Hell Bent, Straight Shooting (1917, 1918)

Written by: Eugene B. Lewis, George Hively, Harry Carey, John Ford

Starring: Duke R. Lee, Harry Carey, Molly Molone, Neva Gerber

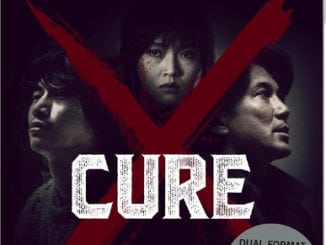

STRAIGHT SHOOTING [1917] and HELL BENT [1918]- TWO FILMS BY JOHN FORD: On Blu-ray 19TH APRIL, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

There was once a time where I wouldn’t have wanted to watch and review almost any John Ford film. But we’re living in a different time now, to the point where I was very eager to check out Eureka’s latest two-fer which is a release of two very early films from him.

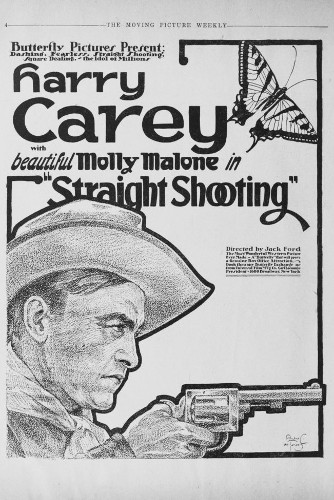

STRAIGHT SHOOTING [1916]

RUNNING TIME: 72 mins

The war between the ranchers and the settlers in the Old West is underway. Outlaw Cheyenne Harry is willing to do anything if the price is right – well, almost anything. He’s hired by his old friend Sweet Water Sims to run off some homesteaders but when he finds the family standing over the grave of a young man who was killed by Sims’ goons, Harry decides to change sides.

Yes indeed, there once was a time when I didn’t rate John Ford – well, except for The Searchers. All that sentiment for a West that never existed, a West which was a lie. And that boozy, Oirish humour. Urgh! Or so I thought at the time. The last few years have had several Ford films come my way due to being a reviewer for this here website, and watching them after so many years with an older and more observant eye revealed a hell of a lot to appreciate – and also maybe that my tastes had changed. Even some of that boozy, Oirish humour was rather appealing. So I was mighty keen to check out these two productions from the silent days, his first and fifth films. While my list of Ford films I’ve viewed gradually gets longer, I’d had no experience of Ford’s work prior to his early classic from 1935 The Informer, and little knowledge of it, so I was going into these almost blind. It’s fair to say that Straight Shooting is not a film that will be enjoyed if you don’t like westerns – it’s a nonstop series of western cliches, but were they cliches back in 1917? Western literature and movie shorts had been popular for some time with a William S. Hart being the genre’s first star, so I guess much of this was familiar to people at the time, but they were still no doubt thrilled to see it all packed into a feature-length movie. Of course there’s some clumsiness, including awkward edits and too many scenes of its hero simply staring into space, but the simple plot is handled with some visual flair and one cannot help but notice some devices Ford will later re-use over and over again, plus some of his familiar interests.

