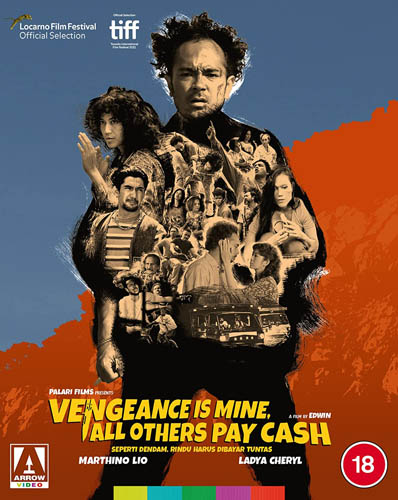

Vengeance Is Mine All Others Pay Cash (2021)

Directed by: Edwin

Written by: Edwin, Eka Kurniawan

Starring: Ladya Cheryl, Marthino Lio, Ratu Felisha, Reza Rahadian

AKA SEPERTI DENDAM, RINDU HARUS DIBAYAR TUNTUS

INDONESIA

RUNNING TIME: 116 mins

Vengeance is Mine All Others Pay Cash is available now on ARROW and released on Blu-ray from 19th September 2022

1989, the Bojongsoang District, Indonesia. Ajo Kawir is a young man who has a very aggressive streak which gets him into fights. He doesn’t have a job, though his biggest issue is his inability to achieve something else – an erection, which may have been caused by a traumatic incident in his past. This especially becomes a problem when he’s asked to kill a man named Mr. Lebe who killed another man and took his wife. Lebe happens to have a female bodyguard named Iteung who fails to stop Ako killing her boss, but who still beats him in a brawl. The two then fall in love and eventually get married, but Ajo is supposed to have killed another at the request of his new boss Uncle Jembul and is delaying doing the deed, while threats from elsewhere are looming. Becoming a more peaceful person may not be the right thing to do right now….

Not knowing anything about Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash, I assumed it was actually an old spaghetti western; several other films are called Vengeance Is Mine, but with the addition of the second part of the title I really did think I was getting an Italian oater. Well, it’s actually a fairly new picture, and one which has won awards at that, though it’s also a throwback in many ways. The aesthetic is that of low budget Indonesian action films of the ’80s, and this is perfectly replicated in look, style and sound, so much so that you’d really think it was from that decade if you didn’t know better. However, it’s not really an action film in itself; while there are a few fight scenes and a hell of a lot of brutal slayings, it’s more than anything else an offbeat love story which, despite its lack of sentimentality, has real sweetness to it. Impotency is hardly a new subject in the movies, and this film isn’t even anywhere near the first to have a man using violence as a substitute for sex which is something he’s unable to have, but it’s handled just about as sensitively as it can be in a film which has most of its characters either going on revenge missions or being victims of them. The screenplay by director Edwin and the writer of the book of the same name upon which it was based on Eka Kurniawan dares to suggest that violence can sometimes be a solution even if a heavily flawed one, and also seems to see its violence and trauma in a wider context, that of Indonesia itself which has suffered repressive regimes and an excessive macho culture. Do Edwin and Kurniawan succeed in properly transmitting all this while putting a lot of quirky, even fantastical elements into what is also a throwback, even a tribute, to a bygone era of filmmaking? Well, they do get lost a bit at times, especially during some passages of the second hour when they’re on the verge of throwing in too much even as things start to lose focus at the same time, and then the film seems to suddenly stop, but there’s usually something to be said for being unpredictable, and there were times when I really had no idea where the story was going to take me.

At first the film seems to be recalling American exploitation cinema of an even earlier time, as if Roger Corman travelled to Indonesia to make one of his youth pictures. We first meet our very very flawed hero Ajo engaging in a sort of duel where two guys on motorbikes have to hurtle towards each other and one has to lean down and pick up a bottle in the road before the other. “Only one who can’t get it up can face death without fear”, says a young boy in a painting to either Ajo or the audience or both, in one of the more awkward odd moments, though it’s not nearly as awkward as it is for Ajo when a prostitute fellating him can’t get him excited, something the lovely woman makes worse by telling him that she feels really degraded by this. We hear about something that happened to him when he was a child though only obliquely, and that his father put chili paste on his penis after it had happened. Ajo is taunted by another guy and starts a fight which he loses when a whole group turns on him. After recovering, he’s given the job of doing in this nasty Mr. Lebe, but is met by Lebe’s bodyguard Iteung. The resulting fight is both funny, exciting and a bit sexual, the highlight perhaps being when, unseen by Ajo, Iteung jumps onto the side of a lorry and onto Ajo’s back. Ajo seems to win and is able to go over to Lebe and slice his ear off, an act not really shown which actually sort of adds to its callous nature, but then collapses before Iteung who’s got back up again, leavign her the real winner of this confrontation. Meanwhile local boss Uncle Jembul asks his top man Iwan Angla to kill a vile gangster named Macan, but Iwan is done with fighting, so Uncle asks Ajo next. Ajo also turns him down because he’s now in love and all he can do is think about Iteung. There’s a beautifully photographed scene where the two go to a still fairground and their surroundings are bathed in a variety of colours, but the idealism of a first date goes when he fingers her but doesn’t want to to return the favour and just gives her a lollipop in one of the cruder bits of symbolism we see. The poor lad, he can’t even get an erection through masturbating when he gets home!

