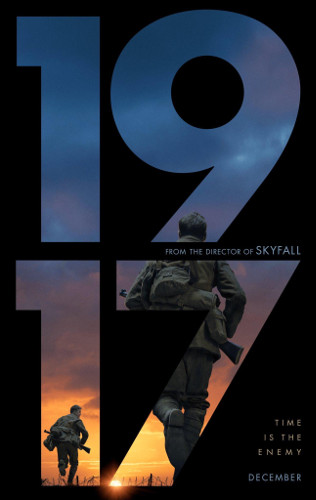

1917 (2020)

Directed by: Sam Mendes

Written by: Krysty Wilson-Cairns, Sam Mendes

Starring: Colin Firth, Daniel Mays, Dean-Charles Chapman, George MacKay

USA

IN CINEMAS NOW

RUNNING TIME: 119 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

During the First World War in April 1917, the Germans have pulled back from a sector of the Western Front in northern France, but aerial intelligence has learned that the Germans are not in headlong retreat but have made a tactical withdrawal to their new Hindenburg Line, where they have prepared to overwhelm attacking British with their artillery. With telephone lines cut, two British soldiers, Blake and Schofield, are ordered to hand-deliver a message to the 2nd Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, calling off their planned attack, which might cost the lives of 1,600 men, Blake’s brother Joseph being among them….

Spectre opened strikingly with a lengthy tracking shot that began high above the heads of a Mexico City Day of the Dead parade before zeroing in on a skull-masked 007, then following him as he weaved in and out of the legions of ghoulishly made-up revelers, up stairs, down hallways and out onto a ledge where Bond coolly walked across precarious rooftops. It’s highly doubtful that it was a single take, but it sure looked like one, director Sam Mendes unashamedly showing off as well as, perhaps, reacting to all those makers of action scenes who think that rapid pace editing is the way to go. And now Mendes has followed that up with an entire film constructed around the illusion of a continuous take, with even one of the advertisements for it emphasising this aspect far more than anything else, quite an unusual thing in this day and age. In it, Mendes said how he was employing this device so that viewers could experience things from the point of view of the two main characters, and therefor get an impression of what the World War 1 experience was like. Of course it’s not totally from the point of view of the two main characters – if that were the case, then we wouldn’t see them nearly as much and the camera wouldn’t sometimes do things like track past a wall to rejoin them at the end, or give us wide high angle shots. But, watching the film, it is certainly very much as if we are another person accompanying them. Of course there are some cuts, there would have to be, and, while one moment when a character is knocked out and the screen goes black for a few seconds seems like it was deliberately intended to be obvious, a couple of others were noticed by yours truly, one with somewhat iffy CGI. But for the most part it’s all very smooth, even though it must have been a difficult achievement to pull off, and there were a few times where I almost forgot about it. The lack of shakycam and whip pans also helped immensely.

But is 1917 any good if you put to one side the way it’s shot? I wasn’t initially going to review it so did browse a few early reviews and, despite its Academy Award nominations, they were more mixed than I expected, though none of them were terrible. I’m going to agree with those who considered it to be decent, but a tad underwhelming and not one to put up there with the great war films. It has some very memorable moments, two or three of them very affecting, and somehow transmits to the viewer the hell of war without showing lots of explicit violence and graphic gore. In fact I wonder if Mendes was originally aiming for a ‘PG-13’ certificate in the USA as only one scene – a track through a medical tent with some dimly lit but still grim carnage – I would say warranted the ‘R’ rating. But it never feels as if punches are being pulled. However, there’s a hollowness to it for much of the time, at times it doesn’t quite seem to be sure what type of war film it’s trying to be, and the first half hour or so is so incredibly tense [and I mean tense – it literally gave me heart palpitations on a few occasions] that what follows just can’t help but fall short despite a few bursts here and there. While there is plenty to praise, I do wonder if so much focus was spent on the complicated technical aspects that not quite enough effort was put in elsewhere to make it a fresh take on the war movie.

We open with a moment of calm as we join Blake and Schofield having some rest. I could have done with a scene or two introducing them more as people, though I guess the intention was to present a “just another day in the lives of…” feel. Blake is presented as the chirpier of the two who likes to tell funny stories, while Schofield later tells of how he exchanged his medal for a bottle of wine, a moment that hints at a film which will have things to say about war and gallantry and rewards, though it disappointingly ends up saying very little except that war is hell. Any way, the two are promptly sent off on their mission which is unusually to prevent an attack, and we’re certainly continually aware that the lives of loads of people are at stake. As Blake and Schofield begin their journey, one really is on the edge of one’s seat. As we move with them through No Man’s Land, the intensity is incredible as we think that a German soldier could jump out or fire some bullets at them any moment, that a trip wire or mine could suddenly be stepped on and blow them to bits. It probably sounds like I’m saying this because HCF is first and foremost a horror site, but we really aren’t far away from the horror movie here [as indeed we weren’t with Dunkirk either, which cleverly exploited primal fears]. When planes suddenly appear and fly over, it has almost the same effect as a moderate jump scare, even though the planes end up being friendly. When a dogfight is witnessed from a distance and a shot down German plane appears to crash over the horizon but then suddenly reappears to threaten our two men, it’s a genuine, full-on moment of shock and fear. We’re continually anxious as to what might be round any corner, even as to what might be on the ground. I’d love to see Mendes try his hand in the genre as he truly proves himself able to create considerable anxiety and fear in 1917.

