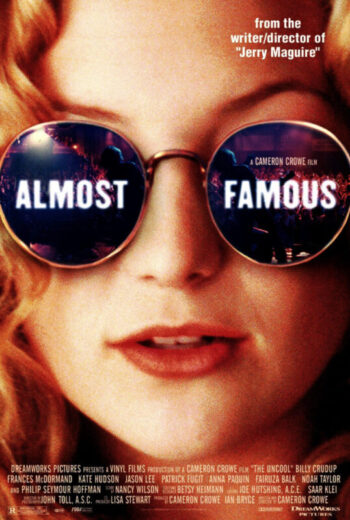

Almost Famous (2000)

Directed by: Cameron Crowe

Written by: Cameron Crowe

Starring: Billy Crudup. Jason Lee, Kate Hudson, Patrick Fugit

ALMOST FAMOUS (2001)

Directed by Cameron Crowe

This feature contains spoilers.

Revisiting an old favourite decades later isn’t always a good thing. There are some I’ll never grow out of, such as Jurassic Park, Watership Down or ET. Others I think may look pretty naff now seem even better: The Matrix, Elm Street 3. But there are times the movie’s language, values, or messages have poorly dated (Silence of the Lambs) or it never was all that to begin with. Then there are ones like Almost Famous that are so intimately associated with a particular stage in one’s life it’s hard to imagine still identifying with it at all. The last time I saw it, I probably wasn’t far off William’s age – I’m mid-thirties now, and likely haven’t seen it since I was 16 or 17. I was equally obsessed with classic rock too (or just ‘rock’ in his day) – and had been since my older brother made me a compilation tape. Back then, my friends and I wanted to be like the guys in the movie: grow our hair long and stay up all night talking about music and drinking – even if they wouldn’t be seen dead in the sorts of old man bars who’d serve us.

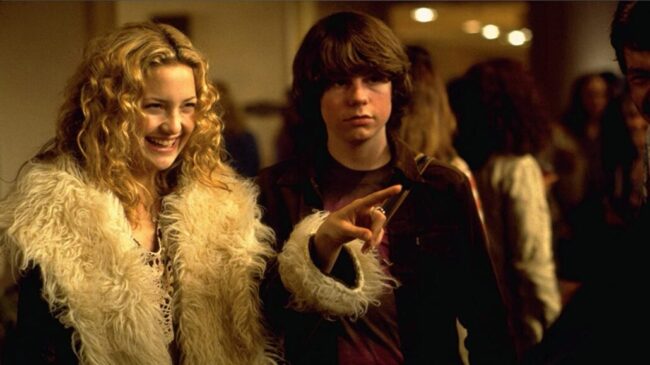

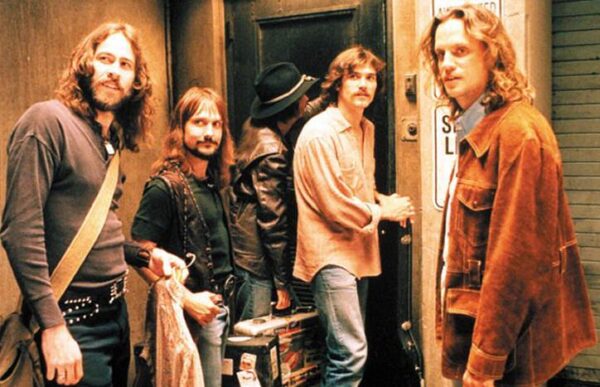

Living out our teenage fantasy is William Miller (Fugit): a wannabe journo mid-schooler who is “too sweet for rock’n’roll”. Not that you blame him – he comes from the sort of household where his ultra-cautious single mum Elaine thinks Simon and Garfunkel are too edgy (all the pot). So one day, he does what they suggest: walks off to look for America. A chat with his favourite critic, the very real Lester Bangs, leads to him hanging backstage with Stillwater (I wonder who they’re based on). As he misses more and more tests, he gets an alternative education from warring bandmates Russell (Crudup) and Jeff (Lee), plus their groupies – who identify as “band-aids”. Lead among them is Penny Lane (Hudson): sexy, mysterious, and capable of lighting up any room she enters. It’s a coming of age that watches like Huck Finn meets Hendrix. Seeing it now, what’s interesting is how little Almost Famous romanticises life on the road. Rather than wanting to be at the centre, now I take it as seeing how the sausage gets made.

Sure, there are moments it really plays to the dream, making me nostalgic for both a period in my own life, along with an era I never experienced. The bit where Anita plays America to her mum still speaks to a yearning to get out and see the world. There’s the elation when the band yells out Tiny Dancer in unison, the stunning scenery, the spectacle of New York City, hanging in the best bars, and endless conversations about rock being something you live rather than listen to. Who doesn’t want the thrill of hanging out by the side of the stage, surrounded by beautiful people, watching the Russell and co rock out? Yet there’s an irony to him and the others insisting ‘it’s all about the fans’ when their relationship will never be one of equals. They don’t want fans; they want fluffers who they’ll gladly chuck under the tour bus when they get bored of them. Stillwater is not big, though they get to act like they are because their groupies (no matter how much they distance themselves from the term) see them that way. As Sapphire says at one point, fandom is “to truly love some silly little piece of music, or some band, so much that it hurts.” As a teenager, the key point that never occurred to me seems to be that there’s almost an innocence about the faith fans have that their idols can use against them. Her’s is far from the only condemnation: Stillwater also gets dismissed as the sorts of people who will “strangle” what their fans love about their music.

