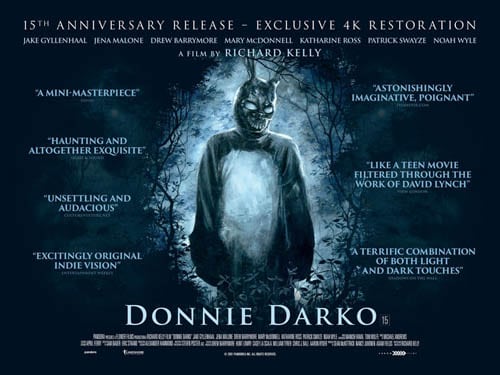

How time flies! It’s amazing to think Donnie Darko is now 15 years old. That means if the film were a person they’d be old enough to undergo the usual growing pains of their voice breaking, hairs showing up in odd places and a giant man in a bunny suit telling them when the world’s going to end. And it hasn’t dated a day. To celebrate the amazing restoration (reviewed here) HCF sat down at a round table discussion to speak with the very talented writer/ director Richard Kelly. We talked about music, wind and improv.

How was it revisiting this film 15 years later?

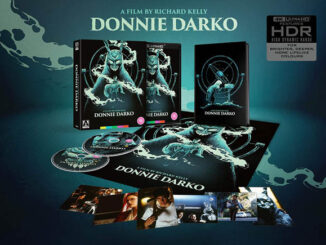

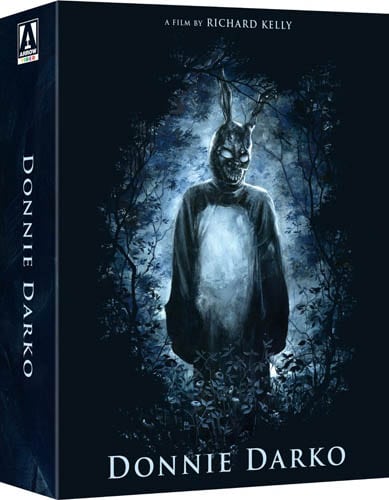

Great. Arrow Films contacted me because they wanted to do a 4K restoration and that was music to my ears. Because the film has never been properly maintained and I was never happy with the transfer or the bluray and anything like that. It never looked right and it hadn’t been preserved properly or transferred. And so they gave us this great resource to go back and find the original negatives then use all today’s technology to present the film in a whole new light – like nobody’s ever seen. We did visual enhancements in places where things hadn’t been done properly. So it’s been great.

With a decade and a half of hindsight how do you feel about the theatrical cut?

I don’t favour one cut over the other so during the restoration we did both cuts so they’d both be available. And I was actually able to do more to the director’s cut because there was some stuff we never managed to do properly and we improved effects in these places. But I think I wanted there to be the 2 versions because I wrote the time travel book – it’s there. I’m not the kind of person who puts something like that in a movie without figuring out what’s inside it. I had to figure it out. And it wasn’t necessarily appropriate for the theatrical cut because it was a running time issue. The director’s cut is a lot more novelistic – it’s sprawling and it’s a lot more science fiction. Though it’s all information that’s there. I think both cuts have their virtues, and I’m not fully satisfied with either of them, but they are what they are. I was glad they got to be remastered though – they look great now! Plus a lot of people won’t ever have gotten to see it on the big screen.

When it originally came out it took a while to find its audience. But when it did do you think it caught something in the zeitgeist?

It really caught on first here, in the UK, for whatever reason. I mean it caught on in the US, but not as quickly. When I came over in 2002 and I was blown away by the response – it was really life affirming. I was just overwhelmed: it gave me a second wind. I don’t know why it was here, maybe something to do with the music being all UK pop songs. It’s an American story but there’s something universal about being a teenager and confronting the big metaphysical ideas in the film. But maybe it was something about the pop music.

How important were those musical sequences to you?

I love incorporating music into my films and it’s always be design. It’s planned ahead or written into the script. And those are the moments that, to me, are the most cinematic. I always want to protect the lyricism. It’s sometimes a challenge to do – like that Tears for Fears sequence is at least two minutes long. Nobody’s speaking dialogue and it’s just people moving through space and connecting – there’s a lot of story and a lot of narrative, but when you’re dealing with a studio and people want the running time shorter then they’re looking at that as two minutes of superfluous, self-indulgent lyricism. And I’m like ‘that’s why I’m doing this!’ So a lot of the time these bits make the film unmanageable and it becomes a real fight to protect this stuff because again, nobody’s talking.