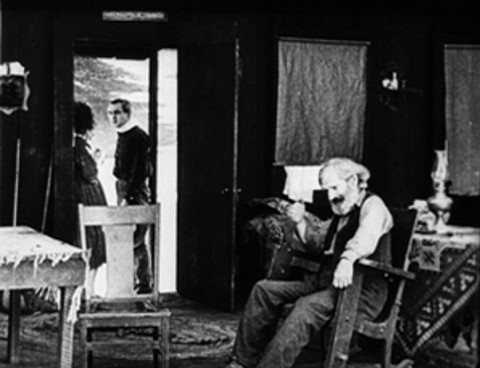

“There was a time when the western planes belonged to no man” begins the scene-setting opening text, and one can only cringe seeing as in reality the western planes most definitely did belong to a certain people. But otherwise this is a not a western worth me getting on my high horse [sorry] about. The first shot of cattle being driven over a hill is followed by an iris introduction to the main villain, Thunder Flint, before the full image returns and we get a terrific panorama of Flint on a hill while hundred of cattle are dotted about like ants way beneath him. As the plot gets underway, the other main players in the drama are then introduced with the name of the person playing them at the bottom. Sweet Water Sims is a settler with a daughter, Joan, and a son, Ted. They’ve just had their water spring fenced off by Flint who wants all settlers in the area to leave. The news is given to them by Danny Morgan, one of Flint’s lackeys, though he’s not that bad and fancies Joan. As he turns up, he’s framed from the inside of a doorway and one just has to grin at the first [unless there are some in his earlier shorts] usage of this visual device that would become a Ford favourite and culminate in the iconic final shot of The Searchers. Flint decides that he wants our hero to help him, so we now cut to a great introduction for him, leaping out from a huge hole in a tree that has a wanted poster nailed to it, grinning like the Cheshire Cat. The Ford celebration of booze is already in evidence in the next scene he’s in where he’s found passed out drunk in the saloon, and then, after Harry has met up with the outlaw gang he has a not totally clear relationship with, he and one of Flint’s men Placer Fremont get plastered together into the same place. They drunkenly threaten someone, can’t catch him when a fight nearly breaks out and the guy and his friend flee, then pull the bartender onto the table and pour a bowl of something over him. Ain’t liquor grand?

Sheriff Connors then shows up and almost arrests the two until Flint also appears and stops him, showing to us that this Sheriff is very ineffectual. Under orders from Flint, Fremont sneaks up on Ted and shoots him in the back, the camera keeping back from the killing which we see it only from Fremont’s point of view, showing, perhaps, that this isn’t a big deal to Fremont. We’re only allowed to get its real impact when father comes across his dead body. Him lying on the freshly dug grave is perhaps a bit over the top, though this kind of thing was unavoidably common in the silent era, and displays of grief can indeed be really extreme so I’m not going to mock it. In any case, we also get a really touching little bit of business when Joan lays her brother’s place at the table and clutches the plate, stuck in a strong wave of grief, a moment that we linger upon as she puts it to her mouth. Much like the perhaps more conventional vignette of the bandit who picks at the inside of a jam jar before taking the thing, it’s a good example of the relatable touches of humanity that would go on to pepper Ford’s films but which many other filmmakers wouldn’t think of putting in. Harry comes across the grieving family and there and then changes sides. It would have been more believable and indeed interesting if the change had been gradual, perhaps if he visited the family a couple more times and each time he was more sympathetic to them. Instead he just says, “I’m not the kind who makes war on old men and young kids” and that’s it, he’s on the side of the angels. Of course he also takes a liking to Joan, and she him, though we don’t get much time for romance. At least the expected conflict between Harry and Danny over Joan doesn’t take place, and we like Danny almost as much and wish that we could get to know his character a bit more.

The action comes in full force in the second half. A duel involving rifles rather than pistols is a bit odd and amusing. The two participants pass each other before looking at each other and then running for shelter. The climactic battle contains some not too fine editing, but then Ford was also clearly still learning his craft. At times it seems like shots could be missing. There’s a strange early scene where a confrontation is brewing in the saloon and then suddenly we cut to an outside shot of two men jumping out of a high window onto a rooftop. Maybe this was a deliberate stylistic device, maybe it wasn’t, though it’s interesting to see an early use of movement around vertical architecture, something Ford would go on to do quite often. We also get some early Fordian landscape shots, particularly of a narrow valley between two cliffs which looks like it was reused in Stagecoach, often with riders standing watch atop the rocky outcroppings at the top of the frame. Characters often have objects placed between them which gives some depth of field, and of course much use of a doorway between inside and outside shot from the former, a simple and un-intrusive symbol for the transition between the wilderness and domesticity. Some more of the short running time is taken by several scenes of Harry pondering. Harry Carey became Ford’s star of choice for a few years after this film. He’s only able to convey depth of thought very superficially, though he does look suitably tough and certainly has a strong John Wayne-like presence. It’s possible that Wayne was inspired by some of his mannerisms and his attitude. By comparison Molly Malone is very lively and rather earthy and the film would have been lifted by her being in it far more. Her cheeky behaviour in the final scene is especially memorable. Also strong is Hoot Gibson, who also went on to become a notable cowboy actor, as Danny. Without any histrionics and some considerable nuance, he shows how his character in torn between his duty and his heart.

The brevity of some of the aspects of the story include the lack of any sort of confrontation between Harry and Sims after Harry has changed, which really is disappointing and almost makes one wonder if some footage towards the end is missing. However, the line of thought from Straight Shooting to The Searchers is extremely strong. I imagine that many studies of Ford’s work do mention it, but I’m surprised that it’s not better known seeing how well known and seen the 1956 film is. We linger during Straight Shooting‘s coda, being made to wonder what the future of Harry will be as he hears, “those little voices that are always calling and calling”, and therefore has to decide where he thinks his place is. Then screenwriter George Hively opts for the more surprising resolution- though I’m probably just saying that because of all these western heroes who remain loners that I’ve watched over the years. The resolution does sort of contradict the scene before it. Nonetheles, despite the things that he’s done, this western hero can still be redeemed and step across the threshold and be a part of civilisation. We’re in a far more innocent time. And indeed if you can put yourself in that mindset of a far more innocent time, there’s a fair bit of fun to be had here. Despite some of the cutting, there were times that you may forgot you’re watching a film that was made in cinema’s infancy over a hundred years ago. I know I did.

