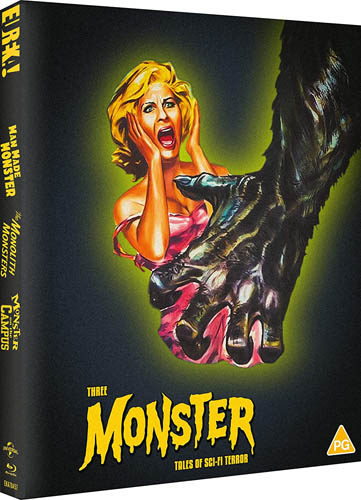

Man-Made Monster, Monster On The Campus, The Monolith Monsters (1941, 1957, 1958)

Directed by: George Waggner, John Sherwood

Written by: David Duncan, Harry Essex, Jack Arnold, Len Golos, Norman Jolley, Robert M. Fresco, Sid Schwartz

Starring: Anne Nagel, Arthur Franz, Grant Williams, Joanna Moore, Judson Pratt, Les Tremayne, Lionel Atwill, Lola Albright, Lon Chaney Jr.

THREE MONSTER TALES OF SCI-FI TERROR

ON BLU-RAY NOW, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

Eureka bring us three old science fiction horrors from Universal, none of which I’d seen before. So do they easily make the ‘B’ grade, or are they better off classified as ‘Z’ movies?

DISC ONE

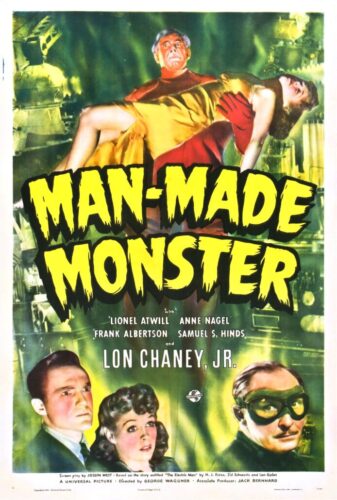

MAN-MADE MONSTER [1941]

RUNNING TIME: 59 mins

“Big Dan” McCormick does a sideshow exhibit as Dynamo Dan, the Electric Man where he places his hands into electrical sockets. This allows him to build up a resistance to electricity. When a bus crashes into power lines, he’s the sole survivor. Distinguished elector-biologist Dr. John Lawrence wants to study him and McCormick goes to live with him and his daughter June. However, his assistant, Dr. Paul Rigas, is secretly conducting experiments to prove his theory that human life can be motivated and controlled by electricity. And he persuades Dan to submit to tests, where Dan absorbs increasingly powerful charges until he develops an amazing degree of immunity. However, he also becomes addicted to the charges and more and more like a robot….

The premise of the executed prisoner, preferably though not necessarily killed on the electric chair, returning from the dead to conduct vengeance became rather popular following the release of Shocker in 1988 which led to a mini-cycle of similar stories [my favourite of which is Prison] and even a few stragglers later on, though there were several much earlier films which employed the idea, the first of which was probably 1936’s The Walking Dead. It’s used in Man-Made Monster too, and to very good effect, though only makes up the final ten minutes of a film which runs one minute less than an hour. This means that you could justifiably say that this is a film which is nearly all preamble and not nearly enough payoff, with only one thrill until its title creature does indeed return from the dead – or rather he never dies at all and being electrocuted as punishment for committing a murder first of all fails to kill him then makes him stronger. I envisaged a film that was of two halves and had its second part be much more developed. Yet despite this structural flaw which means that for much of the time we’re just watching dialogue, there’s considerable involvement in what’s going on due to the brisk storytelling, some good dialogue from screenwriter Joseph West – who’s actually director and producer George Waggner – expanding a short story by H. J. Essex, Len Golos and Sid Schwartz, and a pretty strong performance by Lon Chaney in what was his debut for Universal; it’s small wonder that he was then cast as The Wolf Man seeing as that character was also a sympathetic monster. The film was almost made four years before with Boris Karloff in the Chaney role and Bela Lugosi in the part played by Lionel Atwill. They would have been great and as I began to watch I had visions of myself wishing that they’d done it, but after a while I was pleased that instead I was watching Chaney and Lionel Atwill doing one of his best mad scientists turns.

