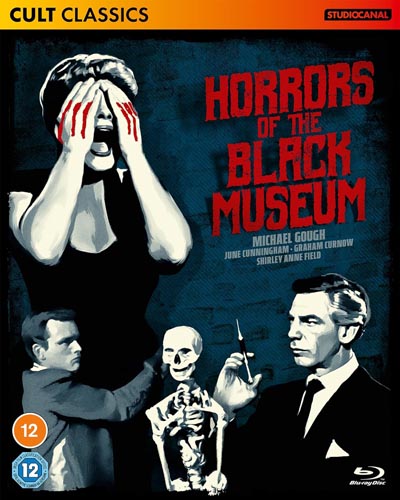

Horrors of the Black Museum (1959)

Directed by: Arthur Crabtree

Written by: Aben Kandel, Herman Cohen

Starring: Graham Curnow, June Cunningham, Michael Gough, Shirley Anne Field

UK/USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY, DVD and DIGITAL: 15th January, from Studiocanal

RUNNING TIME: 83 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

London has just had three sensationalistic murders. Crime writer Edmond Bancroft, who has his own black museum full of bizarre killing devices and dummies of the real-life murderers who used them, condemns the incompetence of the police in not being able to solve the case. But could he be the killer himself, polishing off anyone who displeases him? Though who’s this person with a monstrous visage who sometimes helps him?

The cinema has had body counts in movies since the 1920’s, but what about the slasher movie, or rather the subgenre of film that exists largely to show the audience gruesome deaths, satistying their blood lust in a way that many think is unhealthy? A lot say that slashers began with Halloween or Black Christmas, though that ignores the Italia gialli, which go all the way back to 1964’s Blood And Black Lace, Psycho, and the Vincent Price starrers Theatre Of Blood and The Abominable Dr Phibes [which clearly takes a lot from Horrors Of The Black Museum] and its sequel. And this particular offering, of which you can say that its main reason to exist is to present grisly murders. Yes, there’s a plot, but its constructed in a ramshackle way, doesn’t bother to explain several seemingly important details, and doesn’t even pretend to be a mystery; it’s bleeding [sorry] obvious who not just one but both of the killers are really early on. It’s aim is to just shock the viewer. Of course one’s imagination has to fill in a few gaps because graphic detail is cut away from, but there’s a meanness, a cruelty to this film, and even with BBFC meddling it must have been pretty shocking back in its day, especially seeing as it was in colour. Yes, we’d already had The Curse Of Frankenstein and Dracula from Hammer, but they were set in a somewhat cosy and make believe past; this took place in the here and now which no doubt increased its potency, though to be honest it’s not that great a film in general, largely lacking in style and even suspense. Nonetheless, it’s tacky, lurid fun and a fine showcase for the always entertaining Michael Gough, truly let loose on a horror film for the first time just after he provided such hammy support in Dracula.

Producer Herman Cohen made his name with the duo of B movies I Was A Teenage Werewolf and I Was A Teenage Frankenstein, then moved to England. Cohen read some newspaper articles about Scotland Yard’s Black Museum, arranged to visit it, then wrote a treatment and later collaborated with Aben Kandel on the screenplay. All of the murders were based on real ones – or so he said. Some have disproved his claim that, for example, the film’s opening murder was the exact same method that a stable boy used to kill his rich girlfriend who dumped him. Cohen wanted Vincent Price or Orson Welles in the lead, or so he said – this has also been disputed. He claimed they were too expensive, but by having a British star in addition to a British director and other crew, he could take advantage of the tax breaks provided by the Eady Levy, designed to assist film-making in Britain. The credited producer is Jack Greenwood, but Cohen says this was to ensure the film qualified for the Eady Levy, Greenwood in fact being more of an associate producer. Half the money was provided by the UK’s Anglo-Amalgamated, the other half from American International Pictures. It was the first movie from AIP in colour. Gough claimed that he found Cohen intrusive on set, but still made four further pictures with him despite being called by him “A cut-price Vincent Price”. A fifteen-minute prologue featuring hypnotist Emile Franchele and “HypnoVista” was added for the US release by James H. Nicholson of AIP, who felt the movie needed another gimmick. It made a lot of money both in the UK and the USA, where it was double billed with The Headless Ghost. A stunt for the US release by Ruth Pologe, head of AIP publicity New York, backfired. She reported that Cohen had lost the a certain pair of binoculars used in the film at the airport, unwittingly sparking tabloid front-page headlines and an extensive police search costing a great deal of money. Sadly the BBFC cuts, which were made to every killing, seem to have been in every released print so, unlike some of the Hammer films, a more complete version is unlikely to ever be seen.

