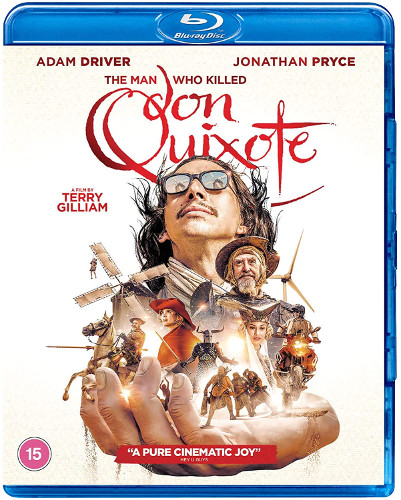

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2018)

Directed by: Terry Gilliam

Written by: Terry Gilliam, Tony Grisoni

Starring: Adam Driver, Jonathan Pryce, Olga Kurylenko, Stellan Skarsgård

UK/BELGIUM/FRANCE/PORTUGAL/SPAIN

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY, DVD AND DOWNLOAD

RUNNING TIME: 132 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

Ten years ago, as an idealistic film student, Toby Grummett wrote and directed The Man Who Killed Don Quixote in the remote Spanish village of Los Suenos. Now the rich, jaded and arrogant filmmaker is back in Spain filming an advertisement featuring Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Realising that the shoot is near where he once made his student film, he pays the town a visit and discovers that Javier, its star, is convinced that he’s the real Don Quixote and that Toby is Sancho Panza his squire. When Javier accidentally starts a fire and Toby gets in trouble with the police for stealing a motorbike, Toby is roped by Javier into a series of adventures in which he’s Sancho to Javier’s Quixote….

Miguel de Cervantes’s 1605 novel Don Quixote, about a nobleman who goes insane and decides to become a knight and revive the code of chivalry even though it was decidedly old-fashioned by then, is best known for its scene, enacted several times in this film, where the Don charges at windmills thinking that they’re ferocious giants; from it stems the phase, “tilting at windmills”. The idea could also apply to director Terry Gilliam, who has at last made the movie he first conceptualised in 1989. He tried to make it in 1998 with Jean Rochefort as Quixote and Johnny Depp as Tony Grisoni the modern substitute for Sancho Panza, but a series of disasters including floods destroying sets and equipment, the departure of Rochefort due to illness, and finnncial issues caused it to be shut down. Not to be defeated, Gilliam attempted to relaunch production in 2008 with Depp and Robert Duvall as Quixote. Depp had to leave due to his tight schedule and was replaced by Ewan McGregor, then funding collapsed. In 2014, Gilliam tried a third time, with John Hurt now as Quixote and Jack O’Connell as Tony, but production was suspended again due to Hurt being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. However, it was fourth time lucky for Gilliam – well, not entirely. He finally got to make the thing, but, due to a lengthy dispute with former producer Paulo Branco over ownership, it had only sparodic and limited releases and didn’t even hit UK cinemas till early this year even though it had been available on disc in some other countries. I held off buying it, because I wanted to experience Gilliam’s new movie on the big screen, but the ‘blink and you miss it’ theatrical release passed me by. The biggest question to this Gilliam lover was, “was it worth the wait”? The answer is a resounding yes.

Saying that, it’s certainly not the Gilliam film to convert dissenters; it’s messy and doesn’t always seem focused, but of course us fans don’t tend to mind that at all and enjoy the way one of our favourite filmmakers likes to go all over the place while insanity continually tries to burst out – yet paradoxically even the films where he’s more reigned in – notably The Fisher King and Twelve Monkeys – remain, somehow, pure Gilliam. What makes this one so fascinating is that not only could you call it the portable Gilliam as it incorporates virtually all of his obsessions and continually seems to semi-refer to earlier work while still seeming surprisingly fresh, but that it seems to be the most personal offering from the 79-year old filmmaker, even coming across as a strange kind of semi-autobiography. In a way like Quentin Tarantino did in Once Upon A Time In Hollywood but less obliquely, Gilliam seems to be looking at himself, his place in the world of movie-making, and his legacy. This made watching it a very poignant experience for me, even though as usual Gilliam avoids sentimentality and maintains a cynical, questioning edge. I’d go to say that the two main characters basically make up Gilliam’s two opposites; Toby, despite being a young man, is the cynical, world-worn filmmaker and even person that Gilliam thinks he’s become, while the ironically elderly Javier is the one who’s young at heart, still dreaming, still tilting at windmills. The two sides of Gilliam seem to be doing battle throughout the picture – and you can probably already guess which one is the victor.

Amusingly introduced with the text, “and now, after more than 25 years in the making – and unmaking”, the film opens with the voice of Javier as Quixote introducing himself over the image of a book, before we see another Quixote charging at a windmill and getting caught up by one of the sails. But it’s not real, it’s a scene being filmed for a commercial by Toby Grummett, who likes his arse to be licked and likes the ladies too, leading to Gilliam doing the age-old scene of a man having to flee from a woman’s place when her husband surprises them; he’s clearly more interested though on the moments leading up to this when Toby’s distracted from having sex with Olga Kurylenko as Jacqui by this film he once made. The clips that we see of Toby’s student Don Quixote film indicate an almost neo-realist vibe, and it’s interesting to see Gilliam try his hand at this style. But when he goes to the place where he shot it, he finds that the film had a negative effect on its two stars. Angelica became a prostitute and moved away despite Toby promising her stardom, and Javier thinks he’s Don Quixote; though to be fair the signs of this are shown in a flashback when Toby casts Javier when he draws his sword to challenge a guy hassling a waitress in a bar. The touch of a woman charging for visitors to see Quixote is a neat comment on greed [I doubt that Quixote gets much of this cash], but what’s startling is the idea that a movie can damage people [or maybe it’s not, considering some of Gilliam’s comments on some of today’s cinema; most filmmakers most tend to express a deep love for the cinema if they feature it in their own films, but not this one.