The title should really have a hyphen in it, and sometimes it does, but not on the opening credits or some of the posters. We don’t actually see Chaney in his character’s first scene where he’s on a bus which skids and crashes into a pylon, via model work which is obvious to our eyes yet which is still quite good. A radio news reader tells of his amazing survival while the five other passengers were all killed. In hospital he’s visited by Dr. Lawrence and tells him of his job as a “yokel shocker” doing “stuff to fool the peasants”, which may not endear him to some viewers, though I wonder if was just trying to impress Dr. Lawrence and doing it in a cack-handed way. A good example of this film’s considerable economy of storytelling is when the doctor hands McCormick his card and tells him to visit him” some time”. We cut to a close-up of the card with his name and address on it, then to an entrance to a house with the same address on it which the released McCormick will visit two scenes after. That’s the odd thing about this movie; while little exciting happens for some time, the thing still moves very fast and at times we could possibly have done with seeing some things that we just hear about, such as McCormick in his role as circus performer, putting his hands into sockets. Lawrence is at home with his daughter June, and McCormick takes a shine to her, though oddly this element remains undeveloped. When June is romanced by another, we expect a scene where he sees the two of them together and is very jealous and angry, yet said scene fails to materialise. This means that when McCormick does what so many monsters of the ’40s and ’50s do and carry her off, it doesn’t entirely makes sense – though of course this can also be said about some similar kidnappings so I guess it’s not a major issue.

Lawrence is a kindly man who wants to do good, but the same cannot be said about his assistant. Lawrence silently observes Dr. Rigas at work and is not pleased with what he sees. “This thing of yours isn’t science, it’s black magic”! he understandably cries, but Rigas goes on about creating a “race of superior men” [a popular goal of screen mad scientists for many decades] where “non entities will be of more use”. I always enjoy the scene where a loony doctor explains not just his plan but his rationale, and the one here is a doozy, with Atwill, whose introduction replicates his one in Doctor X, very much in top form. McCormick is soon living in Lawrence’s house, but is soon being tested in a way that Lawrence would not have even considered. There’s a very well played little moment when McCormick first gets onto the testing table and first smiles, then displays worry and even fear. But soon, as Rigas writes in his diary, “the subject is slowly but surely coming to depend on the doses of electricity”. In between, he’s a shell of a man who comes in to sit at the dinner table, says he isn’t hungry, then walks out of the room, all in a rather zombie-like manner. Eventually a murder takes place and Rigas ensures that he’s convicted; very good is the scene in the courtroom where he gets him to admit to the crime while he calmly sits back and a streak of light moves across his face, suggesting his calculating evil. He wants to see what will happen when he’s on the electric chair, and what might have been the most dramatic scene in the film we just hear about, though this was because the MPAA didn’t allow the sight of an electric chair. The climactic mayhem is nicely staged and manages some pathos, with McCormick not intending to do much damage or harm at all while the special effects of John P. Fulton, which have the rubber-suited McCormick all lit up while his hands and increasingly dessicated head look separated from his body, are of quite a high quality considering the meagre budget.

The romantic interest [if the word “interest” is appropriate seeing as this is often the least interesting material of these films] is carried out by June and a reporter named Mark Adams, a pushy type prone to the odd wisecrack who we often see in films of this time. Such characters I personally often find rather annoying, but he’s certainly given some good lines [of Rigas, “I bet he spent his childhood sticking pins in butterflies”] and it’s really June who the brighter of the two, realising that something’s wrong very early on while Adams dismisses her fears for quite a while. Their developing relationship, which of course begins with her playing hard to get yet not long after that they’re suddenly engaged, is only sketched and therefore doesn’t really convince, but then we don’t want too much time spent on it do we? In any case, we actually care more about McCormick’s relationship with Lawrence’s dog. The two immediately take to each other, but the dog doesn’t like the laboratory which McCormick goes into, and after the latter’s first test is reluctant to come to him when called. This subplot has an appropriate conclusion by which time we are a bit touched. This is largely because of Chaney, mostly photographed of course from his left side so we don’t see much of his large mole on the side of his nose which is also in shadow in some shots, with his underplayed sense of vulnerability pathos despite his immense size and strength which had already served him well in Of Mice And Men. He’s unusually happy go lucky in his early scenes which of course makes his transition all the more powerful.

