Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror (2019)

Directed by: Xavier Burgin

Written by: Ashlee Blackwell, Danielle Burrows, Robin R. Means Coleman

Starring: Ashlee Blackwell, Ernest Dickerson, Jordan Peele, Keith David, Ken Foree, Meosha Bean, Robin R. Means Coleman, Rusty Cundieff, Tananarive Due

HORROR NOIRE: A HISTORY OF BLACK HORROR

Written by Xavier Burgin

‘We’ve always loved horror’ says UCLA professor Tananarive Due towards the start of Horror Noire. ‘It’s just that horror hasn’t always loved us’. It’s interesting that a genre often lauded for championing outsiders, and marginalised communities, seems to have such a blind spot for race. After all, she says, black history is full of horror. Xavier Burgin’s documentary argues discrepancy is because white voices have shaped the genre. Hence, people of colour are, more often than not, left out of the narrative. Where they are included, it is generally as sidekicks, criminals, buffoons or sexual aggressors – not the sorts of characters young people want to grow up to be.

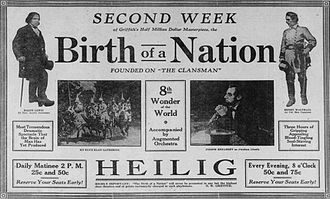

Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror charts the history of black people in America’s involvement with the genre. Among other things its contrasts onscreen depictions with real-world events and movements. The link between the two is underlined, with the first film covered being Klan superhero movie The Birth of a Nation – lauded by Woodrow Wilson, then President. During it, the KKK ride to the rescue of a white woman who is being pursued by a horny black man (actually a white actor in blackface), and then lynch him. From there, the dominant representations of black characters in US cinema seemed to be unflattering, and the doc does an excellent job of digging up old footage to show the different caricatures: randy, dim or beastly. There are of course exceptions – mostly pioneering black directors such as Oscar Micheaux who showed the affluent black middle class, including a lawyer and a doctor at a wedding. Rather than being othered, these were characters not dissimilar to white protagonists.

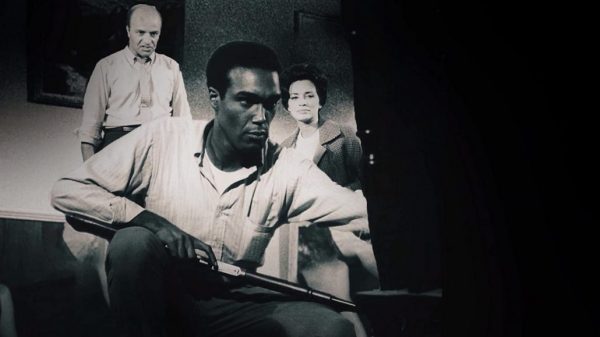

However, these portrayals became increasingly rare in the 50s and 60s, when genre cinema moved towards science gone wrong narratives – where the monster stood in for anyone that was not white. It is through this lens that I was better able to understand the importance of Night of the Living Dead. Though nowadays it’s weird to see Ben punch a woman in the face, back then it would have been weird to see Duane Jones in the role. A role which, for the movies, was a different sort of black identity: someone the interview subjects see as a ‘destroyer’ instead of a victim. He was a handsome, heroic lead in charge of his own fate. It a tragic irony that even in a world where the dead walk the earth, he isn’t taken down by the many white zombies he kills. Instead, it is at the hands of law enforcement, with a bullet. A sad and pertinent ending, almost adopted by Jordan Peele before the success of Black Lives Matter convinced him do otherwise.

The section on blacksploitation is perhaps the movie at its most rewarding. One of the best things about Horror Noire is it underlines that there is no monolithic view. Instead, the commentary highlights a fascinating tension between these films being there to get bums on seats and using the medium to advance black representations. Nowhere is this better shown than the frankly nuts sounding Abby: a celebration of black womanhood via the unfortunate metaphor of possession by sex demons. Where modern viewers, and many at the time, see the focus on big collars, hats and pimp sticks as deeply regressive, one of Burgin’s through lines is the importance of visibility. Often, reactionaries conflate audiences getting to see people who look like them onscreen with ‘political correctness’. To me, this dismissive reaction ignores that people tend not to political messaging in films to the extent that they support the establishment. Thus Captain Marvel being a woman is no more about pushing an agenda than Captain America not being one.

I go with superheroes because Blacksploitation isn’t a genre of movies I know much about. For instance, it was news to me that Blacula is a classic. From the name, I figured it was a slightly campy spoof, rather than a subversive look at vampire lore which shows a centuries-old black character fighting the transatlantic slave trade. As such, I can’t come down on either side of the debate concerning how helpful these films were for opening the door slowly. But I can say I found it enlightening to see others have the conversation. Likewise, some of the talking heads later say Candyman is problematic, relaying the old tropes about a black male obsessed with a white woman – something that never even occurred to be. Whereas others see it rooting its threat in American racial history as being empowering. On that point, the documentary gets more optimistic as it goes on. It’s a myth that during the slasher era, the black character would always get offed first. However, they would almost always get killed – that’s for sure. Or, as is pointe out here, be used as a prop to show how badass the baddy is. Nonetheless, Horror Noire shows how the nineties, though not a strong period for horror in general, were surprisingly positive for black roles.

Maybe the most moving part of the film is seeing Rachel True discuss the response to her performance as Rochelle in The Craft. Originally written as a character with an eating disorder, after she was cast the writers added a racial element to her story. No, she didn’t get to read for the lead, and it’s sad hearing her talk about the numerous times she’s had to practice new ways to say ‘are you ok?’ But when she talks about how young black girls have responded to her, it is clear she sees progress. This section gave me a new appreciation for The Girl With All The Gifts, which True says she wishes had come around when she was starting. John Boyega’s star-making moment at the end of Attack the Block also takes on a new meaning. Heck, even Alien vs Predator becomes profound. We end at Jordan Peele’s Get Out: the first film that was written by a black filmmaker to win the Oscar for best original screenplay and one of few horrors to be legitimised in that way. It’s a film I have always rated, even if I possibly prefer Us, and it is made even better with a brief dissection of some of its symbolism. Peele provides some thoughts on what he was going for plus its response. I’ve always admired how unpretentious he is, even when talking about scholarly topics, and here he’s no exception. A brilliant filmmaker, no doubt, but he’s still a fan first.

On this point, something that separates Horror Noire from a lot of other docs is its intimate style. Much of it is interviews, which you would probably expect. However, many of the creatives are also paired up, with Ernest Dickerson (director of Demon Knight) beside Rusty Cundieff (director of Tales From the Hood), or Ken Foree (Dawn of the Dead) with Keith David (The Thing). It’s a smart choice makes for a laidback, sometimes even fun atmosphere that allows us to get to know the artists. When starting this film, my points of reference were limited meaning that, like the best documentaries, I got from it. Including a long list of flicks to see – starting with Blacula. More importantly, it’s no coincidence that I viewed this at a time when large-scale protests are encouraging people to consider structural forms of racism that influence how society is organised. By amplifying the voices of black filmmakers, Horror Noire is an entertaining, and invaluable, tool for educating oneself about the need for them.

Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror is exclusive to Shudder.

Be the first to comment