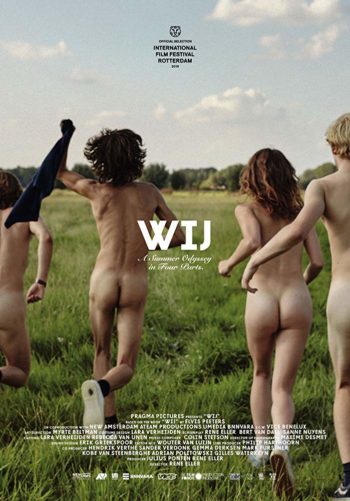

We (2018)

Directed by: Rene Eller

Written by: Rene Eller

Starring: Aimé Claeys, Maxime Jacobs, Pauline Casteleyn, Tijmen Govaerts

WE (2018)

Directed by Rene Eller

The kids aren’t alright. In fact, if you believe the feature debut from Rene Eller, that’s bound to become a cult cumming of age hit, they’re downright awful: genital flashing, car-crash causing, dog-snatching, drug-taking pornographers. It’s a Daily Mail reader’s nightmare. And that’s all in the first half hour. Taking place in a little village on the Belgian side of the border with Holland, We follows the adventures of eight privileged but bored millennials who have hormones “exploding out” of their ears. They are four boys and four girls (can I make it any more obvious?), who discover an abandoned RV in the wilderness. They decide to make it a new base of operations, a commune in which they have the “freedom” to explore their new interests: shooting naughty movies, and other ways to make quick money. The movie’s non-linear timeline charts their corruption from decadence to depravity. It’s a descent we get told from an early stage will end in the untimely death of one group member, Femke: the closest they have to an innocent.

Or so we’re told, learning about her through our four narrators, who are giving evidence into an inquiry into her death. However, without their insistence, I don’t think that many viewers would necessarily come to this idea of her by themselves. It is maybe ironic that, during a movie which explores how individuals lose their identity as part of a collective, the characters meld into one. But for much of the running time, you could substitute who says what and it would not be jarring – including those we hear a personal monologue from. This problem is amplified by the fragmented narrative: a device that keeps the pacing compelling but works against telling coherent individual stories. The exceptions are Thomas – the psychopathic, self-appointed ringleader, and the arty one Lisel (on a side point, given her projects involve lining up aborted fetuses for shock, her aspiration is possibly an example of self-parody, or form unintentionally underlining meaning). I suspect this is at least part of the point since it looks at how group-think can develop, and when logic goes beyond reason as new norms get taken too far. The problem is that we do not get much of an impression of who they are as individuals. And even less of a sense of the normality they are replacing.

When making a movie about young people establishing a counter culture, an important part is exploring the values of the dominant society they set themselves in opposition too. Here our impression mostly consists of short scenes implying their corruption may be intergenerational: the local politicians are sleazy, the workers are sleazy, and anyone of influence elicits the services of child prostitutes. Save for their parents, who are notable in their absence or pushing them to be a part of it. It’s a surface-level commentary that’s functional but not complex enough to contextualise the degeneracy, as much as sensationalise it, and fails to ground the teens’ post-modern sense of disillusionment and apathy in anything concrete. Thus the main message, like the kids used to convey it, becomes quite juvenile, and is difficult to engage with intellectually or emotionally.

I do mean to suggest you won’t feel anything though: We does discomfort better than many other movies of its ilk, which is no mean feat. A common criticism that gets levelled at this sort of film is it’s easy or cheap to do something that makes an audience cringe. However, this kind of argument greatly underestimates how hard it is to shock an audience who have been desensitised by numerous other “shocking” films. And while there is not much on-screen violence, what little there is lands with a (literal) gut punch. There’s a heck of a lot of sex too. Intercourse is the movie’s Poochie – it’s usually in the scene and if it’s not people are talking about it. Among other things, these scenes include graphic penetration, made all the more provocative by how young the characters are supposed to be. Many involve the girls having sex with much older men too.

It is maybe during these scenes that the film finds its most substantial point. That ‘I’ will always come before ‘we’, and the type of liberation the young people in it think they have found can only exist at the expense, and with the exploitation, of others. New members get initiated via sexual exploitation including forced stripping, which Lisel insists is part of being free. Numerous people also fall victim to their reckless behaviour, albeit some more deserving than others. Even within their group, allegedly all in it together, a clear hierarchy emerges under the increasingly immoral Thomas. The bulk of the boys contribute little to their money making schemes, while the girls are further relied on to sell their bodies to fund everyone’s freedom. They also get subjected to far more humiliation and are even on the receiving end of violent acts. Still, there is some light at the end of the tunnel, with one scene suggesting some of them have limits, though these bits are few and far between.

Which is fine – not every story needs to end with the reflections of an older and wiser adult. However, without the necessary work put in to characters or motivation, I think the absence of growth renders much of it quite pointless. Which becomes problematic since it’s neither especially entertaining nor enlightening. However, in its own way, for better or worse I suspect it’ll be hard to forget.

Rating:

Artsploitation Films will release WE on DVD & Blu-ray February 18th and VOD/Streaming April 14th in the United States of America. It will be released on DVD in the UK March 09th.

Be the first to comment