Toby is thrown into the back of a police car which he amusingly shares with the man whose bike he stole, but Javier soon turns up, intending to carry out a rescue. Soon the two are off into the desert, Javier always insistent that they are Quixote and Sancho, meaning that he’s constantly speaking to Sancho as if he’s an ignorant peasant. He believes that every woman he meets falls for him even though he’s yearning after Dulcinea del Toboso, the lady of his dreams [who’s actually a prostitute in the novel]. He’s also given to self pity, “I’m four hundred years old, it’s not easy living so long but I cannot die”. Gilliam and his co-screenwriter Tony Grisoni are brave enough to admit that the film soon settles into a series of vignettes with the exchange,“Try to keep up with the plot”, “there’s a plot”? – but thankfully the meta element doesn’t turn into smug, “oh look how clever we are” stuff. Fantasy and reality begin to merge as encounters with a decrepit village populated by impoverished people, gold inside a dead creature and the ‘Knight of Mirrors’ have surprising conclusions. While we do see some odd sights such as CG eyes and mouths appearing on hanging bags, and three giants rendered with real performers and model work, large scale fantasy sequences are avoided. This was no doubt because of the fairly low budget, Gilliam having to scale down things from the screenplay that he intended to film. Instead we have a continual playing with what’s real with flashbacks, dreams, and things frequently not turning out to be what we think they are. Some may tire of this; Gilliamites won’t. Even though it’s proceeded by a really clever scene where Javier actually has to play Quixote in public, the climax doesn’t quite work as well as it should, Gilliam struggling to raise it to a higher level despite its length and despite employing lots of the usual fish eye lens shots and Dutch angles which he’d previously skimped on. But this only weakens matters just a little; this isn’t supposed to be an action film, after all.

Of course there’s a love story, here a strange triangle involving Jacqui, Tony and Angelica. Both ladies are in violently abusive relationships and therefore need to be ‘rescued’ – though only one actually is. In today’s climate where such placing and handling of female characters tends to be moaned about, this is pretty brave, but it reinforces the theme of chivalry, where a knight’s dream is to save a damsel in distress, and Jacqui and Angelica are fairly strong characters even if they’re both hard to pin down. Of course the real heart of the story is the relationship between Toby and Javier, much of the humour deriving from Javier’s treatment of Toby with lines like, “such ears, perhaps he caught something from his donkey”, and Javier constantly seeing things wrong, like when he mistakes sheep for, “wise scholars in their robes of white, their heads bowed in praise to Allah”. I think it’s possible to laugh at insanity without feeling at all bad, especially when we also love the character of Javier, and where the ending of the film suggests that, possibly, madness might be the only way to survive this world. Another sheep gag is borrowed from Shanghai Knights. Things don’t get as Python-ish as you might expect, though one duel can’t help but evoke Monty Python And The Holy Grail with the way it looks and is handled, while many Gilliam protagonists, especially The Fisher King’s Parry and Brazil‘s Sam Lowry. are echoed in Javier. Of course it helps that Javier is played by Jonathan Price, the romantic dreamer of Gilliam’s most iconic movie. He throws himself into the part with great energy, clearly enjoying himself immensely; it’s never a subtle performance, but then it’s Adam Driver who has possibly the harder of the two main roles because he has to show a lot of internal change. He continues to impress.

Despite all those resplendent CG scapes in The Imaginarium Of Dr. Parnassus, this is easily Gilliam’s best looking work since Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas, cinematographer Nicola Pecorini doing a terrific job, be it the gold hues of many of the interior scenes, the vistas and ruins of Portugal, or the domination by red during the climax. And Roque Banos provides a fine music score, with a great combination of standard orchestra with regional instruments; though his waltz piece is so much like the second part of Shostakovich’s ‘Suite for Variety Orchestra’ [heard in many films and TV shows from Harry Potter to Batman Vs. Superman to Mr. Robot] one wonders if Gilliam asked Banos to mimic it. It’s fair to say that, if this turns out to be Gilliam’s last film, it will be a hugely appropriate finish, and not just because he’s spent so much of his life trying to make it. From the importance of imagination, to the need for fantasy in a cruel world, to madness, to perception, to the middle ages,; the themes that Gilliam likes to explore and the things he’s interested in are packed into this one, but more than any other of his films [which all feel personal to an extent], it’s foremost about Gilliam himself, and, even if he may had the money to go to town with elaborate visuals if he’d made it earlier, it’s entirely right that he’s mow made it in the twilight of his career and life, because it enables him to be reflective with the wisdom of old age. We’re reminded of how we have youthful dreams which eventually fade to become faint memories in our middle age, yet in our old age we might become consumed by them, for good or for bad. And we’re reminded that, even in our time, we still need people like Don Quixote, people with moral cores and boundless imagination; so what if they may need to reshape reality to fit their circumstances and worldview? The cinema would be a much duller place without Gilliam’s tilting at windmills.

Be the first to comment