Many think that the opening scene is the best one. It certainly grabs you by the throat – or should that be the eyes? After an introductory shot of London and of course a red bus driving by, we see a postman delivering a parcel. A woman opens the door and unwraps it in front of her housemate. Inside is a pair of binoculars. The girl picks them up and goes over go the window and puts them towards her eyes. We cut to the roommate and then hear a horrid scream before cutting back to a shot of the poor victim covering a bloodied face, obviously mouthing the words “my eyes, my eyes” though the BBFC seem to have prevented us from hearing them, then the dropped binoculars on the floor with bloodied spikes protruding from the eye pieces. If the scene was in a film today, we’d probably get a shot of the spikes going in and maybe even the destroyed eyes, but that’s because censorship now allows for so much more than it did in 1959, and having the piercing shown would have actually diluted its effect. In any case, this must have truly shocked 1959 cinemagoers. The roommate is being interviewed by Superintendent Graham and Inspector Lodge when journalist and crime writer Edmond Bancroft enters the room. He wishes to see the binoculars for himself, and Graham remarks on their similarity to binoculars in Scotland Yard’s Black Museum. Bancroft is an expert in crime, but Graham dismisses his idea that the killer could be a woman though without explaining himself, and doesn’t like his sensationalising which whips his reader into a state of panic, while his doctor thinks that this is becoming an unhealthy obsession. Bancroft tells him that after each murder he goes into a state of shock, and Doc thinks that he needs psychiatric treatment and should be hospitalised – which of course is just the half of it.

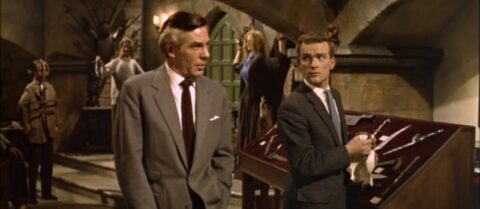

Bancroft returns to his house and enters his secret basement museum with his assistant Rick. The museum exhibits various used weapons and implements of torture. This pretty much tells us, if we hadn’t cottoned on before, that Bancroft is the culprit, and one perhaps wishes that there had been some attempt to keep this a secret for much longer, but then again if that had been the case, we wouldn’t have been able to enjoy as much of Gough off his rocker as we do. There’s a guy who confesses to the crimes before making up other bad things that he did, such as killing a woman who spurned him with a death ray emitting from his eyes, so of course it can’t be him. We don’t learn why Bancroft killed the last victim, or indeed why he killed the other two victims we first hear about. I guess that we’re just supposed to assume that they are more people who pissed him off and paid for it. One murder shows somebody who can’t be him, he looks too different; as somebody says, “old and wrinkled and steeped in evil”. Could this be Bancroft’s assistant Rick, who, we soon find out, is frequently being hypnotised by Bancroft to do his bidding? You’d think that Bancroft would have something on Rick, otherwise why would he continue to work for him even when he wasn’t under his mind control – unless he actually is all the time and the film doesn’t make this clear, which wouldn’t surprise me. The frankly often childlike screenplay doesn’t even explain why Rick undergoes a physical transformation when injected with something, unless you count a speech by Bancroft of which the first half is, “The world thinks Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde were figments of a great writer’s story. But, no, I have clearly demonstrated it is a fact. Man is born with a dual nature. Society tries to suppress evil, but not I”. Cohen probably once thought of doing a I Was A Teenage Jekyll And Hyde then decided to incorporate it here. And is the Bancroft/Rick relationship intended to be read as gay? Bancroft’s hissy fit at finding Rick with his girlfriend [making out in Bancroft’s museum no less!] is perhaps Gough’s crowning moment here.

But then Bancroft is often given to saying crazy stuff, being especially, in a movie where the female characters really are portrayed badly [and only one man is murdered], hateful of women . “One must never place any trust in a woman. It was no secret that Satan was able to tempt Eve before Adam”. “I tell you no woman can hold her tongue. They’re all a vicious unreliable breed”. Yet we’re never told why. He goes mad when he hears a music box play Mendelssohn’s Wedding March, but why? Bancroft is shown to be having a relationship with, it’s suggested, a prostitute named Joan, but she insults him. Is her remark of “without your cane you’d only be half a man” intended to suggest impotency, a fairly common trait of screen madmen back in the day? The way Joan is presented is contradictory, unless our screenwriters Cohen and Kandel were actually being sophisticated [who am I kidding?] and intended us to question our opinion of a woman who initially comes across as a cruel, vain user, the sort of person whom we might just want to see polished off in an inventive fashion. But then she also seems to have been shorn of genuine affection and respect, and goes on to reveal a vulnerability when she goes into a pub and, after dancing reasonably provocatively and also very badly to a jukebox, tells a typically understanding barman that her parents never seemed to have fun so she’s determined to do so. We spend a lot of time with her, even seeing her walk home with her being “escorted” by a pair of policemen, but of course it’s all just build up to perhaps, despite it providing the biggest jump scare in the film [it’s really good], the most absurd of all the killings. In any case, there’s a relish to the deaths that’s rare for the time. Is it reprehensible that many of us horror fans lap this shit up?

