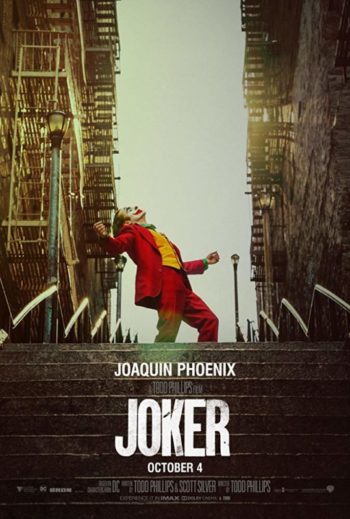

Joker (2019)

Directed by: Todd Phillips

Written by: Scott Silver, Todd Phillips

Starring: Frances Conroy, Joaquin Phoenix, Robert De Niro, Zazie Beetz

JOKER (2019)

Directed by Todd Phillips

With many experiencing superhero/ anti-hero fatigue, Joker goes in a new direction by giving an origin story for the premier villain in DC’s rogue gallery. Since the forties, he’s stood in for chaos, being an unreasoning, unpredictable, force of nature who does violent things for the sheer fun of it. His obsession with corrupting Batman, and having him share in his insanity, has spanned generations and numerous onscreen incarnations played by everyone from Jack Nicholson to Zach Galifianakis. As such, by taking the caped crusader out of the picture, and changing him from a near-abstract emblem into a flesh and blood person, Phillips takes an admirable risk. Which, for the most part, pays off. Sort of.

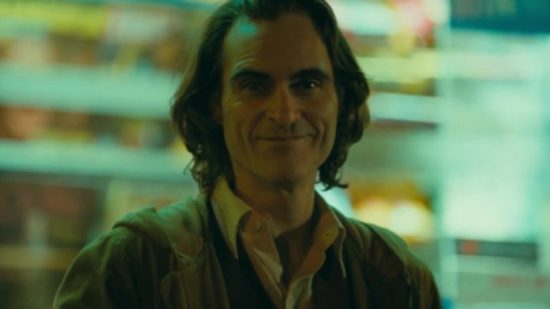

But I’m getting way ahead of myself. Joker tells the story of struggling clown for hire Arthur Fleck (Phoenix): a greasy, ever-thwarted, depressive loner, who lives with his sick mum (Conroy), lacks people skills and has a persecution complex. He also has a rare condition that causes him to burst out into fit’s of spontaneous laughter when he’s feeling anxious. What keeps him going is the dream that one day he’ll make the big time, and get to appear on TV with Murray Franklin (De Niro): a charismatic comedian and talk show host. One night, after a booking goes badly wrong, Arthur accidentally giggles his way into fight with three Wall Street guys and discovers he’s surprisingly good at killing people. He also enjoys it, with the same violence as a form of expression shtick as Alex and his droogs. At first it seems a one-off, but after reports of a suspect in makeup emerge, a sketch of his clown face becomes the unlikely icon for an angry populace. Think of him as a derivative mix of V and Travis Bickle with school shooter angst and a dash of Chewbacca Mom. Oh, and a tonne of Rupert Pupkin (as acknowledged by De Niro playing the Jerry Lewis role).

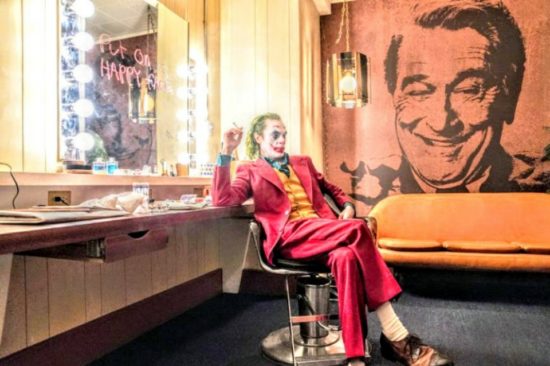

At first, the director of the Hangover trilogy may seem an odd choice for a flick like this: one is tempted to imagine him looking at the footage and asking “why so serious?” However, since his debut was a documentary on the life and times of hard-drinking/ hard defecating punk rocker GG Allin there’s a precedent. Phillips more than rises to the occasion too, with a bold looking aesthetic that combines moments of technicolour beauty with early eighties grime (save for a brief effigy of Trump showing up, it’s ostensibly set then). In doing so he captures the ugliness of an oppressive Gotham gone bad, along with perspective moments that show the kind of fantastical alternative Fleck yearns for. It’s also a lot nastier than I was expecting, really pushing the boundaries of a 15 certificate. There’s a physicality to the violence that gives it a more visceral impact than comic-book fans may expect from the big screen. Still, for the most part, Phillips delicately balances what we do and don’t see to keep us (a little bit) on Fleck’s side. Which brings us to the obligatory questions of if it glories his behaviour.

