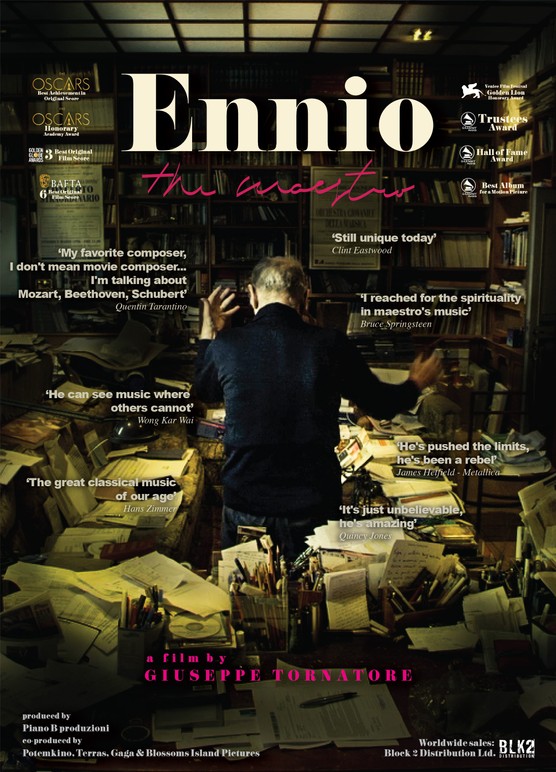

Ennio: The Maestro (2021)

Directed by: Giuseppe Tornatore

Written by: Giuseppe Tornatore

Starring: Clint Eastwood, Hans Zimmer, John Williams, Quentin Tarantino

IN SELECTED CINEMAS

ITALY/JAPAN/BELGIUM/HOLLAND

RUNNING TIME: 156 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

A journey through the life and career of Ennio Morricone [10 November 1928 – 6 July 2020], one of the greatest composers of film music, told largely through interviews with directors, screenwriters, musicians, songwriters, critics, collaborators and fans, not to mention the man himself….

Fans of film music the world over mourned the death of Ennio Morricone nearly two years ago; in fact a great many fans of music in general did the same, which was both pleasing and a little sad, especially to somebody like me who has more movie scores in his music library than anything else, a great many of them of course by Morricone himself. Music written to accompany moving images was generally looked down upon by the snobby classical elite for many decades, with the result that so much stupendous stuff by the likes of John Williams, John Barry, Bernard Herrmann, Miklos Rosza and Jerry Goldsmith, music crafted with care and intelligence that often works well when removed from its primary role while still greatly enhancing the films it was written for, was almost ignored. This was film music, a type of music apparently not deemed worthy of being taken seriously, even [or should that be “especially”] when very popular. Thankfully this has changed a bit in recent years, which provides a nice climax to one of several strands in Ennio, with Morricone’s music being eventually properly recognised by his peers. But then Morricone himself seems to have had a not dissimilar journey. Throughout his life, like many other film music composers he wrote a fair bit of concert music and wished that much more people had heard and appreciated that then a lot of his movie work, and probably even looked down upon his day job during many periods. Yet in his latter years he clearly came to terms with the fact that it’s the immortal soundtracks for the likes The Good The Bad And The Ugly, The Mission and Cinema Paradiso for which he will remain famous.

The collaboration between Morricone and director Giuseppe Tornatore is one of the most fruitful artistic relationships of its nature in recent cinema, so Tornatore was clearly the person to make Ennio, a documentary which is also clearly a very heartfelt tribute to the “The Maestro”. He was able to interview Morricone at great length not long before he passed away, and this reveals a rather different Morricone from the one I certainly had a sense of. Not having yet read his autobiography [I will but I always have a long queue of books to read] which may possibly show a different sort of person anyway, I had a sense of Morricone being rather distant and even “up himself”, even if that in no way interfered with my love of his music and admiration of his genius. Here, we see a somewhat humble, self-effacing man, driven by the idea of achieving artistic heights which I feel he thinks he never fully achieved, but remaining surprisingly down to earth and full of warmth and honesty. We get a sense of his wife Maria’s importance in his professional life, while Tornatore has amassed a great variety of talking heads, from people you may certainly expect [Quentin Tarantino, John Williams] to people you may not [Bruce Springsteen, Wong Kar-Wai], to aid him and Morricone in giving us a potted history of Morricone’s life and career. Alongside this, we have plenty of clips, and not just from movies. Being almost a lifelong Morricone fan, I’d seen some of this material, but certainly not all of it. I grinned from ear to ear at footage of Morricone playing an unused theme from another movie on the piano for Sergio Leone, a theme which then became the most enduring one from Once Upon A Time In America.

