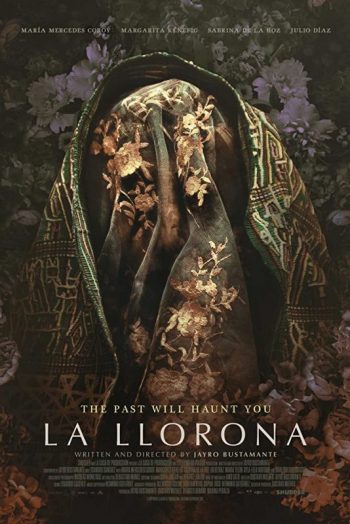

La Llorona (2019)

Directed by: Jayro Bustamante

Written by: Jayro Bustamante, Lisandro Sanchez

Starring: Ayla-Elea Hurtado, Margarita Kenéfic, María Mercedes Coroy, Sabrina De La Hoz

LA LLORONA (2020)

Directed by Jayro Bustamante

Until last year, when the mediocre Conjuring spinoff came out, I’d never heard of La Llorona in my life. Yet, in Latin America, she’s a household name, in much the same way Bloody Mary would be here. Telling the tale of a young woman who drowned her children, and mourns their deaths for eternity, the myth is also a mediation on guilt and reckoning. Both of which make La Llorona the perfect monster for director/ co-writer Jayro Bustamante’s new horror about the worst things humans can do to each other.

General Enrique Monteverde (Diaz) is a former Guatemalan ruler, known around the world as one of the bloodiest dictators of all time. Now in his twilight years, he finally faces justice for the first time when he is found guilty of genocide. Still, due to a technicality, he can go home and stay with his family, including his wife Carmen(Kenefic), and his daughter Natalia (De La Hoz), and granddaughter Sara (Hurtado). This botched legal process is not the end of it, though. Almost immediately, a wave of protesters descends upon his home to chant and drum through the night as they hold up pictures of their “disappeared” loved ones. At first, between the four walls, life goes on as usual save for the odd brick through the window. But, his erratic behaviour means Enrique soon finds himself short of staff, so they have to hire in someone new. Along comes the beautiful (and longhaired) Alma (Coroy), whose name derives from the Spanish for “spirit” – which is fitting, given her ghostly demeanour. She takes an immediate shine to Sarah, who she tells many secrets – including, for some reason, how to breathe underwater.

The contrast between yesterday’s Enrique, a bloodthirsty despot, and the one we see in his now weakened form is staggering. Once a commanding figure who would kill without remorse, there’s almost something tragic about seeing his family take his gun from him in case he harms them by accident. Logically, audiences should hate them all: he committed awful crimes, and they stand by him. His claim that it was only about defence is also a non-starter when 40% of his victims were children under 12. It is a credit to Bustamante as a storyteller that we don’t. What little connection we share with the now decaying dictator may be partly due to the film establishing his vulnerability before we enter the courtroom, as he is awoken the night before by a spirit. Also, since Enrique is the only person who can hear its cries, he acts as our avatar for many of the scary scenes. The film takes on a very intimate style, with the only times in which we leave the family being when Carmen has visions of the crimes committed in their name. Otherwise, we’re situated up close and personal with the Monteverde, in a single location. We see the tensions and conflicts as the candid style makes us feel like we’re among them: a fly on the wall.

As a horror, La Llorona functions well. However, it is also an excellent look at a family falling apart under pressure. Scenes like them struggling to relax in the yard while the drums of the oppressed sound just out of view are striking (although the most effective scene is when they go silent). They love Enrique, though there is only so much they can ignore, or downplay, his evil deeds. Particularly with Sara getting increasingly curious as to why everyone says terrible things about grandpa. He’s an all too believable tyrant, showing no remorse for his crimes after hearing testimonies victims raped by his military, but still having enough charisma to charm his nurse along with possibly large parts of the audience. It is no wonder the others, most notably Carmen and Natalia, struggle so much to align their favourable images of him with his awful past. For reasons I suspect are as much about defending herself as much as her husband, Carmen is quick to dismiss any stories against him – blaming the native women for sexually tempting him and calling her daughter a lefty when she doubts this. When this doesn’t help her, her last defence is that they can’t do anything now anyway. After all, the past is in the past.

Only this time, its ghosts still have a voice in the form of the peaceful barrier of noise outside, which undercuts the domesticity. As the court scene shows, this movie about lifting the veil on awful crimes against humanity and the horrific history of colonialism in Guatemala. There’s also Alma inside the home. She is maybe my least favourite part of the movie, with her emotionless and ethereal mannerisms making her role incredibly transparent. Particularly after she mentions early on that her son and a daughter both died young. Still, I doubt Bustamante intended for things to be ambiguous, and a large part of the tension comes from seeing how her presence impacts upon the rest of the house. She is also our way into getting to know the indigenous staff better – who use witchcraft to protect their oppressors from the consequences of their own actions. Following an anxious second act, focused on the familial drama, the third is an adept series of scares that lead to a powerful finale. I was never particularly scared, and I don’t think any of the set-pieces will be especially memorable, despite their well-judged use of symbolism. Still, the themes and the story come together flawlessly in an angry, and timely horror about something real. Harrowing, moving and urgent viewing. I’m glad I got to meet La Llorona again.

Rating:

La Llorona is available on Shudder.

Be the first to comment