She goes away to study, but keeps sending him messages over the radio along with requested songs, while he drags his heels about killing Macan. Then again Macan is reportedly so tough that, when he had toothache, he refused to go to the dentist and cut off his little finger so the pain caused by that was stronger than the toothache. These people exist in a world of stories and rumours. Despite Ajo being unable to fully prove his love in a physical way, it’s certainly starting to change him, and then he finally confesses his condition to Iteung who tells him that she knew anyway. She wants to marry him, so a wedding is set, despite Iteung’s ex Budi hanging around. He’s going into business with shrimp oil which is supposed to act like viagra, but we never see or hear about Ajo trying it, which is strange, it seems like a natural plot progression – but then Edwin and Kurniawan are often out to surprise us, and more and more as well, so we shouldn’t really consider this to be a flaw I suppose. It seems that Iteung has also been damaged by a childhood incident, while we learn more about what happened in Ajo in the film’s only flashback, though not everything, that’s to be fully revealed later. I did wonder if we could have seen more flashbacks, each one revealing more, but then what we find out towards the end may have been too nasty to depict. Anyway, time passes and little things like prison and pregnancy cause our couple to spend long periods of time without each other. The film also begins to feel its length at this stage, but then we may have needed a more relaxed pace to show Ajo possibly finding some real peace, something which is shown in an ironic light when Iteung surprises us in a rather different fashion. But what’s all this stuff about a third woman who seems to be some kind of ghost?

Indeed there may be some viewers who will reckon that director and writer have lost the plot by now, though said female is yet another link to past abuse, symbolising perhaps even more than the two leads a culture, a country and maybe even a world that’s been largely built on terrible doings. I’d imagine that some reviewers of this film are using the phrase “toxic masculinity”, a phrase I hate for reasons not really within the scope of this review to go into, but the idea at the core of this caused me to think of the recent film Men and its depiction of an endless cycle of men who are abusive in one way or another. Alex Garland did this in a very cack-handed, not to mention unpleasant [seeing as there wasn’t one positive male character in the film] way, but Edwin and Kurniawan chose a much more nuanced approach which really pays off, while it’s always nice and often genuinely uplifting to see a character becoming a better person, something Marthino Lio shows with restraint. Indeed often it’s his expressive eyes which take the lead in drawing our attention and suggesting to us what Ajo is thinking. Ladya Cheryl is perhaps less effective though is undoubtedly better in the fight scenes of which she has more of than anybody else, displaying strong physical prowess and executing moves very well. And there’s one very difficult scene which she plays outstandingly. The sex-starved Iteung, who remains sympathetic, is on the verge of having an affair, and is drawn to pleasuring the lucky guy yet is also disgusted with herself and keeps moving away. The extremities of emotion her character must feel along with basic need are evoked very well by Cheryl, and it’s well staged too in a film which is sexually frank without being very explicit. A grim rape, watched by two little boys, mostly suggests the horror by almost noir-like photography and just sounds.

There are many vicious kills, a few quite ingenious, one or two rather improbable, but then fantasy does explicitly exist in the world of this film, while simple neck breaking remains the most popular method of ending someone’s life. Budgetary reasons no doubt meant that elaborate special effects were out of the question, and most of these moments are shown quickly, from a distance or even mostly offscreen, but that’s all you really need sometimes; the piling up of sudden dispatches in the final act still satisfies our blood lust even though there’s no big fight showdown climax, and it doesn’t actually look like any CGI has been used at all, which is a rarity these days. Martial arts is more used as a weird form of courtship then good guys versus bad guys. – think The Mask Of Zorro or Red Sonja. The Pencat Silat is staged with choreography that’s simpler than we’ve come to expect these days but which seems appropriate considering the ’80s approach. The sequences aren’t the most exciting, but the moves are crisp and clean while the camera prefers to stay back and hold rather then get in there and cut; no rapid cuts or shakycam here. Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash has also clearly been shot on film; if you’ve seen enough films you can tell, celluloid has a certain texture that digital cannot replicate. Akiko Ashizawa’s cinematography manages to replicate the ’80s look and still make it seem new which I know sounds pretty strangr, while the snythesiser – with a few flourishes of guitar – musical score by David Lamenta is perfect. The varied pieces written are all appropriate for the film’s several moods, be they dark, tender or even a bit spiritual, and one of the nicest ones finishes as a mournful song during the end credits.

Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash stumbles sometimes and falls somewhat at the last hurdle which, while it concludes with a rich bit of irony, doesn’t show us something which we really want to see; I know surprises are common in this film but sometimes the audience requires some satisfaction too just like Iteung. But it’s still quite a unique mix of the familiar and the unfamiliar that’s been created here, and one that’s certainly had a great deal of thought put into in terms of what it’s really about and what it’s trying to say, the main thing perhaps being that violence is horrid but sometimes a necessity, because out of it can come calm and balance.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

High Definition (1080p) Blu-ray presentation

Original lossless Indonesian 5.1 and 2.0 stereo audio

Optional English subtitles

Brand new audio Q&A with co-writer/director Edwin

Over an hour of behind-the-scenes footage from the film set, organised into 13 episodes

The World Behind Vengeance – over 80 minutes of interview featurettes with the cast and crew

Video diaries from each day of shooting

An hour of readings from the original source novel, featuring multiple cast and crew members

Deleted scenes

Theatrical trailer

Image gallery

Reversible sleeve feature two choices of artwork

FIRST PRESSING ONLY: Illustrated collector’s booklet featuring new writing on the film by Josh Hurtado

Be the first to comment