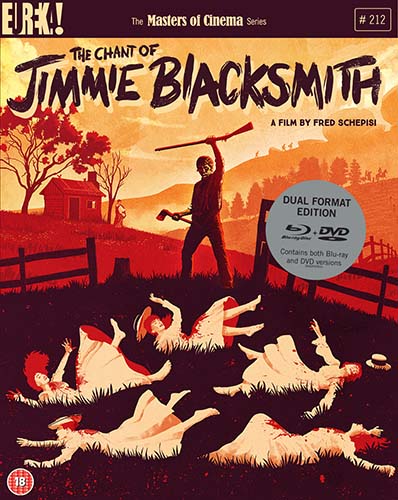

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978)

Directed by: Fred Schepisi

Written by: Fred Schepisi, Thomas Keneally

Starring: Freddy Reynolds, Jack Thompson, Ray Barrett, Tommy Lewis

Australia

AVAILABLE ON DUAL FORMAT BLU-RAY AND DVD: 26TH AUGUST, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

RUNNING TIME: 122 mins/117 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Jimmie Blacksmith, a half-caste child of an Aboriginal mother and a white father, is raised to adulthood by the Reverend Neville and his wife Martha, hoping their influence will “civilise” him and provide him greater opportunities in early twentieth century Australia. He goes out in search of work to establish himself, but is constantly taken advantage of by employers. Even marrying a white girl, Gilda Marshall, fails to change things. Eventually he enlists a his uncle Tbidgi to help him put a scare on the Newby family who are withholding his wages, a scare that goes horribly wrong….

Many of us, especially horror lovers, like to talk about scenes from films and TV that frightened us when we were young. Slightly less of us seem to mention things that shocked us. But I will never forget my first watch of The Chant Of Jimmie Blacksmith when I was about 12 or 13 on TV. Here we had this film where, for over half of its running time, I was totally on the side of its main protagonist, a person continually insulted and mistreated because of his race. And then suddenly he and someone else [though he acts first] committed an act of such shocking brutality that I found my sympathies suddenly altered and I didn’t know how to take it. Was I still supposed to care for this man after this? And then for god’s sake he went and did it again, finishing the moment by adding a baby [yes, a baby] to the women, children and the one man he’s either shot or axed to death. Seeing as every synopsis of this film I’ve read mentions most of this, I don’t really count it as a spoiler, though I obviously hadn’t known about it when I watched the film on that night. Of course most readers of this website will have seen more graphic killing scenes, but I’m not sure that I had at the time, and in any case it was the sudden eruption of violence that was most jolting and horrifying. When I mention this during conversations nobody has ever heard of the film, which is a crying shame because I feel that it’s one that every adult should see if they think they can take it. It’s one of the best movies ever made about racism, a truly raw and truthful indictment of that terrible disease that seems to be embedded in so many of us, even if we’re not always aware of it, and don’t worry – this is not some preachy, sentimental, PC-filled handling of the subject which it probably would be if it were made now. Goodness, even most of the language in it probably wouldn’t get through nowadays.

It was adapted quite closely from the novel of the same title written by Thomas Keneally [Schindler’s List]. He’d based his book on the life of bush-ranger Jimmy Governor, an Indigenous Australian who, along with a friend, massacred a whole household and caused a huge manhunt while an atmosphere of terror gripped part of Australia and brought business to a standstill. Writer/director Fred Schepisi managed to raise the budget in only three months from a variety of sources; $350,000 plus a loan of $50,000 from the Australian Film Commission, $350,000 from the Victorian Film Corporation, $200,000 from Hoyts, along with $250,000 from himself. Star Tommy Lewis was spotted by Schepisi’s wife at Melbourne airport just walking past. He and also first-time actor Freddy Reynolds had to rehearse with things deliberately going on behind them so they knew what it would be like acting on the set and the locations. The distance traveled to and fro the various locations was the main reason that this ended up being the most expensive Australian film to that date. The original cut ran 122 minutes, though it was distributed in most places overseas in a slightly shortened version running 117 minutes except in the UK which had the 122 minute cut shown in cinemas even though it was the shorter edit that then came out on video. It was nominated in every feature category in the 1978 Australian Film Institute [AFI)] Awards except for two, but only came away winning three, while it wasn’t a box office success either, drawing much criticism over its subject matter and violence in its native country, and not being shown on TV there for 20 years. While not prosecuted for obscenity, the film was seized and confiscated in the UK during the video nasty panic.

