A Snake of June (2002)

Directed by: Shinya Tsukamoto

Written by: Shinya Tsukamoto

Starring: Asuka Kurosawa, Shinya Tsukamoto, Yuji Kotari

Available now from Third Window Films and on VOD

One day I hope to enjoy life with even a small amount of the insane energy found in the 16mm films of Shinya Tsukamoto. In some ways this all culminates here in this claustrophobic tale of pouring rain and pouring emotions. There’s a whole lot of rain and a whole lot of questions about what it means to be alive, but make no mistake this is no soul searching Kurosawa picture. Instead the focus is on shedding inhibitions and breaking out of routines in an entirely different way. Whether the central characters want to or not. It’s a very blue movie in more ways than one, a story filled with struggles for control and for privacy. There may have been some elements of sexual transformation in his prior films but it’s all been leading up to this.

Suicide hotline councillor Asuka (Rinko Tatsumi) has a fairly mundane existence. In her day job she puts on a professional voice and helps those in need, and at home she puts up with a sterile and detached marriage. In both of these situations it feels like she’s acting out a role, even if one is more admirable than the other. How she became involved with her husband Shigehiko (Yuji Kotari) isn’t clear since he sleeps alone and only seems to care about cleaning the bathroom. But this a movie that feels anything but clean despite the number of bathroom scenes. The real Asuka is hidden away in one of these rooms where she can be sensual and let out her pent up frustration. But she hasn’t considered that her privacy might be ruined by voyeuristic intruders.

Of course I’m not talking about the viewers of the movie or the film makers, although this meta aspect is up for consideration. The problems begin when photographer Iguchi (Shinya Tsukamoto) is given a new perspective on life after receiving her advice through the phone service. Now he feels that he should return the favour and help Asuka become who she wants to be; the outgoing lady he spied wearing short skirts and looking at catalogues for sex toys. To achieve this he gives her a thorough talking to over the phone and sets her straight on her own life. Just kidding, he blackmails her with photos of her private time and makes her go into the city where she can do it all in public. It’s a bizarre and oppressive setup, and things only get weirder from here.

This idea of role reversal permeates the whole story as Iguchi soon becomes a more lonely and pathetic while Asuka starts to transform into a dominant and decisive figure. There’s still an element of the self destructive to Tsukamoto’s characters, but there is also more catharsis than ever before. Even if it’s still a story being told through the lens of the repressed and the perverse. Iguchi’s problems become more prominent as Asuka begins to use his own tactics to her advantage. After her public embarrassment she turns the tables not on him but on her husband, who may not be the toilet scrubbing bore she knows. When she has nothing left to fear the narrative becomes more outlandish and fantasy like, particularly when Shigehiko becomes entangled in a strange kidnap peep-show of some kind.

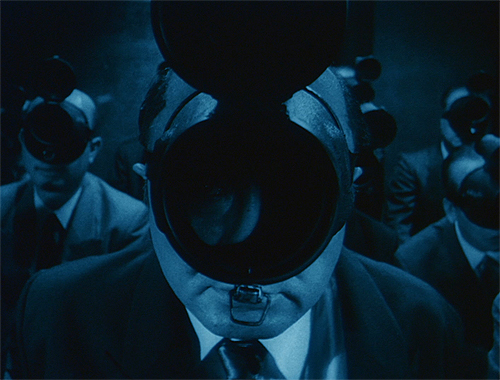

This dreamy atmosphere is enhanced by the film’s use of monochromatic photography and its full screen format. So are the themes of the story. Extreme close-ups and extreme angles give the whole thing a sense of looking through a tiny window even before things go off the rails. The industrial filth of Tetsuo makes a return in several sequences as reality bends and cracks. And then there’s the endless rain; occasionally cleansing but always cold and harsh. Even the blue tint feels like a facade, mirroring the layers each character puts around their grey lives. They’re all stuck in this tiny world as the water floods in. The audience is sure to feel trapped with them as things escalate. At times it may seem that it’s simply a case of wish fulfilment for Iguchi or Asuka, but in some of the more surreal moments it’s hard to decipher who wants what.

The nebulous character arcs stop the film from being compared to a rape revenge thriller, or from being as simplistic as the Saw movies that arrived a couple of years later. Is this kind of perverse exhibitionism really what living is all about, or is it just another veneer? Asuka certainly doesn’t seem sure of herself when she bumps into one of her other clients in the street. Perhaps there’s a reason people can’t be themselves one-hundred percent of the time, choosing to put on different masks for different social reasons. Then again perhaps letting it all out every so often is necessary in a world that demands personas and double standards. Even if the methods employed to shake people out of apathy are reprehensible. It’s telling that the story is filled with sadness instead of rage. There’s no sign of the June wet season ever ending.

Overall this is a story full of these kind of lingering questions. There’s a richness to the look of the film and the characters which leaves a mark. It’s something that is missing in Tsukamoto’s less dynamic films such as Gemini and Vital. Maybe the film format choice is indicative of the projects he was most enthusiastic about. It certainly feels more personal, and the results are certainly more timeless. Perhaps he just knew which stories would always be categorised as cult viewing. Not everyone will watch a film shot entirely with a blue grading. Or a film about stalkers, vibrators, and drowning. But if you’ve made it this far into the world of extreme cinema this is also a well crafted drama. It’s seedy but never crass, claustrophobic but never smothering. Perhaps the director will return to these kind of grainy hand-made nightmares in the future.

Be sure to check out the other reviews in this series

Be the first to comment