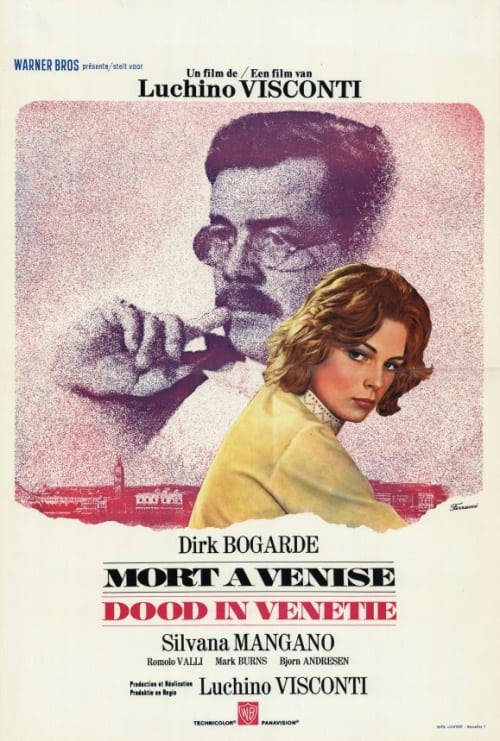

Death In Venice (1971)

Directed by: Luchino Visconti

Written by: Luchino Visconti, Nicola Badalucco, Thomas Mann

Starring: Bjorn Andresen, Dirk Bogarde, Romolo Valli, Silvano Mangano

HCF REWIND NO. 143. DEATH IN VENICE AKA MORTE A VENEZIA [Italy 1971]

AVAILABLE ON DVD

RUNNING TIME:126 min

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Composer Gustave Aschenbach arrives in Venice. He has suffered a period of deep stress and is there to both relax and regain his artistic muse. He soon develops an attraction to an adolescent boy, Tadzio, on vacation with his family. The boy embodies an ideal of beauty that Aschenbach has long sought and he becomes infatuated. However, there is a deadly pestilence in Venice….

Most claim that life is being lived faster than it used to be. People are constantly saying their lives are too busy to do certain things. When I went on holiday to Paris a couple of years ago, one of the most pleasing things for me was that folk seemed to be more taking their time with everything. More people were just taking time to enjoy their surroundings, the atmosphere, and the company. And it’s the same with Death In Venice. It’s very different to most films, which are rightly concerned with telling a narrative as economically as possible. It’s a film of incredible slowness where, on the surface, little happens. It barely even has a plot. Instead, you’re intended to soak up the mood and environment while absorbing every look, every bit of movement, every bit of detail. I don’t think you’re even supposed to think about it much while you watch it, I think you’re meant more to just let it all wash over you, then muse on what you have just seen afterwards, and there is quite a lot to think about, to the point where elements have been interpreted in different ways.

To put it bluntly, this is not a film for idiots, nor is it a film for the impatient, though are certainly times when I would rather watch an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie. I believe it is best to enjoy all different sorts of films; okay, there aren’t many rom-coms I like, but the odd one does come along which I find quite pleasing. I first saw Death In Venice as around 14, not really the best age to appreciate a film like this, and was both bored and captivated at the same time, if that makes any sense. It stuck in my mind for years, and when I saw it again at around 20 I knew I was watching a masterpiece. It’s almost as artistic as a film can get, a movie which belongs more with the great works of painters like Picasso or Michelangelo than with most other films, a film which deserves to be hung up in a gallery and looked at and studied and interpreted. Is it actually enjoyable? Well, it’s certainly not something to put on if you’re feeling a bit ‘down’, but it is enjoyable if you know what you’re about to see. Every time I watch it, and that’s not too often, I absolutely love the mood and heart-rending melancholy of the film, and feel I am viewing something of great profoundness, but feel emotionally shattered afterwards. It’s a masterpiece, but needs a certain kind of mindset to get through. Of course, you also have to except that its hero might have paedophile leanings, and understandably that’s enough to put many poeple off, but consider that there have also been plays and would you believe it ballet based on the material.

It was directed by Luchino Visconti, one of Italy’s greatest filmmakers in a country absolutely rife with great filmmakers. He began the Italian neorealist movement but later his work became more personal, very influenced by opera and exploring favourite subjects like the decline of the ‘old order’ and decay. Death In Venice was the title of a 1912 novella by Thomas Mann inspired by the writer’s fascination with a young boy, though the main character was a combination of homosexual poet August von Platen-Hallermünde and composer Gustav Mahler. Visconti and Nicola Badalucco adapted the novella quite closely. Because of the extremely languorous pace of the film Visconti intended to make, not much was actually added to the novella and many scenes transcribed exactly. Star Dirk Bogarde, an English matine idol turned ‘serious’ actor, had just been in The Damned for Visconti and later said his performance in Death In Venice was the peak of his career. 18 year old Bjorn Andresen, as the object of his affections, became a gay sex symbol after the film and hated it. Warners, fearful of the subject matter, didn’t want to release the film in the US until it was well received in the UK. Then again, the Warner executives were not all the brightest of chaps. After the first screening, one of them asked who did the music. Visconti largely used the music of Mahler, and replied to that effect. “I think we should sign him up” said the exec.