I’ll first mention again the language here, because there’s so much sensitivity about this kind of thing these days, to the point that it’s sometimes becoming unrealistic where you get racially themed films where characters don’t always speak like they actually would do, especially with movies set in the past – something which I consider to be downright dishonest. In this film, right from the very beginning you hear ugly racial slurs and they rarely stop. I personally don’t see it as a problem, this is how many white Australians would have spoke of and to the Indigenous Australians, but be warned. Anyway, the very first scene sets out this world very adroitly, the opening shot being of a small Aboriginal community living in virtual squalor before we pan back away from the window we’ve been looking out through and into a fairly lavish interior and a white man saying to his wife; “blasted blacks”. The man is the Reverend Neville, and he probably believes he’s a man of God. One of his “missions” is to imbue a “black” with “decent ambition”. He says the most repulsive thing that he no doubt genuinely believes is not “wrong” at all. He takes the young Jimmie in after beating him for not attending school and hanging out with his tribe instead, and after a few years tells him to marry a white girl because then; “your children will be only quarter caste, and your grandchildren only one eight caste, scarcely black at all”. He genuinely wants the Aboriginals to be eradicated. If you really think about it, what he’s proposing isn’t really any different to Jimmie’s murderous “war on whites” later. This was the first time that I’d watched this film since that first time, but being a great deal older made me far more aware of the horror of much of what’s said and shown, another example being the state of the indigenous population which is heartbreaking to see. All we see are poor drunks often looking terrible. Just as alcohol played a major part in the subjection of the Native Americans, it was also employed to take Australia away from its original owners. Well – that, and, as schoolteacher McCready says much later; “religion, influenza, measles, syphilis, school”.

Poor Jimmie, being a half breed [perhaps the one significant alteration of the true events], is caught between two ways of life, and can’t fully cross into either of them. He’s periodically drawn to his people with whom he spent his first few years, though he can see that they’re losing their identity and have virtually nothing. All they seem to want to do is sit around and get plastered. He appears to have a girlfriend, leading to an uncomfortable scene [well, this film’s full of them] where he’s having sex with her and is virtually taunting her during the act; “what is your animal spirit?”. The Reverend’s teaching has made Jimmie determined to make something of himself, and he proves himself skillful at building fences, but every employer fiddles him. He also works as a policeman, but is used by Inspector Farrell [a very rounded and thoroughly convincing portrayal of nastiness by Ray Barrett] to capture a former friend who is later beaten and murdered while in custody, and forced to cover up the death in a terribly sad scene that probably hits harder than Farrell viciously attacking some Aboriginals so one of them tells him some information. One of many instances of foreshadowing [notice all the shots of axes] includes Farrell suggesting to another that he get his fiancee in “the family way” to ensure that she stays with him. Does this help make Jimmie want to have a fling with and then marry Gilda? I’d have liked to have seen a scene or two between their opening sexual encounter which seems spurred on by both parties just wanting to sleep with somebody of another race, and him about to marry her, but never mind. Terrible embarrassment takes place, but Jimmie sticks by her. But they’re running out of food because his current employer won’t pay him. Despite knowing full well what was coming up, I was still shocked this time around, but also noticed how Schepisi tended to actually cut way from or only briefly show gory detail while the camera moved around and didn’t dwell on anything, yet was still able to achieve a powerful effect and even touches of visual poetry, like blood spilling onto the floor having water spilled onto it.