When did you know that school scene was particularly precious?

From the very beginning – it was written in the script that when Jake’s feet hit the ground then that piano note sounds and Tears for Fears start. I saw it and it had to be this way. Like in Southland Tales, when Justin Timberlake lip syncs to The Killers, it was the same thing. He’s got all these dancers and a Budweiser, and that’s how I saw it. Then you got to convince the producers to let you take a day out and film it. They’re like ‘you don’t have the rights to the song – you’re fucking insane. The song might cost $200,000 and we don’t have that’. It’s crazy, but you got to pick your battles. Those are the ones I picked.

Something that’s changed in the last 15 years is the way we think of celebrities. As such, what do you think of Patrick Swayze’s character in light of recent scandals?

When we made it in 2000 there wasn’t any big high profile sex scandals involving celebrities, so I think we were just satirising this self-help guy. He’s shown up in town and he’s like a snake oil salesman. He’s clearly full of shit, so we asked what could be the worst possible secret – the most sinister backing story for this character. So we thought ‘what if he’s a child pornographer? Let’s go with that’. Then he became one of the multiple villains in the movie. You got different degrees of antagonism – the bullies then Frank. Though he’s more metaphysical. There’s a lot of archetypes in there.

A less known actor at the time was Jake Gyllenhaal. Was he immediately what you were looking for in a Donnie?

You know that a film’s connecting if you can’t imagine anyone else in the role. It had to be Jake – had to be! And he just worked really hard. We both spent a lot of time with the script going through every scene. He’d ask me to make adjustments to dialogue. It was a really delicate emotional balancing act trying to modulate the arc – where he is today and yesterday. We shot it all out of sequence – you have to on an independent movie. So we mapped out the timeline and where he was emotionally every day of shooting and where he’d be on the calendar for each of the 28 days.

Did the improvisation greatly change the script?

I always do a bit of improv. Like Southland Tales, we did a tonne – we had half the cast of Saturday Night Live so come on: we’re doing improv! So I always leave room for a bit of it. It’s the best thing when you’re onset and someone has a great idea that’s not yours. You got to own it. You don’t steal it. You thank them for the idea because it’s a collaboration. So if an actor says ‘hey, why don’t we try this’ and its working and it’s funny, touching, frightening or emotional then that’s a blessing. So I’m always down for improv. If my dialogue isn’t working or I’ve over or under written something then it’s open to change. But the foundation of the script has to be sound, and with this script we had a very solid foundation to work off.

Looking back would you have liked the success to become later. Did it leave you with a feeling of having to make a ‘difficult second record’?

Hindsight’s all 20:20 – the order was meant to be the order. Remember it was a disaster first – it was a flop at Sundance then the US cinemas – so it took time. All the movies take time and I’ve learnt you can’t really control the wind. When a movie gets released the wind is either blowing at your front or your back. You can’t control it. So I just try to follow my instincts. On the next film we’ve been careful to make sure all the elements are in place so I hope the wind is at our back.

When you first had the wind against you was it difficult?

Oh yeah, it was really sad. We thought the movie was going to be taken away from me, be cut to 85 minutes and all the music would be removed and it’d be dumped straight to home video. That was very likely to be happen at one point. But we survived it and figured it out. But yeah, there was some dark times but that’s Hollywood. Got to survive it and figure it out.

In all your films you portray a very flawed humanity. Is there something that attracts you to this theme?

The first 3 films I made are definitely dealing in some big apocalyptic themes – not only them but there’s definitely a disturbing confrontation with a lot of dark stuff. I mean all my main characters die horrible deaths. But for these three films they almost feel parts of a bigger story – they’re all connected in ways people probably don’t realise yet. But I think they’re more compelling stories. Though I don’t only want to make films that are dark, so to speak, I’d love to make films that are more optimistic and have a happy ending. I am capable of doing that. I’m also capable of not killing everyone and blowing up the world. But all three of these films felt like they were part of one bigger story and they’re all connected in some ways. I’m not wanting to continue being Apocalypse Boy.

In that case, do you see yourself moving to a new genre?

I’m working on a lot of new stuff and working on new directions – I don’t ever want to be repeating myself and I don’t ever want to become complacent or surrender to the marketplace or be cynical. I just want to keep moving forward and exploring new kinds of stories and new ideas. So you’ll be seeing me move in a lot of new directions.

DONNIE DARKO 15th Anniversary 4K Restoration will screen at the BFI from 17th December and in cinemas nationwide from 23rd December. BFI Tickets are on sale now

Be the first to comment