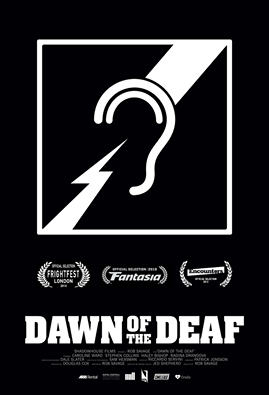

Among the last year’s coolest movies was the 12 minute short Dawn of the Deaf: a low budget zombie flick that showed at over 100 festivals, winning loads of rewards. It’s a neat twist on the zombie subgenre, with a pulse turning all but the hard of hearing into flesh eaters. The result is gory, dramatic and surprisingly poignant. To celebrate the film going public on Vimeo (you can watch it here), where it was launched as a staff pick, Horror Cult Films got in touch with director Rob Savage. Here we discuss his upcoming feature-length version, the festival circuit, discrimination and how easy it is to get undead extras.

What about the concept most excited you?

I’m an unapologetically huge zombie fan, and it’s always been on my film bucket list to contribute something to the genre. However, it’s such an over-stuffed genre that I knew it would take a really unique and unusual idea for me to get me excited. I was getting drinks with horror-buff, writer, record producer and all-round-busiest-man-I-know Jed Shepherd, and he pitched me the idea of a Deaf-led zombie movie where the infection is spread through sound, and I knew right away that it was the idea I’d been waiting for. Horror is so much about perspective, about subjectivity and objectivity. As a director, you are always making decisions about where to place an audience: do you root them in the character’s perspective, allowing surprises to hit the audience at the same time as the character, or can you wring more tension from the Hitchcockian method of allowing the audience to see the danger before the character does? Having Deaf lead characters pushes this to an incredible extreme, letting all sound drop out so that the audience is trapped in the character’s perspective, no sound alerting them to danger, or allowing audiences to see (and hear) things that the character cannot.

What have been your favourite zombie movies to date?

I’m a huge, huge Romero fan (obviously) – I love Night (both versions), Dawn (both versions), Day (Romero’s original) and Land. But the most brilliant Zombie movie of the last tens years is Bruce McDonald’s Pontypool, which is one the most original and audacious take on the genre I’ve seen in a long time.

As an independent short, with a big scale, was there much difficulty with the budget?

We made the film for only £7000 but from the beginning, we aimed to make the final product look as though it cost 10x that amount. The script was written around things that I knew I had access to – the tunnel belongs to an organisation I do some teaching for, and so we got access for free; we shot part of the film on the iPhone so that we could build in a greater sense of scale for almost no money.

In terms of script and sound design, what obstacles and opportunities did a script with deaf protagonists present you with?

The sound mix is one of the elements of the film that I am most proud of, and is entirely down to our fantastic Sound Designer/Mixer Callum Sample. We spent many months experimenting with just how far we wanted to push the sound design, making sure not to over-stylise and risk disrupting the flow of the film. Obviously we knew that at some point the sound would have to drop out (though never to complete silence) and we’d enter the headspace of one the Deaf characters, a moment we wanted to have a huge impact. Our first mix used this trick a lot, and while it was cool, it was having the opposite effect than what we wanted: it was alienating, never allowing us to fully settle into a scene. Ultimately, by watching the film, again and again, it became clear that there were a few choice moments where the visuals were suitably stylised to allow us to be bold with the sound design, particularly during our big show-off Steadicam shot that sets the horror in action. For the most part, we decided that the first half of the film was about normalising the Deaf characters in the eyes of the hearing audience, and so we adopted a more conventional approach to the sound design.

Given the constraints of independent movies, were you able to cast actors who were deaf in the leads?

Some of the actors are hearing and some of them are deaf. That’s the thing with short films; you can’t always make the film in the ideal conditions. Obviously there’s no substitute to using Deaf actors in Deaf roles and that’s what we’re committed to doing with the feature, but we had a funding opportunity to use a specific group of hearing actors so we took the fund as a means of making the short, which is a proof-of-concept for a feature film version. For this, we are committed to using Deaf actors in Deaf roles. Which isn’t in any way to disparage the hearing actors in the short, because they put in three months of prep and they really did give incredible performances.