Director George Waggner does what he can with the very basic sets and lopsided story that sometimes jumps ahead, which is mostly to bring as much pace as he can, while cinematographer Elwood Bredell uses shadow fairly creatively at times, suggesting that this could have been a quite stylish looking film if there had been able to have more time spent on it, despite a general avoidance of the Gothic. Hans J. Salter’s music score is a solid effort with some good dramatic set pieces, though the motif heard over the opening credits that suggests the tale’s essential tragedy isn’t employed again. Some stalking music turns up towards the end which will be very familiar to fans of Universal horror; it was first heard in The Mummy’s Hand then turned up in all the sequels plus a few other films. Also familiar are some pieces of laboratory equipment, though except for a few shots from one or more of the early Frankenstein films where a brick wall is suddenly visible, these seem to be new bits that would then be re-used in successive horrors. All in all this essentially fairly minor cheapie is much more fun than it maybe sounds, with just about enough of that classic Universal horror feel to keep fans occupied.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

Audio Commentary by author Stephen Jones and author/critic Kim Newman (2022)

The Scream Factory Region B releases of these three films all featured audio commentaries; Eureka replace them with other commentaries and I bet your life that they’re superior. For this one, the great pairing of Newman and Jones continues with no abating of enthusiasm. Their tracks for the Indicator releases of La Llorona and The Phantom Of The Monastery almost hit a high, but this one, where they admit they have to talk fast because of the film’s short running time, is no slouch, even though Jones reckons that the bus crash is stock footage; surely it’s model work except for one brief close shot of the bus? The general sadness of Chaney’s career, tarnished by alcoholism and where he was slung into parts that Karloff would have been above taking, is describe, while we also hear about why Atwill’s career suddenly went downhill; he held a sex party but was convicted for perjury when he denied having it. Of course there’s much commentary on the film itself which they both really enjoy; Newman thinks that a burning cart is serial footage while Jones reckons that one murder was altered to just a scare.

Production Stills Gallery

Artwork and Ephemera Gallery

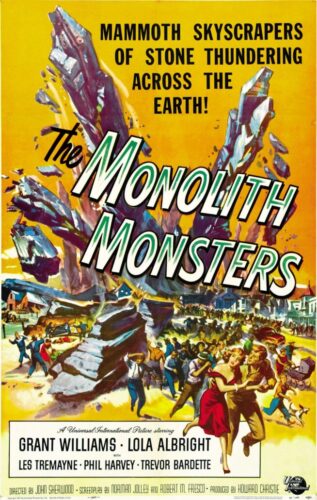

THE MONOLITH MONSTERS [1957]

RUNNING TIME: 77 mins

A meteor lands in the desert near the town of San Angelo, California. Geologist Ben Gilbert finds a black rock and brings it to his office. However, it has a chemical reaction with rain water and next morning Ben is found petrified in the office by his co-worker Dave Miller. Meanwhile Ginny, a pupil in Dave’s girlfriend Cathy Barrett’s school class, takes a piece of meteorite home from a desert trip and is later found in shock with one hand turning into stone, two dead parents and a destroyed farmhouse. Dave seeks out his former professor Arthur Flanders to help him to solve the mystery while Ginny is taken to a Medical Research Institute in Los Angeles to the famous Dr. Steve Hendricks to try to find the cure….

It’s s premise which is both very cool and rather stupid, yet on balance wins because of its simplicity and its difference from your average ’50s sci-fi menace. A strange black meteor crashes and litters the countryside with fragments. When exposed to water, they grow into skyscraper-sized crystal monoliths resembling the crystals that Superman’s Fortress of Solitude is built from. They then topple and shatter into thousands of pieces that grow into monoliths themselves and repeat the process. Anything underneath them is crushed. It’s almost elegant. But, even if you agree that said premise ought to make even a terrible film worth watching, is the sole film [why hasn’t there been a remake or a variation?] it’s in much good otherwise? Well, it virtually follows the generic template for the ’50s American monster movie to a tee. The menace first appears in a strange form that leaves victims mysteriously dead and baffling clues. The scientist or journalist-who-may-as-well-be-a-scientist, assisted by either a patient girlfriend or a lady he’s trying to romance, eventually discovers the real truth of the menace just as it’s about to leap to a new level of terror and danger and we finally get some of the big scale thrills the film’s poster promised. And he’s also able to discover, by combination of quick thinking and good luck, the means to stop them, but will the authorities cooperate and will be be in time? By 1957 all this was probably getting rather tired, and The Monolith Monsters veers close to getting bogged down in scientific chat and laboratory work when what’s going on nearby outside is what we really want to see. But the first and final third come off pretty well and the special effects are really good – the kids shouldn’t chuckle at this one.