Though I think it’s been mostly cynical marketing, with publicists amplifying an outrage that doesn’t seem to exist, it’s hard to divorce Joker from the “controversy” surrounding its release. Despite critics, the world over, praising it, the suggestion it may inspire incel violence has come up a lot online – mostly by people arguing against it. Superficially, this concern makes sense, given Fleck shares more than a few characteristics with recent domestic terrorists. His self-pitying outbursts, about how hard it is to fit in with a world gone crazy, also resemble the ravings of Eliot Rogers among other “lone wolves” who couldn’t catch a break. The super slow-mo cigarette smoking scenes also seem designed to give him a sense of outsider coolness. The grotesque caricatures and needless hostility from all corners do too. Yet what I found most surprising about Joker was how little it had to say about anything: something I suspect came from the studio being intent on not offending anybody. For instance, “the clowns” may be equally Trump’s “deplorables” or Antifa depending on how you read into it. Lots of anger aimed in no particular direction except everybody else.

As a state of the nation flick, its empty depiction of a world gone wrong is nihilistic and directionless, making attempts to interrogate the character’s motives or find solutions unrewarding. Sometimes it contextualises the rage as part of a peasant’s revolt, with the wealthy Bat-daddy Thomas Wayne and the rest of the 1% being a political target. Others in this bracket are also depicted as exploitative and cruel. But this familiar premise, already used in The Dark Knight Rises, gets undermined by the horde of thuggish protestors having no clear voice or reason, Fleck’s dislike for Wayne being personal, and his repeated insistence he’s not political. The rich are scum, and the poor are murderous savages – it’s a simplistic world view. There’s potentially an interesting point to make about an angry mob latching on to a symbol and infusing it with significance. However, by giving this symbol such a self-centered voice, it (perhaps unintentionally) reduces society’s problems to an arbitrary game of who shouts the loudest/ whines the most. Thus the movement he inspires has even less of a purpose than the prince of crime had when he was more concept than man. As per everything else to do with Fleck’s turn to the purple side, it just happens: the downtrodden got to kill. Don’t get me wrong, the message of a film doesn’t have to matter provided it’s entertaining – see Nolan’s very conservative take on The Dark Knight. Nevertheless, given its self-important posturing, constant yammering about the society we live in (the line from the meme does not appear), and attempts to frame its titular character as part of a revolution it has to. By forcing its vacuous subtext to the forefront, it left me wanting substantially more or less of it.

Despite his part having very little to say thematically, Phoenix excels in what is by far the most ambitious depiction of the Joker. He inhabits the role well, playing the manic scenes with animated and anarchistic energy that, when juxtaposed with his fragile and erratic downer scenes, give his descent a sense of tragedy. When he says “I just don’t want to feel so bad anymore” we believe him, and maybe even empathise with him. This bond gives his quest to connect with people, through making them laugh and smile, emotional stakes. The balance between making us feel for and fear him is perhaps the film’s most interesting aspect: we can’t decide if we’d hug him or cross the road to avoid him. It makes us invested in a guy who has been failed by cuts to social services but challenges us to say we’d offer him the help he needs. Still, as a film about challenging the stigma surrounding mental health, it falls short. No matter how good his performance is, Pheonix can’t quite sell the villain’s journey that sees him transition from entitled misanthropist to a killer because society has lost its way and he’s off his meds. The first kills make sense, and to an extent the late ones do, but the middle is shaky. Hence his performance sometimes watches more like a showcase of great bits than a fully realised character.

I’d love to say we’ll maybe see something more concrete, in terms of both themes and characterisation, in the sequel. But with Phillips saying this version of Joker will never fight the upcoming R-Patz Batman then I expect this will stay a standalone piece. This news makes the imprecision of its statement all the more disappointing: a striking but shallow origin for a villain who needs a hero to give him meaning.

This score was increased from 3 stars shortly after publication. Joker is out now.

Be the first to comment