And this time, because these days I like to be challenged, I loved it that my emotions were being toyed with so much. Did I want him to be hunted down, or did I want him to get away? How much blame for his killing was I supposed to lie at the society that he lives in? Is an individual fully responsible for his actions? Such questions aren’t answered, leaving the viewer to attempt to make up his or her mind. Conventional emotion is avoided, but by the time of the predictable [but it’s the only way things can end] ending one still feels quite shattered. The manhunt section of the film could have picked up the pace a little, with much dwelling on the natural environment a la Walkabout, but the backgrounds are often cleverly used – after the rampage Jimmie is literally part of a tree that’s falling apart, just like his life, and there’s some nice characterisation, such as the butcher who also works as a hangman and is neither excited nor horrified at the prospect of having to hang more people. He’s found a way to divorce himself emotionally from his horrible job but is still an odd counterpoint to Jimmie. I wish I’d learnt more about Gilda, she’s thinly sketched and a scene or two involving her, including what ought to be a major confrontation between her and her husband, seem to be missing. But generally Schepisi, who like several other directors of the Australian New Wave who caused a stir then moved to Hollywood, succeeds tremendously well with what is really difficult material. The film also refuses to demonise all white people and certainly doesn’t depict the Aboriginals as saints either even if you’re rightly more on their side. He makes us aware of the political situation of the time where the British colonies in Australia joined together to form the Commonwealth, totally leaving out the Indigenous Australians in the process who ended up in an even weaker position, without detracting focus from the main story. His film certainly feels authentic, including the Aboriginal rituals which aren’t necessary in plot terms and which we don’t seem to be invited to understand, yet which add more flavour and a certain mystery.

Lewis is sometimes a bit awkward in his line delivery, but it kind of suits the role and he has very expressive eyes that are able to burn with rage even if he’s trying to hide behind a mask of complacency. Once he shifts into aggression of his own his performance becomes more intense. And Reynolds as his brother Mort is simply wonderful, full of a somewhat cheeky personality yet very powerful when he needs to be. His character becomes something of a voice of reason to his brother. Some may find Bruce Smeaton’s score to be too emphatic, though it’s more the loud volume at which it’s recorded then the music itself, which has a rather lyrical main theme that emphasises the overall tragedy of the piece. And I’m sure if it were made today, many would say that it needed an Aboriginal filmmaker to direct it. it’s interesting to note that Keneally, the writer of the book, says that he’d write the story from a white perspective rather than Jimmie’s if he wrote it today. I’ve personally never agreed with that kind of thing, I feel that if you have some understanding and empathy then what’s the problem? – though delving into that is probably beyond the scope of this review. In any case, while I like to think that we’ve moved on since the year of its release 1981 with regard to racism, and it doesn’t really seem to directly comment on 20th century issues anyway, The Chant Of Jimmie Blacksmith still strikes a most powerful and potent chord even today.

Rating:

This was previously out on Blu-ray in Australia from Umbrella Pictures, and I expect that Eureka are using the same restoration, though they’ve probably done their own tweaking. Generally it looks fine, if perhaps overly grainy [I like grain, but not too much of it!], and blacks can be a bit blotchy. But this film was probably shot cheaply and I’m sure that the restorers did what they could. Detail, especially on people’s faces, is very strong and the mono audio really quite forceful when music and certain sound effects like screams are heard. Interestingly the two versions look a bit different. While it’s not really noticeable if you just watch the Australian version, putting on the International version immediately afterwards indicates that the Australian version has very yellow-emphasised colour timing, though don’t worry, it’s nowhere near as extreme as that notorious restoration of The Good The Bad And The Ugly. I personally prefer the slightly darker look of the International version[which has been restored by Shout! Factory], though it’s seemingly missing five minutes. I skimmed through the International cut and didn’t notice anything missing, so I guess it must be slight scene shortenings.

Eureka have ported over most of the extras from the Umbrella. A Schepisi introduction and footage from the premiere is lost, but a Schepisi interview, an extra audio commentary and the inclusion of the International version more than make up for this. The new commentary features Alexandra Heller-Nicholas who did a similarly scholarly yet easy to understand track on Eureka’s release of The Incident, though this one is more diverse in its analysis. She doesn’t seem to feel comfortable being a white person discussing an Australian film written and directed by a white person but about an Indigenous Australian, but thankfully avoids overt PC stuff and delivers a highly observant and informative track which told me something very sad that I wasn’t really aware of – that despite moves in the right direction the mistreatment of the Aboriginals and in particular incidents of them dying in police custody continues. While not often scene specific, certain moments are analysed and both the set and the visual design examined with some interesting points made. The gaps in the second half grow longer, but you’ll be glad you listened. The older Schepisi track makes a fine counterpoint, sometimes skimming over the areas Heller-Nicholas covered more, but mostly focusing on the production, and making some important points like how approaching such a tale from a modern perspective is dishonest. He goes into his method of filming and how he used such devices as shooting the indigenous people as part of the landscapes and the whites sticking out of them, and tells of how he originally envisaged the film told in flashback. He apologises at the end if he was boring, but he certainly isn’t despite his relaxed manner.