These films often begin with some narration over stock footage. Here we have the familiar voice of Paul Frees informing us about meteorites while we’re in space getting a bit closer to planet Earth while meteorites whizz by before we cut to the desert and what’s basically a sparkler heading for the camera before we cut to it crashing over the horizon. The shots are rather familiar, now where have I seen then before – oh yes, it’s the opening of the similarly desert-heavy It Came From Outer Space, though there are tiny differences indicating that we’re seeing alternative takes. So technically we’re not seeing recycled footage, though you could also make a good argument for saying that we are. The narrator gets increasingly portentous, finishing with, “Another strange calling card from the limitless regions of space – its substance unknown, its secrets unexplored. The meteor lies dormant in the night, waiting!” The next day, geologist Ben Gilbert stops his car to sort out its engine and finds a black rock which heh takes to his office where he and local newspaper publisher Martin Cochrane, who complains that “nothing ever happens around here” examine it. That night, a strong wind blows over a full water container onto the rock, starting a strange reaction. When Dave Miller, the head of San Angelo’s district geological office, returns from a business trip, he finds Ben’s corpse in a rock-hard, petrified state and the office’s lab damaged by large rock fragments. Even eerier is the case of little Ginny who’s mother won’t allow the rock that she finds inside her house. Ginny washes it in a large tub outside, and is then found in a catatonic state with her parents dead amidst an entirely wrecked house; one is reminded of the opening of Them! with its terrified little girl only able to cry “them, them!”. Ginny is slowly turning to stone Dave’s girlfriend, her only hope lying with identifying the black rock within eight hours. Dave, his teacher Cathy Barrett and his old college professor, Arthur Flanders, spend a lot of time trying to work out what they’re dealing with.

Indeed a bit too much time is spent on this – we want to see a scary encounter or two with deadly rocks in the desert, darn it. It doesn’t help that soon after we hear of rocks crushing telegraph wires and livestock but don’t see it. Still, I guess it’s good to know what we’re dealing with, even though an element of mystery is rarely a bad thing. The rocks came from a meteorite and drain something from everything they touch, including people, which turns out to be silicon, a substance which in humans it is normally just a trace element but could be existing in the human body to maintain human tissue flexibility. The meteorite’s absorption of silicon was the cause of the deaths and Ginny’s state. Steve then prepares and administers a silicon solution injection to the girl, which is quite shocking really; he does it without any familial or professional authority! You just know what the follow-on scene a bit later is going to be, but it would have been better if tragedy had resulted from such unthinking rashness. Returning to the desert, Dave and Arthur trace the fragments to the crashed meteor and deduce that its atomic structure has been radically altered by the intense heat of atmospheric friction, though of course water is the real culprit, and a full-blown rainstorm is now in progress! Power may go off, things are getting really bad, and Dave and Arthur struggle to find the correct formula. Again, there’s a bit too much time spent on the latter, especially when the eventual solution is so simple, the only thing they haven’t tried yet but it might just work! “Will it stop the monolith”? “it’s like another laboratory experiment; in science, there are no guarantees”. The climax neatly refutes an earlier claim from Martin that the region’s salt flat was “Mother Nature’s worst mistake”, pointing out, ironically, that this near-disaster has just proved otherwise. I’m not going to give everything away, but it’s quite a nice little spectacle with only one stock footage shot.

There aren’t many scenes of the crystals in action, but the ones that we do have come off very well. After we’ve seen small rocks grow, our first glimpse of the much larger variety is in the rainstorm, three tall black rocks looking very ominous. The crystal versions are seen several times in the distance approaching the town, which is a shot of Universal’s familiar small town set partly surrounded by matted desert and mountains, meaning that we’re seeing two kinds of special effects in the same shots almost seamlessly combined together; much praise is due for Clifford Stine here, who had to work on a pretty low budget as was usually the norm for these things. The sole major destruction sequence is when the towers crash down on a miniature farm which looks like it could be the one from The War Of The Worlds, but it’s generally so well executed that we can overlook that something is mysteriously unharmed; watch the scene in question carefully and see if you can spot it! I don’t say this with any element of mockery or spite by the way; I love old school special effects and wish that modern films would use them more, if in conjunction with the CGI that’s not obligatory though isn’t always as convincing as all that. Anyway, I digress. The shots of the real desert may seem familiar because the Alabama Hills in Lone Pine, California, were used in a great many films from 1939’s Gunga Din to 2000’s Gladiator. We don’t get much of a small town feel, but then a lot of the film takes place in the same few interiors. Characterisation is generally set aside for the minor characters; we remember the likes of a stubborn switchboard operator and a boy who won’t help out for nothing. Even the romance is barely there, despite being given a sweet introduction by Ginny who asks Cathy why she won’t marry Dave, suggesting that we’ll later get a proposal scene – though we don’t.