Rating:

‘STRAIGHT SHOOTING’ SPECIAL FEATURES

Presented in 1080p on Blu-ray from a 4K restoration undertaken by Universal Pictures, available for the first time ever on home video in the UK

This film was thought lost for many decades until a print was found in the Czech National Archive. Eureka have probably ported over the restoration used on the Region A Kino-Lorber release and given it a new encode. There are the expected examples of print damage, but nothing distracting, and missing frames are surprisingly infrequent. Depth and detail are sometimes quite remarkable, though you can also tell when interior sets have no roof due to the lighting. There’s one strange shot about half way through that I thought was blurry due to damage, but the audio commentary tells that it was intentional for dramatic effect. The final scene looks distinctly poorer than the rest of the film.

Score by Michael Gatt

This piano score sounds entirely appropriate and authentic. Maybe it seems a bit over the top during fast moments, but that’s probably how it would have been.

Audio commentary by film historian Joseph McBride

The author of two books on Ford is hugely qualified to talk about this film, and he discusses it in detail, clearly having enough to say without the need to pad things out with extensive biographies. He’s calm but authoritive as he tells of how Ford made a whopping sixty-five silent films from which in 1967 only twelve existed though it’s now twenty-five, how Straight Shooting was intended as a short but Ford was able to shot more footage when he claimed what he’d already filmed fell into the Colorado River, and thinks the ending may have put together for a re-release. McBride also gives some insight about what the authoritarian Ford was really like and offers a theory as to why he was so melancholic about home and family. Very good, McBride never running out of relevant things to say.

Brand new interview with film critic and author Kim Newman [22 mins]

Eureka have added to the special features on the Kino with Newman in typically enthusiastic, unrehearsed-seeming form. How is it possible to seem so enthusiastic about so many films and so many types of film? Newman once wrote a book on westerns so clearly enjoys talking about the genre’s early days. We learn about Carey and how the “good-bad man changing” premise was frequently in his films, learn that after their falling out Ford seemed to begrudge Carey’s existence until his death when he displayed a lot of reverence for him, and are reminded of how long the archetypal western hero who’s a dying breed remained the most used plot in the genre for so many decades.

Bull Scores a Touchdown – Video essay by Tag Gallagher [10 mins]

Gallagher briefly looks at the very early career of the man who was John Feeney and Jack Ford before he became John Ford, shows how Beale’s Canyon was used in other Ford film and even a Buster Keaton one, and examines Ford’s visual style which is already highly distinctive in this film. There’s very little repeating of other material here

A short fragment of the lost film Hitchin’ Posts [dir. John Ford, 1920] preserved by the Library of Congress [3 mins]

Some gambling is all that survives of this drama set on a Mississippi River steamer.

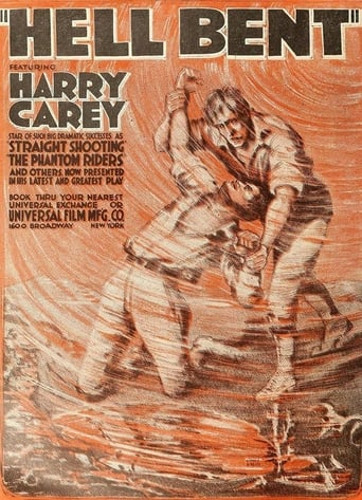

HELL BENT [1917]

RUNNING TIME: 52 mins

Money and gold being transported to and from the town of Rawhide is often intercepted and taken by Beau Ross and his gang of crooks, so cleverer ways need to be found. Meanwhile, after narrowly avoiding being shot when he cheats at a card game, Cheyenne Harry escapes to Rawhide where he falls for Bess Thurston, who’s dancing in the local saloon because her lazy brother Jack has just lost his job and won’t look any other work. He pals up with Cimarron Bill, but it seems to be the vicious Ross who rules the roost in this place….

