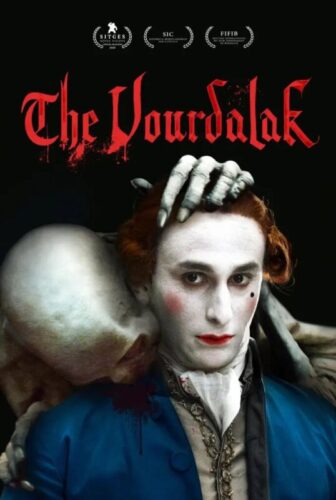

The Vourdalak (2023)

Directed by: Adrien Beau

Written by: Adrien Beau, Aleksei Tolstoy, Hadrien Bouvier

Starring: Ariane Labed, Grégoire Colin, Kacey Mottet Klein, Vassili Schneider

FRANCE

AVAILABLE ON DIGITAL PLATFORMS: 16th September, from BLUE FINCH FILMS

RUNNING TIME: 91 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

It’s the 18th Century and a particularly dark and stormy night. Marquis Jacques Antoine Saturnin d’Urfé, a noble emissary of the King of France, is the last survivor of a group that has been attacked. He’s been robbed of his belongings and horse and is wondering aimlessly through a forlorn forest somewhere in Eastern Europe. He’s taken in by a family headed by Gorcha who disappeared a few days ago looking for revenge on a man named Alibek. He left a letter indicating that if he doesn’t return within six days then he has died fighting. If six days have elapsed and he then returns, the family must not, under any circumstances, allow him back into their home. Jacques Antoine takes a fancy to Gorcha’s daughter Sdenka, but then, during a family lunch, Anja, Gorcha’s daughter in law, spots his lifeless body resting against a tree on the edge of the nearby forest. Jegor, Anja’s husband, recovers it and realises that he’s actually still alive. However it soon becomes very clear that this man is not their father who left a few days ago….

Slavic folklore gives us the vurdulak, though the word actually derives from volkodiak which means – werewolf – which is a little confusing. Horror fans are probably most likely the remember the word from Mario Bava’s classic three portmanteau 1963 chiller Black Sabbath, which includes a story called The Wurdulak, credited to Aleksey Tolstoy in the film’s credits, though his story was actually called ‘The Family Of The Vurdulak’, the novella popularising the idea of the vurdulak being a creature that must consume the blood of its loved ones and convert its whole family. Bava’s version is a neat condensing of the story while delivering the visual beauty and genuine fear that’s made Bava a cult favourite even if he wasn’t much appreciated at the time, though of course in my view he deserves even more appreciation. Well come on – I can never resist mentioning one of my favourite directors and here it’s certainly warranted. There was actually another screen adaptation in 1972 entitled Night Of The Devils, from Italy, this time feature-length, though I haven’t seen that yet, so I can’t compare that version to this one. What I can tell you, though, is that this French effort, judging by the synopsis that I’ve read, seems to be relatively close to the novel while adding some touches of its own, touches which genuinely work. It also transcends what seems to be a very low budget to offer a vampire romp which has plenty of atmosphere, style and bite [sorry] to it. It only goes slightly astray when it tries to be funny, though these bits aren’t frequent and they don’t entirely spoil the downbeat tone, so it’s not a major problem. It has a pleasing old style feel to it; you can imagine this being made somewhere in Europe in the early ’70s.

The opening is as perfect a start to a Gothic chiller as you can imagine. Over a black screen we hear rain and thunder before the middle of the screen reveals the outside of a door to a house and a man’s face looking out from a gap on it. “Open up, for the name of God” cries a voice, “the barbarians kiled my escort, stole my luggage and my horse, I’ve nothing left”. The guy inside isn’t having any of it and replies, “we open the door for no one, fond somewhere else, follow the path heading west, ride without stopping”. We cut to the next day and our protagonist stumling down a hill in the middle of the forest. The Marquis Jacque Antoine is pale-faced, wearing that makeup courtly types often did back then, which makes him ironically look like a vampire while none of the people he meets do so for some time. In a moment which is both beautiful and eerie, he hears the sound of a woman’s voice singing before seeing the lady dancing, feeling free in nature but also with movements which seem a little unnatural. This is Sdenka. Jacque Antoine, who at the moment only wants a horse, then meets her siblings Piotr and Jegor plus Jegor’s wife Anja and their son Vlad. Jegor has spent the past month seeking revenge against the Turks who pillaged the village; he and his group were able to quickly massacre a group of 12. Jegor, much like Jacques Antoine, doesn’t believe in silly folklore and the supernatural, so thinks that all this stuff about the head of the family Gorcha not being let in after six days because he’d have become a vurdulak is nonsense, even though the others are all really worried about the situation. As for Jacques Antoine, he has trouble even finding out what a vurdulak is, but joins Sdenka the next day. She once had a relationship with a traveler who was shot dead [the culprit is relatively guessable]; now nobody will marry her. Jacque Antoine, probably used to seducing courtly ladies, or just fancying a bit of peasant rough, makes an aggressive pass at her, but she tricks him into almost falling off a cliff.