The two reach the original German trenches, now abandoned. The trenches turn out to contain tripwires, one of which a rat triggers. The ensuing explosion almost kills Schofield, but Blake digs him out and leads him out of the collapsing bunkers. We’ve become so used to the brown and gray of no man’s land that it’s quite a sudden change when the two arrive at some undamaged countryside full of the colour green. An incident involving a burned pilot provides quite a shock which some viewers may have trouble adjusting to, then it’s on to a bombed-out village, Ecoust-Saint-Mein. The Devonshire Regiment is near a wood far down a river, but can they be reached in time before so many men are sent to their deaths? There’s a nicely understated encounter with a French woman and a baby [not hers but she’s looking after it] which may seem cliched but which struck me as a highly likely scenario, especially as any sexual element is avoided. But elsewhere the film struggles just a little after that beginning half hour, with familiar situations and a few heroic moments that seem rather out of place considering the more sober approach elsewhere. I wonder if we’d have had moments like a couple of heroic dashes [on the second one, surely the person doing it would have been crushed or shot within seconds?] if Mendes hadn’t just made two James Bond films? I certainly didn’t not enjoy such moments, and they’re certainly well staged, but Mendes can’t quite settle on how he wants to depict warfare. The time aspect doesn’t seem fully thought through either. At the beginning of the film, things appear to be happening in real time, but this is lost as the movie progresses. The ‘shot’ is not lost, but time has clearly moved along farther than what we’re seeing. If not, then not much actual terrain is covered, and there’s no reason a larger group couldn’t have easily done this instead of giving it to just two guys.

Realistic detail is certainly all over the place, sometimes very quick, like the glancing shots of soldiers as ‘we’ walk through the trenches; the subdued, even apathetic looks seem very believable and will stick in the mind. Also very haunting is when a portion of a river is found to be basically a huge graveyard. Here, we really do get a sense of hell on earth, as we also do in the high point of Roger Deakins’s photography in the film, when ‘we’ awaken to a night sky illuminated by a raging inferno, with flares racing overhead so that the shadows of the surrounding ruins are moving about, virtually dancing. It’s a wonderfully vivid, scary moment. Elsewhere though, Deakins seems a little too reigned in by the long take method to give us lots of his usual visual brilliance, even if one cannot help but admire the technique. I’m sure it was hard to achieve, but I reckon it was still much easier to carry out than in, say, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, where, to give the impression of the entire film comprising of a single take, the walls of the set were on rollers and had to be silently be moved out of the way to make way for the camera and then replaced when they were to come back into shot, and people had to constantly had to move the furniture and other props out of the way of the large camera and then ensure they were replaced in the correct location, while a team of soundmen and camera operators had to keep the camera and microphones in constant motion – as the performers kept to a carefully choreographed set of cues! The question is whether the filming style detracts from the action or overly dominates it. I would say that it doesn’t, though without it the film would seem a lot more average.

Saying that, the performances by George Mackay and Dean Chapman’s performances are fairly strong, particularly Chapman’s, the actor showing a real knack for restrained emotion. He genuinely looks shell shocked for some of the time, virtually operating on automatic. Andrew Scott, Mark Strong, Richard Madden and Benedict Cumberbatch are checkpoints along the way, but they all make a strong impression with the few lines they’re given. Cumberbatch’s character initially seems rather unsympathetic, rude and with a distinct blood lust, until you realise that here’s a person who keeps getting different orders from headquarters and therefore continually has to alter his perspective on sending his men into battle. There’s also a tremendous music score by Mendes’s usual composer Thomas Newman, ranging from ambient background to orchestral dramatics to quiet piano. It might be the best one he’s ever written. And music plays a large part in the film’s most beautiful scene, where a soldier is singing the song ‘Wayfaring Stranger’ as a crowd of other soldiers surround him in awe. I was reminded of that incredibly poignant scene at the close of Paths of Glory, where rowdy American soldiers at a tavern quiet down as they watch a frightened German woman sing a German folk-song. But 1917 rarely reaches those heights again, though it’s never actively poor;. after ll, it’s probably impossible for Mendes to make a poor movie. But overall it doesn’t come close to his best work, and by that I’m not talking about his two Bond movies, fun as they are [though I don’t think they’re top grade Bond movies], but Road To Perdition and Revolutionary Road, two films which seem to me to be borderline flawless, with every element precisely tuned. But it’s still quite an cinematic experience, one that will lose a great deal if viewed at home, and Mendes should be commended for trying to give us something with such a fresh visual approach.

Rating:

Be the first to comment