I expected a film totally unrelated to Straight Shooting, though its basic story of redemption through love is the same, and it actually features the same hero character, one that star Harry Carey played many times. That doesn’t necessarily make it a sequel though. We last left Cheyenne Harry entering into domestic bliss and leaving his old life behind. Here though he’s just got himself in trouble and has to flee to the next county where the law can’t reach him, a situation which we can imagine he’s been in more than once before. So I guess that these films either aren’t in any sort of chronological order at all and exist in different universes, or are a bit like the majority of the James Bond films where 007 ends up with the heroine but is free and single again by the time the next adventure comes along. In any case, Hell Bent, which sounds more like a title for a horror movie nowadays but was probably an obvious one for a western back then, is a somewhat lighter endeavour. It’s also a slightly weaker one, though I’ll be honest and admit that one reason for me that one thing that took me a while to get used to was the amount of missing frames that were in evidence. Obviously this is common with silent cinema so in this case should not at all be considered a flaw. Much footage also seems to be missing, but it’s of course possible that the full version filled in what sometimes feels like the outline of a story rather than a story. Lacking the previous film’s moments of thinking, this one moves at a very fast lick indeed while Ford is again building up the shots, the devices, the situations, he would go on to use again and again in successive films, though the camera is usually able to view the characters without anything partly in the way this time.

Hell Bent has a terrific introduction, even if it does suggest that the whole film is going to be more sophisticated than it actually is, maybe be a precursor to The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and comment on storytelling and legend. A man is sitting on a chair inside his home in front of his fire before he gets up and sits at his writing desk to re-read a letter that’s been sent to him by his publisher’s assistant. “We would like it if the hero in your next story were a more ordinary man, as bad as he is good. The public is already tired of perfect men in novels who embody every value. Everyone knows such people do not exist”. Then he gets up and looks at a painting on one of his walls, Misdeal by Frederic Remington, one of the great western painters. It depicts the end of a shootout inside a saloon, with several bodies on the floor and a couple of scared onlookers. The camera zooms in to the picture [Ford using the zoom lens!] and a dissolve transitions to a real saloon interior and situation that totally replicate the painting, the people suddenly moving as we learn that somebody, who of course has to be Harry, has been in a shootout over a card game, killed a few people and fled. But then we get a somewhat similar transition a bit later when Harry enters Rawhide’s saloon. He does this on his horse, and even rides it upstairs while the camera adopts an elevated [though not aerial] angle. The folk in the bar are standing totally still, then they start very simple movements, then they properly dance! It’s really lovely and nicely done too

Harry gets another good entrance, reflected in a river getting off his horse to drink some much-needed water. He also pulls out a letter and re-reads it: “Harry, stay sober and watch out, the Sheriff’s after you. P. S. the gold is on its way to Rawhide, if you want it”. But Harry has no interest in robbing another stagecoach. A gang does try to do this, but are fooled and find no gold. We’re also introduced to the subplot of Bess and her rather unpleasant brother Jack, she having to demean herself as a dancing girl [and I wonder if prostitute is being hinted at?]. Harry likes her at first and gets a job as a bouncer in the place because of this, but is then put off by her job. Even if she is indeed just a dancer surely Harry has encountered women of lowlier a station, being somebody who’s clearly been around? He’s hardly a paragon of virtue. But then silent films do often display an often contradictory uptight morality that continued for a while as cinema reflected general thinking. In any case, Harry seems more interested in local toughie with a sentimental streak Cimarron Bill, played by Duke R. Lee who had villain duties in the prior film, first attempting to climb into his bed because all the others are full, a situation that Ford would repeat several times in what seems to be a bit of genuine gay-themed humour, as much as they would have allowed back then. After some jokey rivalry, these two bond when they both sing a song named ‘Sweet Genevieve’ together and are soon boozing it up. Harry sees Bess being fought over by loads of other men, rescues her, then tries to snog her, both because of what kind of girl he thinks she is, and the fact that he’s plastered. But she pushes him away, though they make up later and she’s soon serving him, to his consternation, tea [oh the horror!], while the spurned Bill is left to say, “And he was such a good guy to sing ‘Sweet Genevieve’ with”.