All this is quite leisurely, just as you’d probably expect if this was from five decades ago, but that evening, six days since Gorcha left, he’s spotted lying at the edge of the forest, looking like a corpse. Piotr’s dog will not stop barking at Gorcha, and Jegor compels Piotr to shoot it. Gorcha reveals the severed head of the band of Turks’ leader, whom Jegor failed to kill, which I guess is good. And here is where I need to mention the thing that will probably make or break this film for some. The filmmakers did something brave with their presentation of the vampiric Gorcha. Rather than have him played by an actor, or go for CGI [which might have been too expensive anyway and we al know how horrible cheap CGI can look], the decision was made to use a puppet. Now I love puppets, and found Gorcha’s movements and mannerisms quite unsettling despite certain comic bits like him pretending to die at dinner with his face in a pie, so had no problem with this, but it’s probably fair to say that some viewers may find it distracting. That night, Jacques Antoine has nightmares about Gorcha. The following day, Gorcha is nowhere to be seen and Vlad is unwell. Jegor looks for Gorcha while Sdenka and Piotr, with Jacque Antoine’s help, sharpen a stake and perform a ritual on Vlad, who that night is seen sleepwalking outside. If you’ve seen a fair few similar movies you’ll probably be able to guess how things progress, with some situations that will be familiar to many, though our two screenwriters, director Adrien Beau and screenwriter Hadrien Bouvier, provide some fresh twists on some of them. For example we’ve all seen heroes seduced by the women they like who may now not be what they seem, but here we get a particularly perverse variant.

The final scene adds a stronger tragic aspect to what was in the original story, and it’s nicely set up, even we haven’t had any real sense of a love story. It will also perhaps make some chuckle at what’s going to happen after the credits have rolled. These vurdulak don’t seem to begin as aristocratic types but are clearly s threat to the upper class, in a film which does sometimes look at class; take for example the way that its hero only seems to be able to talk about the environment which he’s come from when he’s trying to woo the heroine. These vampires are quite familiar really, aside from an occasional ability to – it seems – not necessarily take the form of others but get victims to think that they’re someone else. We’re told that holy water [which has to be used by a “holy man”], fire and stakes can kill these creatures whose new found vampirism also gives them a sense of humour. It’s rather touching the way that the young in this movie still respect the old even when not just looking none the worst for wear and doing and saying odd things but being flipping vampires. The horror content is properly set off by a rather frightening scene where Jacques Antoine hears sounds in his room and, after we just about glimpse Gorcha climbing on the ceiling, he sees that Gorcha is actually in his bed, then the screen goes dark and Jacque Antoine struggles to light a match; we’re very afraid of seeing Gorcha again, a character who’s initially quite sympathetic but becomes a particularly terrifying and also intelligent vampire even when not having much screen time; but neither did Christopher Lee in his Draculas. There’s an appropriate amount of blood, perhaps shown most strongly in the scene where Vlad is graphically bitten. We don’t tend to see kids being bitten in detail; think of Vampire Circus, where two young boys are certainly bitten but the camera avoids showing the details of the act. Here, it’s dwelt upon, which perhaps makes us thankful for this film not bringing in any sexual element to this stuff except for one particular scene.

The relatively limited practical effects more than do their job, but subtlety is also often employed in a film which seems to take in influences from Nosferatu to the cheapie offerings of Jean Rollin, with their cast members playing around in real decayed old castles. The one here is marvelously shot, especially the interiors which often seem to be filmed only with natural light; far less effective are some overly blue-tinged, day for night sequences, but then Beau is looking to the past as much as or more than the present in his film. Far more visually appealing is David Chizallet’s gorgeous outdoor cinematography of the fields and the forest. A lot of attention seems to have been paid to costume design too, courtesy of Anne Blanchard; just look at how well Sdenka’s dress mixes with the ground of the forest. And Beau and Chirallet adopt a very classical, methodical filming style which seems at odds with much of what we see today but which certainly seems to suit this particular endeavour. A very slow pull out from the face of Sdenka to gradually reveal her among four others with a dead body before them is extremely poignant. There seems to be an emphasis on Jacques Antoine seeing, watching, observing, which reaches its peak with a scene where one of the most dramatic ‘biting’ moments of the story is seen from a great distance, from the point of view of Jacques Antoine as he looks out of a window, the camera never cutting closer. Rather than hampering the emotional effect, this approach makes it even more devastating, with our hero totally unable to stop a cycle which has probably happened in many other local families. Beau and Bouvier seem to be giving us a message throughout which is warning us of the danger of letting love make us blind to danger.

Kacey Mottet Klein does very well in an unconventional lead role; other performances tend to veer on the theatrical side but this seems to fit in with the film’s slightly campy approach. The character of the effeminate Piotr is the only major element to more modern tastes, unless you count the perhaps overly restrained music score from Martin Le Nouvel and Maïa Xifaras. Every now and again the vampire movie, which never really dies but sometimes does seem to lie dormant for a bit, receives a major dose of lifeblood which causes it to revive. Beau’s rather nostalgic but also fresh-seeming offering seems somewhat vital right now.

Be the first to comment