Darren Wheeling

SPECIAL FEATURES

A Limited Edition Two Disc Set [2000 copies]

Limited Edition Bonus Disc – “The Mystery of Chess Boxing”

Limited edition O-Card slipcase featuring new artwork by Grégory Sacré (Gokaiju)

A Limited Edition collector’s booklet featuring new writing on both films by James Oliver

Limited Edition Set of facsimile lobby cards and Double-sided poster featuring original release poster

This release from Eureka is a terrific double bill of martial arts mayhem, both films being classics from different eras. They might be Kuo’s two best pictures. I loved both. As usual, the audio commentaries add considerable value. Highly Recommended!

Be the first to comment