Acting does the job but can only do so much with such thin characterisation, and we can just about let Grant Williams [Dave] off as he’d just been in The Incredible Shrinking Man which was not just a stone-cold classic but a film in which he gave a very strong performance. Jack Arnold co-wrote the story with Robert N. Fresco upon which Fresco and Norman Jolley’s script was based, and one kind of wishes he’d directed too, because John Sherwood, while he does a totally professional job with no real issues, doesn’t make as much out of the desert setting as Arnold did in three of his films, though there’s still an undeniable atmosphere at times when the story ventures outside the two main interior settings. Joseph Gershenson’s musical score underlies every moment, with very loud chords for the black rocks in the early scenes just before a scene transition and even some chirpy then plaintive scoring for Jinny, probably the character we most care about even if she’s not around towards the end. Though a bit static, The Monolith Monsters still has distinct worth for its unique monster and almost being the perfect example of the archetypal ’50s creature feature despite said monster’s uniqueness. And there’s a certain charm to its dated attitude to problem solving, where seemingly bonkers plans are easily carried out with ease which today red tape would all-but forbid; at one point the police immediately approve something that will destroy something which is critical to the town’s economy.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

Brand New Audio Commentary by film historians Kevin Lyons and Jonathan Rigby

Lyons and Rigby are just as welcome as Jones and Newman on these things, and here offer a similarly balanced view of the film in question, as well as reminding us of certain wider things such as that so much of ’50s American cinema was about conformism, which is quite astonishing considering the number of fine films made. The turning to stone element is rightly mentioned as being seemingly important but then peripheral in the second half, though I don’t see the general concept as being as flawed as they claim. Rigby quotes from the press book which tries hard to make the rocks seem terrifying, while Lyons mentions the other two special effects artists who aren’t credited and even disputes Arnold’s involvement.

Production Stills Gallery

Artwork and Ephemera Gallery

Theatrical Trailer

DISC TWO

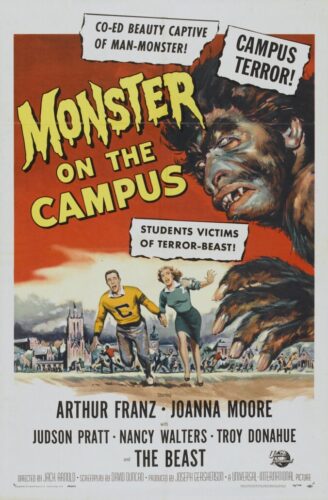

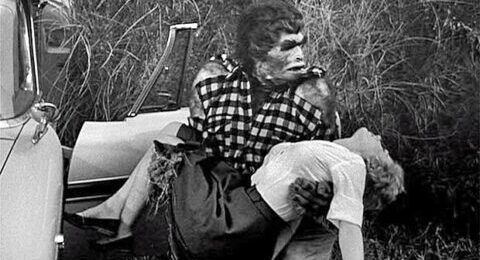

MONSTER ON THE CAMPUS [1058]

RUNNING TIME: 77 mins

At Dunsford University Biology professor Donald Blake, who’s engaged to Dean Howard’s daughter Madeline, receives a coelacanth, a species of fish that’s millions of years old, from Madagascar. Water dripping from its tank causes a dog to regress to its lupine ancestry and turn vicious, then Blake cuts himself on one of the coelacanth’s teeth and is taken to his home by nurse Molly Riordan, where he passes out. There, she’s attacked by somebody and is later found dead by Madeline with Blake’s tie clasp in her hand. Blake admits that he remembers nothing, fingerprints don’t match and the police think that someone is holding a grudge and trying to implicate Blake in Molly’s murder. Yet this someone soon reappears, a someone who seems to resemble a prehistoric man….