Not much action takes place for a while but Beau Ross is hanging around town in disguise and eventually there’s a bank robbery which Harry deliberately fails to stop for a specific reason, though being called a coward by his lady love causes him to regret this, after which he falls for a trick. We’re not particularly surprised when one particular character is kidnapped, though we are surprised when another character is revealed to be in with the bad guys; one would surely expect this admittedly not too nice a person to redeem himself. Of course there’s a small battle, though the editing seems a bit haphazard due possibly to missing shots, and then we suddenly find ourselves in the desert, a scene or two obviously missing inbetween, though it allows for an impressive realisation of the idea of a mirage and a rare Ford foray into the world of special effects. The top left quarter of the frame is taken up by a [very good] matte shot of a desert wasteland which dissolves into one of a pretty lake and house The most exciting bit is when the carriage of a stagecoach falls down part of a hill and is then crashed into by the rest of said stagecoach without a single cut, the camera remaining fixed on the upper road before suddenly dropping down, as if it’s just remembered to do so, to the lower road to catch the action just in time. Of course we get more great landscape shots like a terrific one that looks down into a valley from very high up, the same valley, in fact, seen in Straight Shooting. Unlike in the previous film, only two iris shots appear, and characters don’t tend to have objects in front of them either, but they’re frequently framed by objects, including more of those doorways, if not nearly as many as were in Straight Shooting where it really seemed as if Ford was having too much fun incorporating this wonderful shot and metaphor for one of the essential conflicts in the western genre.

Two Native Americans hang around the town and in the saloon, one of them turning scout near the end. I’d rather there were no Native Americans in the film at all to be honest. Beau Ross is sometimes called Bean Ross for some reason. Joe Harris who plays him makes for a rather unintimidating bad guy; his embarrassed reaction when his identity is discovered is just funny. Neva Gerber does the wide-eyed heroine thing and other cast members tend to be routine, though Carey is better than he was before. Given far less time to muse and more romantic scenes to play, Carey comes off really well, I especially like the way he constantly seems on the verge of leaping into action despite his generally laidback manner, though he actually looks genuinely blotto throughout. Well, he probably wasn’t even the first screen performer to be like this, and I can’t say it affects the quality of his performance. This time we don’t see Harry spending time thinking about where his future lies; the coda delivers a quick, simple romantic finish and a minor laugh. Hell Bent doesn’t really flow and can be frustrating the way that it just provides us with skeletal impressions some of the time, but how much of this is because a substantia amount of footage is missing? I have the feeling that the uncut version would be significantly better if hope that a print may be found of it one day. Nonetheless there’s a lot to enjoy.

Rating:

‘HELL BENT’ SPECIAL FEATURES

Presented in 1080p on Blu-ray from a 4K restoration undertaken by Universal Pictures, available for the first time ever on home video in the UK

Hell Bent looks a bit ropier than Straight Shooting, with more specks, lines and missing frames, though the High Definition at least makes things look very clear

Score by Zachary Marsh

Unlike the piano backing for the previous film, this score is played by a small ensemble of instruments used in the period, so it sounds authentic in a different way. Lighter and perhaps not dramatic enough for some, I still found it perfectly fine.

Audio commentary by film historian Joseph McBride

McBride returns and delivers a talk track with hardly any repetition from his previous one. We learn the outlines of the real reason why Ford and McBride fell out which was based on the spreading of gossip about Ford’s sexuality, that the studios tended to leave the makers of these films alone because they knew what they were getting and they were profitable, and that the reason that Ford liked to have characters enter and exit contradictory sides of the frame – something done a lot here – was to that it was harder for studios to shorten his scenes. There’s obviously even less material available on the making of this film, but McBride never runs of steam and keep things relevant.

Archival audio interview from 1970 with John Ford by Joseph McBride [44 mins]

This is a fascinating special feature, but beware; the elderly Ford is cagey, grumpy and even downright rude, even telling off McBride for asking stupid questions or on one occasion saying McBride to, “try that again, different way, different wording”. Along the way, he also says that Peter Bogdanovich who wrote a book about him is “full of shit” and that he was unaware when he was being interviewed by him, dismisses questions about some of his films with answers like “I don’t know”, and calls a script for a movie he’s trying to set up the best he ever read but doesn’t know who wrote it. There are also a lot of uncomfortable pauses but when, near the end, Ford says that he’s, “sick and tired of answering the same questions” one does sympathise, as well as reluctantly admire him for making it plain that he isn’t enjoying being interviewed.

A Horse or a Mary? – Video essay by Tag Gallagher [9 mins]

A similar video essay to Gallagher’s previous one, tending to repeat things but in the context of this film, though the visual style is examined and it’s nice to see shots of many of the cast members in other productions, some of them sound.

BLU-RAY SET SPECIAL FEATURES

Limited Edition O-Card slipcase and reversible sleeve artwork [2000 copies]

A collector’s booklet featuring writing by Richard Combs, Phil Hoad, and Tag Gallagher

Highly Recommended to western and Ford fans; ‘Straight Shooting’ is virtually a seminal Ford film. Probably not for others though.

Be the first to comment