The film opens with the highly symbolic image of a steamer blowing black smoke nearing Venice, and you’ll know if you’re going to enjoy it or not in the next few minutes, where for what seems like ages we fixate on Aschenbach on the steamer, looking out at the dawn, and by the way you’ve rarely seen a dawn like this, gorgeous but eerie and ominous, the first of many incredible images in the film from cinematographer Pasqualino De Santis. Aschenback arrives at his hotel, and the time is taken up with him settling in. The pace is positively arthritic, but this is because Visconti wants to feel every locale, to really imagine you are there, or imagine you are Achenbach being there. He sits in the main lounge of the hotel, which is full of guests waiting to be seated. The camera slowly explores the huge room, possibly becoming Aschenbach’s gaze, possibly not, picking up bits and pieces of conversations [non-English dialogue is not subtitled, a touch that works especially well- you pick up stuff if you know some of the language]. You can almost touch the furniture, you can almost smell the flowers. And all the time, De Santis creates amazingly elaborate compositions incorporating virtually every colour you can think of.

So Aschenbach falls in love with young Tadzio, one of four children staying at the hotel, and plotwise all that really happens is that he follows him around until he dies [and I doubt this is a spoiler, going by the title]. The only conventional bit of drama is when Aschenbach tries to do the right thing and leave Venice, but due to events outside his control, ends up staying, and Bogarde manages probably his only smile in the film, pleased that things have transpired to ensure that he remains in Venice after all. This is despite Venice, however beautifully much of it is photographed, being a city of death, even deadlier than the Venice that Donald Sutherland would find himself in two years later. A lethal cholera epidemic is taking over the city, not only killing off its citizens but representative of the corruption and decay of the very rigid and moral Aschenbach. At one point Aschenbach literally stoops through what looks like hell to keep up with Tadzio. Tadzio, meanwhile, is like the Angel Of Death, the friendly being who welcomes people into the next world. Aschenbach is dying, and to be honest is not dying in a pleasant way, but Tadzio makes it almost a pleasurable experience, even if the two never actually talk.

Tadzio, more than anything else, represents the absolute perfection of beauty, something that Aschenbach has strived for all his life. Dotted throughout the film are flashbacks which either put this into more context or tell us a bit more about Aschenbach’s life. He has intellectual conversations with a friend about whether the emotional or the technical approach is best for art. He is seen to have had a wife and daughter in a truly gorgeous tableau depicting a kind of paradise on earth, three people playing in a sloping garden in front of a country house while the Alps are in the background. We discover that the daughter died, which hints to us that maybe Tadzio could also remind Aschenbach of her. Maybe he wants to adopt him as a son. Then there’s also an inconclusive visit to a brothel [was this inspired by Proust?] which possibly makes the homosexual aspect a little more obvious. The novel was more ambiguous about this, and many felt that the gay Visconti vulgarised it by being a little more explicit in this respect. Tadzio may not only represent lost youth to Aschenbach, but possibly also a homosexual life he wishes he had. Whether he actually physically lusts after him is open to debate. In one important moment, which some who attack the film for its most unsavoury aspect seem to ignore, when he imagines himself warning Tadzio and his family to leave Venice, he is actually seen to stop himself having a paedophilic thought about him.

Throughout, the Adagietto of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony plays, adding its own almost indescribable melancholy to the proceedings. I don’t think any other piece would have worked so well, though some might say it enhances a slightly sick romanticism. In any case, the piece is now associated with the film. The Sehr Langsam Misterioso From Symphony No.3 is well used in one section to both represent an example of Aschenbach’s music and the complex emotions on display. What humour the film has is relegated to a group of annoying musicians, one of which not only looks like death but sings what seems to a variant on The Laughing Policeman, and the incredibly sad scene where Aschenbach gets someone to make him look young again and ends up looking horribly pasty-faced. Bogarde is totally and utterly amazing as Aschenbach, and yet he hardly does or says anything. Instead, he gives you clues as what is going on in his head by subtle expressions. When he first sees Tadzio, you are treated to what is virtually a master-class in perfect acting, Bogarde conveying his differing emotions; confusion, fascination, love etc. with economy yet depth of a kind you rarely see. He never makes Aschenbach too sympathetic; throughout I tend to pity him than anything else, but Bogarde does make one understand some of his complex emotions. Meanwhile Bjorn Andresen is not really required to act, he’s just required to be a presence, and he certainly achieves that.

Death In Venice finishes with one of the greatest death scenes in cinema. Aschenbach doesn’t get any closer to the beauty that he is captivated by, but dies when that beauty seems to reach perfection in his eyes, even if it’s a fallacious idea of perfection, something indicated by the play fight Tadzio has with a friend just before. Unlike most others, who settle for and are content with something not too immaculate, artists often foolishly strive for perfect beauty, in the process foolishly ignoring that its the imperfections that often make us really feel the beauty. Aschenbach sits on the beach in his chair, mascara running down his face while Tadzio stands in the water in the distance, like a Greek statue of a God. Nowhere else in cinema has yearning for what is unobtainable been better portrayed in a single transcendent moment. I never quite cry, but am touched in a more complex way. I can’t say I totally love this film; it has a certain distance to it, and it sometimes feels that so much effort has been made to make things so perfect that a bit of life has been sacrificed in return, though isn’t that ironically suitable considering some of what it’s about? In any case, Death In Venice is one of the great works of art….and not just of cinema….but of all mediums.

Be the first to comment