All of this would seem to support the thesis of William’s mum: a wonderfully cast Frances McDormand who can barely conceal her distaste for rock. On first viewing, she was another antagonist – a boring, nagging mum who won’t let her son express himself. Yet seeing it older and wiser, she seems somewhat sympathetic. Yeah, she’s conservative and manipulative, but her love for William is never in doubt no matter how many times he calls to say he’ll be back in another few days. She cares about his wellbeing in a way the stars never will. There’s something particularly sad about seeing her attend her kid’s graduation, to applaud his name when it’s said out loud, knowing he’s not going to be crossing the stage. By the family meal at the end, she is undoubtedly changed by the experience of forcing away both her kids. But then so have they. William set out to see the world he thought she was keeping from him but discovered the one she protected him from.

And yet it’s not a conservative film. Elaine may be vindicated by the end, and the rockers learn they’re the assholes, and won’t save the world with their music. Nonetheless, Almost Famous celebrates the art she’s so scared of – with a stunning soundtrack consisting of Led Zepplin, Black Sabbath, and The Who, among many others. The band may be parasites, but the relationship is, to an extent, symbiotic. With them, William goes places he otherwise never would, gets to publish in his favourite magazine, and builds up a lifetime of memories he’d likely never have otherwise. Heck, he may never have the same opportunity. Almost Famous isn’t just about his loss of innocence and his disillusionment with those he idolises. It’s also about a very specific time and place – beautifully captured by the props department. His journey gets played out in tandem with the gradual downfall of rock – when creativity came into conflict with commerce. In that respect, the band’s journey mirrors his: they go out with a naive set of ideals they later compromise. Not that we feel too sorry for them: their constant feuds, infidelities, and betrayals are incompatible with the band of brothers they present themselves as. When it all comes out, in the airplane scene, the only revelation Russell and Jeff get is they’re as bad as each other.

Crudup and Lee play up their parts egos with perfection. Russell, in particular, is obsessed with realness despite aspiring to be an archetype – fighting to be number one in what should be a partnership. On that point, despite only being his senior by a few years, both men ostensibly take on the role of surrogate father figures to William: inducting him into the lifestyle. They will later reject him, as he will them when he learns to be honest and unmerciful. Perhaps it’s depicting another big part of growing up: seeing your parents as flawed. Yeah, we see some progress: the bandmates shake hands and makeup then ditch their plane again for this bus. Russell also finally gives William that interview. Still, one gets the impression this won’t last: the show must go on. William and Penny may get out of it relatively unscathed, but as long as groups like Stillwater exist, then the same exploitation will. So maybe what the movie wants us fans to do is be more like William’s mentor Lester Bangs (the late, great Philip Seymour Hoffman), and love the music more than the drunken buffoons who make it.

Since this movie’s release, there’s been a revaluation of its most iconic character: Penny Lane. Arguably the quintessential example of the manic pixie dream girl, she’s been criticised for epitomising the whimsical, quirky, eccentric, fantasy trope only there to facilitate the male protagonist’s growth. There certainly are moments she embodies the cliche – like her sliding around an empty concert hall, with roses in her hands. She comes to take on a semi-mythical quality, with Stillwater reflecting on how her legacy will outlive all of them. Yet I think this interpretation does both the part and Hudson’s performance a disservice. She has her flaws and motivations – making her a cut above other cited examples, including Sam in Garden State or Claire Colburn in Elizabethtown. She also never teaches William to embrace life: on the contrary, though he’s infatuated by her idealism, he’s also far more aware of Russell’s fallibility. To the extent that she fits the description, that isn’t why people connect with her.

Most importantly, she has her own character journey that revolves around her stepping away from a make-believe role into someone more authentic – with more autonomy. To the extent she fulfills the cliché, she also ultimately undermines it. The last we see of Penny is her going to Morocco. She still stops to pick up her oversized glasses – the life will always be part of her, but thankfully she’s now the one in control. In the same way, rock music will always be a part of my life – even if my days of gigs, extremely mild illicit substances, and all-nighters are a thing of the past. Like William and Penny, I no longer yearn be a rockstar or vicariously become one through others: to use a cliche, more than ever, it’s all about the music for me. On that point, as I write this feature, I’ve got some of the music I grew up with playing in the background. Quite fittingly, one of the tracks was Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black) by Neil Young and Crazy Horse. Rock and roll is here to stay – indeed. If it’s been a while, I say give Almost Famous another spin – the extended cut if you can find it. Heck, it’s old enough to be classic now.

Be the first to comment