The second new special feature follows. The interview with director Fred Schepisi doesn’t have much about The Chant Of Jimmie Blacksmith but has the filmmaker talk in great detail about his approach to making movies, covering topics such as the differences in approach between adapting the works of others and working from original stories, and finding a way to convey the worlds of different environments and types of characters. He mentions but doesn’t name a script he agreed and was keen to do because it was better than the fifty previous scripts he’d got sent but then left the project when he realised it was still rubbish. I wonder what that film was? All certainly interesting to me, though many will enjoy more the first of the older extras, Celluloid Gypsies: Making The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith has Schepisis, Lewis, cinematographer Ian Baker and editor John Kavanagh go through the often very primitive and tiring production and we learn that, for example, the mass killing was originally shot in one take but lacked power so they then shot it more conventionally and used bits from both edits. The recollections of Reynolds are especially worthwhile. It’s horribly telling that he was initially unsure of how to react to Schepisi’s wife first approaching him because people of his race weren’t supposed to look at white women.

The hour-long conversation with director Fred Schepisi and cinematographer Ian Baker repeats some information, but of course the length of this particular one allows for more detail as the two describe working with each, the shooting of the film and the response to it. Schepisi says how, if he walked by a cinema showing it, he would always know if the massacre scene was playing as people would be running out of the auditorium! And wait till you hear his psychiatrist’s response to having seen it. The Chant of Tom Lewis is the rest of the interview from which the Lewis footage for the making-of was taken from. He’s really honest and thoughtful as he reflects on his upbringing [which yes, involved abuse of various kinds], wonders if he would have become an alcoholic and died early like so many of his friends and family if he hadn’t made the film, says how he deals with racist comments which he’s still subjected to, and even mentions his family life. The 2008 Q&A session with Fred Schepisi and Geoffrey Rush has Rush, then members of the audience, ask questions, which are often intelligent even if you’ll have heard most of the answers before. And finally Making us Blacksmiths is a short documentary that looks it was made at the time of the film about Lewis and Reynolds, with a bit of nice behind the scenes footage interspersed with film footage and interviews. You will notice that there’s much repetition of stories by Schepisi, but then some of these features were made at different times and there’s only so much you can say if asked the same questions!

A film which is very powerful and very important backed up by lots of special features – this release comes Very Highly Recommended.

SPECIAL FEATURES

*LIMITED EDITION O-CARD (2000 units) – featuring newly commissioned artwork by Nathanael Marsh

*The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith – Australian Version [122 mins] – presented in 1080p on Blu-ray [with a progressive encode on the DVD], from a restoration completed by Umbrella Entertainment

*The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith – International Version [117 mins] – from a brand new restoration completed in 2019 from the original film elements [Blu-ray only]

*Uncompressed monaural soundtrack (on Blu-ray)

*Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing

*Brand new and exclusive audio commentary by film critic and writer Alexandra Heller-Nicholas [Australian Version]

*Audio commentary by director Fred Schepisi (Australian version)

*Interview with Fred Schepisi [39 mins]

*Celluloid Gypsies: Making “The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith” [36 mins]

*A conversation with director Fred Schepisi and cinematographer Ian Baker [64 mins]

*The Chant of Tom Lewis – interview with Tom E. Lewis [26 mins]

*Q&A session with Fred Schepisi and Geoffrey Rush, from the 2008 Melbourne International Film Festival [34 mins]

*Making us Blacksmiths – Documentary on the casting of Aboriginal lead actors Tom E. Lewis and Freddy Reynolds [10 mins]

*Stills Gallery

*Theatrical Trailer

*Reversible sleeve

*A collector’s booklet featuring a reprint of Pauline Kael’s original review of the film

Be the first to comment