Said director Jack Arnold of Monster On The Campus: “I didn’t really hate it, but I didn’t think it was up to the standards of the other films that I have done”. Indeed it most certainly isn’t up to the standards of the likes of The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Creature From The Black Lagoon and even Tarantula, but I don’t think this film is as anonymous and uninteresting as seems to be the critical norm, with Arnold clearly trying to do his best with the material. Out of the three films in this set it’s the most thematically intriguing, is the most atmospheric and is even the most frightening, even if the low budget hampers it rather more than the others. It seem to be a semi-remake of The Neanderthal Man from three years earlier, while you could lay a claim for 1980’s far more elaborate Altered States partly being a remake. What it isn’t is a particularly teen orientated picture despite its title which gives the impression that it’s one of many films of the time aimed principally at the drive-in crowd; of course there are teenagers but they aren’t the main characters. David Duncan’s screenplay goes to bizarre lengths to get our hero re-infected all over again while still being unaware of what’s happening, though really he should have realised early on anyway, making him one of the more stupid screen scientists of the time. Yet this verges on becoming genuinely thought provoking, as if Duncan got carried away then remembered the sort of film he was scripting.

The titles take place over an ominous photo set at night with a tree on the right hand side and the shadow of some creature on the left. The happiness of somebody picking up his dog changes when we cut to Blake’s laboratory and pan along a series of busts that show the evolution of mankind. “Modern Woman” is missing, but Blake has just finished making a mold of his fiancee Madeline’s face to use for that. “Unless we learn to control the instincts we’ve inherited from our apelike ancestors, the human race is doomed”, says Blake depressingly, thereby summing up the main theme in a nutshell, a variation on the the much more common “be careful of so much progress”, suggesting that it’s more within ourselves to sort ourselves out instead of blaming it on progress. His delivery [from a certain Professor Moreau of Madagascar no less for those who would pick up on such things] of the coelacanth [these really do exist] starts to thaw out and first infects the dog who suddenly sports fangs – Blake having to point out to people but which are probably visible from a considerable distance – and a vicious nature, and thereby has to be confined to a cage. It can’t be rabid surely, because there’s no frothing at the mouth? And in a while it becomes normal again which confounds people even more, though I’m jumping ahead a bit. Blake cuts his hand on the coelacanth’s mouth and inadvertently slips his hand into the holding tank water – then what does he do? He sucks the blood off his hand until told not to. But then he rarely seems to be on the ball so it’s probably in character. At Blake’s home, we get the first scene of horror where Molly, the nurse who rather likes him [Madeline asks him later whether they were ever an item and his answer convinces her but not us], is in a room and behind her a door opens before a close-up of a huge monstrous hand and a shadow falling across her face while she screams at what she sees. This is followed by a great moment where Mr. Townsend the night watchman finds Dr. Cole on the ground and bends over to attend to him while behind we see Molly’s body hanging from a tree above him, looking grotesque and even with some blood on her neck.

Even though evidence points to Blake being the culprit, there’s the small matter of mismatching fingerprints, and an autopsy reveals that Molly died of fright, which is quite something considering the nature of her death. Sgt. Mike Stevens and Sgt. Eddie Daniels think that somebody is trying to set Blake up and even give him a bodyguard in the form of Daniels. In his laboratory, Blake shoos away a dragonfly that lands on the coelacanth, but it later returns, now grown to two feet in length. When Blake stabs it, the….actually I’m not going to tell you what happens next because you will more enjoy the ludicrous set up for Blake to change again which I’m surprised didn’t give the film some kind of cult status a decade or so later when “head movies” were becoming popular. Likewise, the explanation for these changes is hard to swallow, even in a film like this. Apparently if blood plasma preserved by gamma rays gets into the bloodstream of an animal or person, it causes them to temporarily revert to a more primitive state. But then this film is set in a college where everyone seems amazingly relaxed despite the reports of a dangerous, beast-like person roaming around. Where its hero leaves a fish to thaw out in the open. And where people often use a door with a USE OTHER DOOR sign on it. It’s really quite peculiar at times. There’s a solid build up to a climax, then what seems to be the climax which is okay if decidedly low key – there’s unfortunately no big rampage through the college which is what you might expect. We seem to be getting our conclusion, but then we get a second climax which seems rather rushed, though there’s a great shot of the shadow the monster approaching somebody while the camera is up high so the shadow is upside down, and we do still feel some of the necessary pathos.