Did people jump at the opportunity to plays zombies for you?

It’s so, so easy to convince people to be zombies! We had almost 500 extras in the film, and most of them were my Facebook friends doing me a favour. We hired an amazing “Zombie Wrangler” who goes by the name “The Zomboss” and he trained our extras to be shambling undead.

The scenes with bodies around London looked great.

We made the film for peanuts but always knew that in order to convince the audience of the magnitude of destruction, we couldn’t hold back. After wrapping the main shoot, we arranged a series of early morning trips to various locations in London with an army of committed extras and a bucket of blood. As the city was waking up, they were lying across the streets of London with corn syrup running from their ears.

Were you worried about the relatively long time spent world-building before the horror starts?

This is something a lot of people comment on – it never really occurred to me as I was writing the film, it just seemed a natural way into the story and the characters. It’s the kind of approach that would be stamped out in the development phase if this were a feature film or a short with any significant funding. We’d be told that unless zombies appear from minute two, people are going to zone out. And that was one of the main reasons that I wanted to make the short – as a proof of concept not only for the idea but for my own brand of genre filmmaking. Many filmmakers are reticent to call their films “Horror Movies”, instead of labelling them as “Psychological Thrillers” or similar, and this speaks to the way in which the genre is viewed by many – as trashy or low-brow, something beneath a real filmmaker. Frankly, I think this is bullshit. Some of the most intelligent, innovative films I’ve ever seen have been horror films, and with Dawn of the Deaf, I wanted to make a film that treats its characters with the same depth and curiosity as a drama so that when the danger finally hits, the audience is fully immersed and emotionally involved.

How’s it been touring this piece around the festival circuit and watching it with a crowd?

Amazing. We’ve played at over 100 festivals, both mainstream and genre, and it’s always a thrill to sit in and feel the tension build in the audience as the horror starts to creep in. Sundance, in particular, was amazing – I’ve been submitting films there since I was 15 years old, so to finally be invited was genuinely a dream come true.

Numerous critics have praised you for packing so much into a short movie – including multiple scenarios and characters – did it seem too ambitious at first?

I tend to be very naïve about these things. My first movie was a 90-minute feature film that I made for nothing at the age of 17 – I walked into that experience with blind confidence and somehow managed to pull it together, and it was a similar situation here: we knew that the film was ambitious on the money, but the sheer scale of it didn’t really hit until we were in the middle of it, and there was no way out. That’s how I like to work – jump in the deep end and then learn how to swim.

Has the terrific response made you more excited or nervous about expanding it to a feature?

More than anything, I feel validated. So many people have told us that there is no audience for a film with Deaf characters in the lead roles, and the success of the short has proven them wrong. From the first conversation with Jed, the end goal has been to make Dawn of the Deaf as a feature film. While the short is reasonably self-contained, we made it as a means of convincing investors and audiences alike that the concept had potential as a mainstream horror film that would engage with both hearing and Deaf audiences. For us, the main aim is to make a compelling, unique and pant-wettingly scary horror film, but we also firmly believe that the film could be a powerful means of bringing Deaf talent to the screen. Horror isn’t driven by star power, but can still draw a large mainstream audience if it delivers the goods, so we are hoping that the feature film – which will be made with an entirely Deaf cast – will be a step towards greater diversity on screen.

For the full-length version do you intend to revisit some of the characters introduced here?

the feature isn’t exactly a continuation of the short, although a few of the characters and scenarios will reappear in one way or another. It’s going to be a lean, visceral genre film that allows audiences to gain insight into an underrepresented group of people – all while being scared shitless…

Typically zombies movies are rife with social comment – in the large piece do you intend for the hoard to stand in for something in particular?

Not so much – all I really want to do is make a rollercoaster zombie horror that happens to feature “disabled” lead actors. I want it to be a terrifying date-night movie that both Deaf and hearing audiences can both enjoy. If anything, I hope the film will cast some light on the Deaf experience for those who haven’t had any interaction with the culture. The Deaf make up around 5% of the world, and so when 95% of humanity becomes zombified, it really brings that divide into focus.

You can also like Dawn of the Deaf on Facebook or follow on Twitter.

Be the first to comment