Rather than jump around in time, Tornatore prefers to be chronological, and quite often hearing about the early careers of artists we like isn’t particularly interesting; we tend to want to hear about the stuff that we fell in love with and skip beginnings. Not so with Morricone; we’re fascinated by how he arranged loads of pop songs, often in an innovative way though rarely getting credit, and we never lack for suitable footage either. Attending Rome’s Santa Cecilia Conservatory would see him training under the respected teacher and composer Goffredo Petrassi who would strongly influence him for what seems like forever, despite the first major turning point in his career being when Petrassi scored 90% for a piece written for a competition but Morricone scored 95%. Working with an avant-garde collective inspired by John Cage allowed Morricone to develop his creative inventiveness, in particular in using sound effects, but the bread and butter came from song arranging until, after scoring a few minor films, he met Leone, and both realised that they’d been schoolmates. Leone loved a Mexican-themed piece written by Dmitri Tiomkin for Rio Bravo and wanted it in the score for A Fistful Of Dollars, but Morricone, who – as we hear several times – hated incorporating music from others, managed to write an imitation of the track which satisfied Leone. Even though it’s still some of his most popular work, including with Yours Truly, Morricone has always seemed to look down upon his “spaghetti western” music, seemingly because he thinks that it just isn’t very good, and maybe because he got fed up with being asked about it when he’s done so much in nearly every single genre. Morricone and the directors concerned tell of two occasions when two filmmakers – Oliver Stone for U-Turn and Quentin Tarantino for The Hateful Eight – asked for music that recalled the western scores and received something different.

Even though Dario Argento gets to say a few words, many fans of Morricone will be disappointed that Tornatore spends very little time on his giallo period of the late ’60s/’early ’70s, where he composed some of his most extraordinary music, often with a core group of musicians whose contributions to some of these scores has often been ignored. In fact, in sidelining Morricone’s work in cinema of the more exploitative kind, Tornatore sadly betrays a certain snobbishness. Even though this doesn’t stop me from loving his work and considering him to be one of the best and most under-appreciated directors around, it’s a bit of a shame. Whatever you think of these films, Morricone often seemed to relish the opportunity to write music for them, and was particularly effective in musically depicting madness and fear, often in a very experimental and advanced way. Tornatore prefers to spend time on loftier fare, and even films many won’t have heard of; some of them I only knew of because I have some tracks from them on Morricone compilation albums, and three I didn’t know at all. Saying that though, if watching this makes a few people check out the borderline obscure but brilliant The Desert Of The Tartars, then that’s a good thing. And many of the popular scores are certainly covered, even though everyone will no doubt have their favourite which doesn’t appear. I missed the absence of The Thing and was disappointed that A Fistful Of Dynamite, which contains my all-time favourite Morricone piece, was only very briefly referred to. But in the end Ennio is already pretty long at just over two and a half hours and couldn’t cover any more without being even longer. As writer-director Tornatore had the right to select the scores he felt were best or most important, though I do wish that he’d let some people speak for longer than he did. Modern documentaries seem to feel a need to be fast paced, but this doesn’t always allow one to be fully immersed in a subject.

We have a lot of great stories, some of them from Morricone himself. There’s the one of how he was recording the music he’d written for The Cannibals while he was starting work on Burn!. The latter’s director Gello Portovelli heard a piece written for the other film, stole its recording and placed it upon the climax of his own movie, then insisted that Morricone use it. True to his convictions, Morricone refused and just wrote a similar track. We hear of how Leone, for reasons only known to himself, prevented Morricone from scoring A Clockwork Orange by saying he was too busy, which was a lie. How Brian De Palma chose, out of six themes, the one Morricone liked least and told him not to use for The Untouchables. How he thought that The Mission was so powerful it didn’t need any music. How his father lost his skill in playing the trumpet, causing Morricone to not use trumpets in his work until his father passed away, one of several stories that are quite emotional. We even hear the elusive Terence Malick talk about working with Morricone on Days Of Heaven. Sometimes he even tells us how he struggled to find the right musical approach for a film. Two of his major musical collaborators – Alessandro Alessandroni [various instruments especially the guitar] and Edda Dal’ Orso [that haunting wordless female vocal] have things to say. This is all great stuff, and when we go on to folk not connected with Morricone professionally their comments seem honest. I’m not a Hans Zimmer fan for several reasons, but he’s always seemed genuine in his praise of other composers. Yet Ennio seems to struggle in its last half hour. Throughout, the talking heads have been interspersed with movie clips and concert performances in a well organised manner, and there are a few superbly put together montages of single films, but towards the end we get too many concert clips and, even if one accepts that this is a love letter as much as anything else, too much adoration as Tornatore tries to take things to an emotional climax like most of his movies but stumbles somewhat. It doesn’t seem very appropriate either, as Morricone was essentially a low-key personality.

Of course we get to hear lots of Morricone music, though even these small passages sometimes contain awkward edits. The biggest surprise is Tornatore himself. One might expect him to talk about some of his many experiences of working in Morricone in detail. We don’t get any of this at all, which is rather disappointing. Yet one can also admire Tornatore for displaying a humility and integrity here that Morricone would have greatly appreciated, for stepping back and letting others do most of the work, yet the result still exudes his passion for the subject. This means that Ennio is still generally a success, if not quite a production that should be ranked among Tornatore’s very best work. Even though its pacing is very even, I have the feeling that there’s a lot of material that he didn’t use, and I wouldn’t be surprised if, like several other of his films, there’s a longer cut which not just contains much of this deleted material but corrects some of its issues. But in the end we now have a documentary about one of the greatest composers of the 20th [and part of the 21st] century – and that’s a real cause for celebration. It’s almost enough for us not to be too sad that Leningrad, a film that Leone wanted to make with Morricone as the composer, and that Tornatore also wanted to make with Morricone as the composer, will never get made now unless Tornatore decides to use somebody else to do the music – which I can’t see him doing as it would be so very wrong.

Rating:

Be the first to comment