There’s a pretty brutal death for the period with an axe in the face, while this monster clearly has rape on his mind twice. With the exception of his hands and a few long-distance shots, the monster isn’t seen until near the end, which is probably just as well seeing as the mask, a very poor effort by Bud Westmore resembling the 1953 Mr. Hyde, is very stiff and plastic-looking, but then the scarcity of money is visible throughout, notably the sets; even the interior of a log cabin isn’t really satisfactory. Arthur Franz as Blake doesn’t play his alter ego, it’s stuntman Eddie Parker, who seems to be having fun being asked to behave like an ape-man, though of course he’d already played a few other monsters too including the already mentioned Mr. Hyde to Boris Karloff’s Dr. Jekyll. The transformations that we eventually see are decently done, the dissolves almost entirely matching which isn’t always the case, but it’s an earlier change that we don’t actually see which makes the most impression; we adopt the viewpoint of Blake facing the dragonfly and get a sense of his blurry vision before things become clear and we see the ape-man’s huge hand enter the frame and smash the insect in front of him. Such moments indicate that Arnold was attempting to do decent work even if his heart doesn’t seem to be have been wholly in it. And the script does seem to ask questions like whether separating the monstrous from the human might be a beneficial thing ala Robert Louis Stevenson, and maybe be even looking at the subject of conformity [Lyons and Rigby were probably right then], though it seems to condemn both the conformity of the stifling college more interested in publicity than furthering science, and individuality equally.

So it’s all a bit depressing and even nihilistic if you think about it, even if the tone isn’t especially dark despite Russell Mety’s cinematographer sometimes verging on full film noir in style. The sole humorous bit is where teenage couple Jimmy Flanders and Sylvia Daniels are watching the dragonfly [which doesn’t look bad when eventually seen] and they take the opportunity to have a little necking. We see a hand stretch out of the bushes behind Sylvia and clasp the top of our head, though her fear turns to amused surprise when another couple reveal themselves; one wonders what that other couple were actually doing. Troy Donohue and Nancy Daniels are okay as the pair but fill little function except to suddenly show up to reveal something to someone that they should really have revealed earlier but for the script, while Franz is quite likable despite the idiocy of the character he’s playing and Ned Land is an unusually mature heroine. Whit Bissell’s character seems to be set up as a nasty person who we’ll enjoy seeing killed by the ape-man, but it never happens. Music composer Joseph Gershenson requires goes to town with this one, with some especially exciting music towards the end, though maybe not enough emotion. Monster On The Campus is generally a bit better than its reputation.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

2.85:1 Widescreen Version

Brand New Audio Commentary by author Stephen Jones and author/critic Kim Newman

Jones and Rigby return for the final track which compares this film with The Neanderthal Man several times, finds some appreciation of a fairly maligned film like I did, while mentioning oddities such as why it seems to pretend it’s a mystery. Jones wonders how a music man like Gershenson ever became a producer [and not just of this film either], and both point out inconsistencies in the shooting of the ending which seem to betray some reshooting. I’m surprised that they never go into subtext, but then it’s not as if they’re ever in danger of running out of things to say, even getting in a cheeky mention of “a lab in Wuhan”. They’re great company as always.

Production Stills Gallery

Artwork and Ephemera Gallery

Theatrical Trailer

SET SPECIAL FEATURES

Limited Edition O-Card slipcase [2000 copies]

1080p presentations on Blu-ray

Eureka use the same masters that Scream Factory did but probably give them new encodes. Man-Made Monster is understandably the weakest looking of the three due to its age, with some minor print damage and a slightly softer picture, but viewers should still have no real complaints. The Monolith Monsters and Monster On The Campus look very good indeed; the monoliths in the former have a nice sheen to them while the nice use of blacks in the latter is well showcased with hardly any crush. Fans should be very happy.

A Limited Edition collector’s booklet featuring new writing on the films included in this set by film scholar Craig Ian Mann [2000 copies]

While I personally thought that ‘The Monolith Monsters’ worked a tad less well than the others, I had a good time with all three of these films, none of which are classics yet which provide plenty of ‘B’ entertainment and more invention than you might expect. While not loaded with special features, all three audio commentaries are excellent. Recommended!

Be the first to comment