Do we think that Bancroft’s claims of investigating the murders are genuine, that he truly doesn’t know that he’s committing them? After all, he says that he blacks out after each murder. I doubt it. He does seem pretty stupid in constantly coming to the police though I guess he just has an enormous ego, and what the hell are those machines in his lair? They serve no purpose except to kill someone who has to stand in just the right place so he can be electrocuted. Again, as all over the picture, things just are, as Cohen and Kandel build makeshift bridges between death scenes; have I yet mentioned the huge ice tongs, or the very surprising stabbing in The Tunnel Of Love where several voices provide seemingly the only [imtended] humour in the film. The climax is a fairly familiar conclusion, echoing the likes of King Kong, White Heat and the two most famous versions of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, but it’s rather well done and contains the only emotive part of Gerard Schumann’s musical score, which otherwise provides a lot of rather atonal force during the highlights but little less. Driven with odd conviction by Fiend Without A Face‘s Arthur Crabtree, whose last film this was, and photographed effectively by cinematographer Desmond Dickinson who uses a muted palette except for the frequent use of red [and not just the blood], Horrors Of The Black Museum‘s idea of script cleverness is the line “why not blame magazines, TV or the cinema” in a talk about murder, but it nonetheless remains rather fascinating and rather fun. But would it have been better with Price in the lead role? A debate on this is playing through my head as I type. First world problems.

Rating:

From a recent scan also used in VCI’s North American release which came out just a few weeks ago, Horrors Of The Black Museum is a little faded in its colours except for of course the frequent use of red which sticks out even more, but grain is even, detail is impressive and blacks exhibit no crush.

SPECIAL FEATURES

Brand New Audio Commentary with Kim Newman and writer/editor Steve Jones

For some reason special features are different each side of the pond, the VCI containing an old commentary track from Cohen himself, plus s newer track and an interview with Shirley Anne Field. Newman’s veteran talk track buddy returns for this track which features both men in top form, Newman’s early comment “It’s as if they tried to make a film that was as offensive as critics thought the Hammer films were” setting the scene for an enlightened, appreciative but also critical [especially about some of the performances] chat about this film. Topics covered include censorship, sexuslity [apparently all of Cohen’s films have the very same gay element], and Cohen who deserves more fame as an auteur producer like William Castle or Val Lewton [it’s even pointed out that all of his films have basically the same plot]. Newman wonders if the Hypnovision prologue was added because American viewers wouldn’t care about a film set in London and is more convinced that the reason was to delay the binoculars horror, while Jones reckons that one scene was largely improvised. Plus we have our attention drawn to a hair on the lens which may be on all prints! Wonderful, perfectly pitched stuff all the way through.

Brand New Interview with novelist and critic Kim Newman [21 mins]

As with Newman’s talk on Studiocanal’s Devil Girl From Mars disc, the man mostly says things which are also in his commentary track. He probably did these featurettes first, and I wonder if it would be best for buyers to watch these before going into the commentary tracks. Of course he does go into a bit more detail as he covers the likes of the treatment of women, Cohen and a writer named Edgar Luffgarten who may have inspired the Bancroft character. He also compares the police scenes in films like this to the non-sex bits in porno movies; I wouldn’t go anywhere near as far as that.

Hypno-Vista Introduction [15 mins]

So hear it is, the introduction for the American cinema version; according to Cohen too many people were genuinely hypnotised so when it first turned up on TV it was removed. Really, Cohen? “Registered psychologist” Emile Franchel sets things off by introducing himself, then talking about and demonstrating the power of suggestion before doing some actual hypnosis and finishing off with bigging up the film as being full of emotion. I can’t say that I was hyonotised. Was anybody?

Original Trailer

B&W Lobby Cards Gallery

An exclusive set of four collector’s art card [Blu-ray only]

This “ahead of its time” shocker nonetheless less interests with its grisly invention, its misanthropy, and its almost admirable lack of interest in logic or coherence. Recommended!

Be the first to comment